Translate this page into:

Effectiveness of the Certificate Course in Essentials of Palliative Care Program on the Knowledge in Palliative Care among the Participants: A Cross-sectional Interventional Study

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Palliative medicine is an upcoming new specialty aimed at relieving suffering, improving quality of life and comfort care. There are many challenges and barriers in providing palliative care to our patients. The major challenge is lack of knowledge, attitude and skills among health-care providers.

Objectives:

Evaluate the effectiveness of the certificate course in essentials of palliative care (CCEPC) program on the knowledge in palliative care among the participants.

Subjects and Methods:

All participants (n = 29) of the CCEPC at All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Delhi, giving consent for pretest and posttest were recruited in the study. This educational lecture of 15 h was presented to all the participants following pretest and participants were given same set of questionnaire to be filled as postintervention test.

Results:

In pretest, 7/29 (24.1%) had good knowledge which improved to 24/29 (82.8%) after the program. In pretest, 62.1% had average knowledge and only 13.8% had poor knowledge. There was also improvement in communication skills, symptom management, breaking bad news, and pain assessment after completion of the program.

Conclusion:

The CCEPC is an effective program and improving the knowledge level about palliative care among the participants. The participants should implement this knowledge and the skills in their day-to-day practice to improve the quality of life of patients.

Keywords

Knowledge

palliative care

quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care is recognized as a specialty aimed at relieving suffering, improving quality of life and comfort care. Knowledge in palliative care and end of life care are essential components that is to be learned as a basic training during residency itself. Most of the patient's death in hospital setup occurs not because of an acute event but because of chronic illnesses. Palliative care is needed not only in cancer but also in chronic debilitating diseases.

There are many challenges and barriers in providing palliative care to our patients. The major challenge is lack of knowledge, attitude, and skills among the health-care providers. It is often seen that the pain during end of life is not adequately managed, and patients are not being prognosticated adequately by the physicians.[12] The reason being the lack of training in undergraduate as well as postgraduate teaching curriculum and lack of sensitization among the policymakers. Hence, health-care professionals should have an adequate knowledge of palliative care to implement the knowledge in medical setup.

Indian Association of Palliative Care (IAPC) is an organization under which all the palliative care activities and program in India are being run. It was established in 1994 in collaboration with WHO and Government of India with the goal of promoting and propagating the concept of palliative care all over the country. IAPC is concerned with the palliative care awareness, educational programs, drug procurement policies, and drug availability in different parts of the country.

The certificate course in essentials of palliative care (CCEPC) under IAPC had been started in 2007 as an initiative to enhance knowledge and create interest in palliative care among the participants. The target group are health-care professionals and nurses. It is a basic course being floated all over the country in several batches. The main aim of this course is to popularize the palliative care in India and to have an adequate numbers of trained palliative care professionals. This course is an Indian replica of a similar type of course that is being conducted in the UK and Nepal under Princess Alice Hospice, UK by Dr. Max Watson. Doctors with MBBS or BDS degree and Nurses with Diploma/Bsc Nursing can apply for this program. The fees for this course is Rs. 2000 for doctors and Rs. 1500 for nurses including training fee, examination fee, and the course material.

This course is being conducted in 30 centers of India. In Delhi, this course is being offered at only one center – Department of Anaesthesiology and Pain and Palliative Care, Room number-242, second floor, Dr B. R. A. Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital (IRCH), All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi-110029. Other centers in India are situated at Mumbai, Bangalore, Kerala, Mangalore, Chandigarh, Thrissur, Tamil Nadu, Chennai, Mysuru, Guwahati, Cuttack, Jaipur, Kolkata, Hyderabad, Indore, Ahmedabad, Lucknow, Lalitpur, Jalandhar, Bhubaneshwar, and Dehradun.

They also provide IAPC handbook on palliative care and materials for case reflection guidance. It is a distance educational program with 15 h of lecture sessions, 8 weeks of distant learning at home through distance education, and 10 days of clinical learning. Its main aim is to make participants learn basic principles of palliative care, improve communication skills, manage common symptoms, and deal with end of life issues.

It is accomplished in two parts – Part A and Part B. Part A comprises of 2 days lecture program and submission of a case reflection on patients requiring palliative care followed by theory and spotting examination 1 month later. For completing Part A, candidates need to pass in their theory examination as well as in the reflective case history. The examination consists of short answer questions, true or false, fill in the blank, multiple choice questions (MCQ), and spotting. Those who do not clear the examination in the first attempt are given one more chance to appear in the examination without charging any extra fees. Course curriculum includes following topics:

-

Introduction to palliative care

-

Communication skills

-

Spirituality, ethics in medical practice, and psychological issues

-

Management of pain and other symptoms

-

Nursing issues in palliative care

-

Palliative care in HIV/AIDS

-

Care of the elderly and pediatric palliative care

-

Palliative care emergencies

-

End of life care

-

Communication workshop

-

Palliative care intervention

-

Managing breathless patients in palliative care

-

Managing gastrointestinal symptoms

-

Intervention beyond ladder

-

Lymphedema Management

-

Ethical issues in oncology care

-

Balancing nutrition in palliative care.

Second part include 10 days training at any recognized palliative care center authorized by IAPC in India within 1 year of clearing the theory examination. Part B is optional, and after 10 days of clinical posting, candidates are required to submit a logbook attested by the head of the palliative care center. Successful completion of both the parts will allow the participants to apply for the procurement and dispense of oral morphine under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act.

CCEPC was started in AIIMS in June 2008. Since then, it is being conducted twice a year in the month of June and November. Around, 447 doctors and nurses have been trained till now in palliative care and have completed Part A of CCEPC from this center with around 30 participants per batch. However, only, 24 participants have completed Part B in IRCH, AIIMS till now.

To analyze the impact of the CCEPC on the level of knowledge in palliative care and to evaluate the magnitude of the knowledge, we have conducted this study among the delegates who had participated in this course on June 10 and 11, 2017 at Dr. BRA IRCH, AIIMS, New Delhi. Improving knowledge of palliative care will improve the quality of palliative care in the country.

No studies have been done till now evaluating the effect on knowledge in palliative care among participants with completion of CCEPC. The present interventional cross-sectional study evaluated the effect of the CCEPC on the knowledge in palliative care among the participants. Budding residents and nursing staffs in their learning phase can play an important role by learning and implementing palliative care in their day-to-day clinical practice as they are the ones who spend most of the time with the patients.

Aims and objectives

The primary outcome of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the CCEPC program on the knowledge in palliative care among the participants and to evaluate the level of knowledge among them.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Design of study

This cross-sectional interventional study was undertaken in the Department of Onco-Anaesthesia and Palliative Medicine at Dr. BRA, IRCH, AIIMS, Delhi. An approval was taken from the Institutional Ethics and Research Committee of AIIMS Hospital, New Delhi, India.

Subjects

All participants of the CCEPC of any age of either gender giving consent for pre- and post-test were recruited in the study.

Setting

This program of educational lecture was presented to all the participants following pretest in the seminar room of the hospital. After completion of all the lectures, participants were given same set of questionnaire to be filled as postintervention test.

Methodology

All participants were given self-administered, structured pro forma to be filled in a fixed format including details of their qualification, demographic data, their field of work, their training in palliative care and (30) MCQ covering all the aspects of the palliative care. It consisted of questions based on the topics covered in the program.

The participants completed posttest assessment of palliative care knowledge following 15 h of organized educational intervention over 2 days. Pretest was conducted before the start of the program, and the delegates were not allowed to keep any copy of the pretest and answers were not discussed. The residents were given 20 min to complete the test. Posttest was administered immediately after the completion of the course.

Knowledge on palliative care was assessed by 30 questions on relevant topics, and each question had 4 multiple choice options with a single correct answer. Each correct answer were given score of 1 and score of 0 for an incorrect answer. The total scores were calculated by arithmetic sum of all the correct answers with maximum score of 30. The knowledge based on scores were graded as follows: >20 = good knowledge, 15–20 = fair/average knowledge, and < 15 = poor knowledge.

The participation of the delegates in this study was on voluntary basis, and an informed written consent was taken.

Validity of the study

The questionnaire was revised and validated by 5 medical professionals from different health field.

Statistical analysis

The data were entered into Microsoft excel chart and results were interpreted accordingly.

OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS

A total of 38 delegates had registered for this program, out of which 35 had actually participated. One participant had not given pretest, and 5 had not given posttest. Hence, out of 35, 6 participants were excluded from the study (82.8% response rate) and results were interpreted from 29 participants.

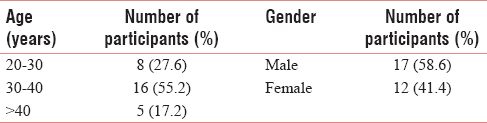

Most of the participants were in the age group of 30–40 years with the mean age of 34.38 years. Male to female ratio was 17:12 [Table 1].

Only 3 nurses participated in this program and rest of all the participants were doctors out of which 44.8% were anesthetists [Tables 2, 3, and Figure 1] Only 3 delegates had prior training in palliative care [Table 4].

- Qualification of participants (n = 29).

In pretest, 7/29 (24.1%) had good knowledge which improved to 24/29 (82.8%) after the program. In pretest, 62.1% had average knowledge and only 13.8% had poor knowledge, and in posttest, none of the participants were having poor knowledge [Table 5 and Figure 2]. Mean score of participants increased from 61.6% to 79.6% after CCEPC program.[Table 6] Good knowledge was comparable in both the gender. However, males had better average knowledge as compared to females [Table 7]. Doctors had better knowledge in pretest as compared to nurses [Table 8].

- Impact of certificate course in essentials of palliative care on the knowledge level in palliative care among the participants (n = 29).

Pretest revealed 34.5% participants with confidence in communication skills which improved to 93.1% with posttest. In pretest, only 17.2% were comfortable in symptom management which increased to 82.8% after posttest. About 82.8% participants became comfortable in breaking bad news after the communication workshop post-CCEPC. Nearly, 86.2% became familiar with the pain scales after completion of the program [Table 9 and Figure 3].

- Impact of certificate course in essentials of palliative care on communication skills, pain assessment, symptom management, and delivering bad news (n = 29).

DISCUSSION

This cross-sectional interventional study was carried out at IRCH, AIIMS on June 10 and 11, 2017. Lectures and seminars have been the basis of medical education in India for years. Knowledge and skills acquired through these lectures are being measured by viva and MCQs. Similarly, we wanted to evaluate the effectiveness of CCEPC through MCQs.

We recruited 29 participants in the study. Most of the participants were in the age group of 30–40 years. About 58.6% of respondents were male and 41.4% were female. Only 3 nurses participated in this program and rest of all the participants were doctors out of which 44.8% were anesthetists.

This study revealed that 86.2% participants had average-to-good knowledge in pretest. There was 58.7% improvement in good knowledge with 15 h of lecture program. This may be due to the fact that the candidates interested in learning palliative care had enrolled for the program. Similar improvement in knowledge ranging from 10% to 40% have been reported by various authors after lecture sessions, home visits, presentations, case discussions, hospice rotation, online educational programs, and workshops.[345678910111213]

In 2004, Williamson concluded 23% improvement in knowledge in palliative medicine with 4 days, 32 h curriculum among 3rd year medical students. The curriculum included lecture sessions, home visits, presentations, and case discussions.[3]

In 2005, Charles et al. demonstrated 10% improvement in knowledge after 4 weeks of curriculum among internal medicine residents. The curriculum included hospice rotation and palliative care program.[4]

In 2010, Koczwara et al. conducted study to evaluate the effect of 7.5 h online educational program on palliative oncology on knowledge level in health-care providers. Out of 90 participants, 91% were satisfied in terms of knowledge and 75% were of opinion to change their practices.[14]

In 2015, Karger et al. in Germany evaluated effectiveness of 1-week seminar in palliative care among 31 undergraduate medical students and found to have significant increased knowledge in postseminar test.[15]

However, few authors have also reported no significant improvement in knowledge and attitudes toward palliative care following an educational intervention.[1617]

In pretest, only 13.8% participants had poor knowledge which decreased to 0% in posttest. Similarly, in 2016, Nnadi and Singh concluded that palliative care knowledge was poor in 22.5% of the total 49 medical interns due to ignorance which decreased to 4.1% during posttest.[7]

Fischer et al. concluded that the predictors of the good knowledge were prior experiences and training in palliative care.[16] In our study too, those with prior training in palliative care had average-to-good knowledge.

Part A of CCEPC has been designed to enhance theoretical knowledge while Part B is implicated to enhance clinical knowledge. In our center, only 24 participants out of total 447 have successfully completed Part B. Practical training is important for clinical implications. More and more participants should be encouraged to complete Part B to apply palliative care knowledge practically.

Health-care professionals experiences many challenges and difficulties in various palliative care domains such as communication, pain and other symptom management, explaining death, and prognosticating families or caregivers.[18] Good communication skills form the core element of the palliative care. It is major determinant of both patients satisfaction as well as physician confidence.[19] Conversations must have empathy, honesty, and compassion in physicians while dealing with end of life care, prognosticating, talking about death, and breaking bad news.

In this study, pretest revealed 34.5% participants were confident in communication skills which improved to 93.1% with posttest. In pretest, only 17.2% were comfortable in symptom management which increased to 82.8% after posttest.

Similarly, in 2011, Pelayo et al. evaluated the effect of an online palliative care educational model on knowledge, satisfaction, and attitude among 85 primary care physicians in Spain. There was an improved confidence in symptom management and communication in interventional group as compared to control group.[5]

In 2011, Valsangkar et al. evaluated knowledge among 106 medical interns regarding palliative care in people with HIV/AIDS and effect of structured intervention in the form of course curriculum and workshops on knowledge dimensions. The structured intervention resulted in better application of palliative care in terms of symptoms management and dealing with psychosocial needs.[6]

Kizawa et al. found moderate improvement in knowledge levels among physicians after a regional palliative care program. The physicians also showed improved skills in communication and pain management.[20]

Harrison et al. reported 9% improvement in communication skills in posttest among 43 military medical residents after 1 week of hospice and palliative medicine rotation.[21]

In 2017, Inoue et al. evaluated the effect of PEACE program (Palliative care Emphasis program on Symptom Management and Assessment for Continuous Medical Education) among 923 lung cancer specialist which was started in Japan in 2008. They found improved knowledge, better symptomatic treatment, and better communication skills in those who participated in this program.[22]

In medical field, doctors show various kinds of avoidance strategies with respect to breaking bad news and fear of death and thus affects quality of medical practice.[2324] Thus, it is important to change the attitude of medical professionals involved in palliative and end of life care. About 82.8% participants became comfortable in breaking bad news after the communication workshop post-CCEPC. Parikh et al. evaluated the effect of training in communication skills with respect to palliative care among 69 3rd year medical students. They concluded that 80% residents had retained skills of giving bad news and 45% were comfortable explaining about death and dying after 1 year of training.[25]

In our study, 86.2% became familiar with the pain scales after completion of the program. Similar to our findings, Glasheen et al. in 2006 found that 25 physicians became more comfortable and confident in pain and symptom management and dealing with ethical issues after 2 days of educational intervention.[10] Irwin et al. also showed an increased knowledge in pain assessment and management among 30 psychiatry residents following 32–144 h of rotation in hospice and palliative care.[26]

Only 3 (10.3) nurses participated in this program. Several studies have shown that palliative care educational programs are effective in improving nurses attitude, confidence, and knowledge.[272829] In this study, 66.6% nurses had poor knowledge and 33.3% had average knowledge in pretest. There were different findings in a study by Das et al. (2015) where 20% of the staff nurses had adequate knowledge, 69% were having moderate knowledge, and 11% were having poor knowledge regarding palliative care.[30] Although nursing issues in palliative care and communication workshop was part of the course content, some more different curriculum separate for nurses could have also been included in the program.

Palliative care requires multidisciplinary approach and is concerned with improving quality of life in patients with advanced incurable terminal diseases. With a shift of the curve from infectious diseases to lifestyle and noncommunicable diseases, medical services also need to be trained in palliative care rather than cure. Unfortunately, medical discipline in India focuses on cure rather than comfort care. Palliative care in developing countries like India is still not a very popular specialty because of ill-defined training or program and poor perks.

In India, palliative care is taught neither at undergraduate and nor at postgraduate level. One approach to improve palliative care may be the education of doctors and nurses through various palliative care programs, training and certificate courses in palliative care. Palliative care training can be given in various ways – face-to-face lecture sessions, case presentations, demonstrations, group discussions, role plays, online courses, bedside teaching, experiential opportunities, and simulation. These training programs aim at improving clinical practices, attitudes, skills, and knowledge in palliative care and should be evaluated regularly for its effectiveness and impact on clinical outcomes.

Limitation

Most of the participants were postgraduate, so knowledge gap was not assessed among undergraduates. Moreover, doctors and nurses were clubbed together in this study. The study also did not reflect knowledge of medical professionals from all the branches as mostly anesthetists had enrolled in this program and only those interested had attended this program. Educational intervention too was for brief period only. There was no control group and number of participants were also less in our study. Sample size is too small to conclude any findings and such trial can be conducted at all the centers where this course is being provided. There was very short duration between pretest and posttest. Thus, long-term outcome of the program in clinical practice was not evaluated. Learned skills such as communication or breaking bad news could not be evaluated practically.

CONCLUSION

This study concluded that the CCEPC is an effective program and it improves knowledge level about palliative care among the participants. The participants should implement this knowledge and skills in their day-to-day practice to improve the quality of life in patients requiring palliative care.

Recommendation

Palliative care should be included in curriculum as basic course in undergraduate and postgraduate levels as suggested by WHO.[15] More and more palliative educational programs to be organized all over the country to spread awareness and to improve knowledge, attitude, and skills of health-care professionals. This course should be evaluated regularly, and the feedback from this study should encourage those who are involved in these programs. At each point of contact, participants should be encouraged to complete Part B of CCEPC. As this course is conducted all over the country, multicentric study of this trial can help in revising national guidelines pertaining to palliative care programs.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge IAPC and examination coordinator Dr Lullu Mathew for starting this wonderful initiative. We also would like to thank all the participants of CCEPC and the faculties involved in conduct of the program for giving their time and support and making this program successful.

REFERENCES

- Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Report from the Institute of Medicine Committee on Care at the End of Life. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1997.

- [Google Scholar]

- A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT principal investigators. JAMA. 1995;274:1591-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improving knowledge in palliative medicine with a required hospice rotation for third-year medical students. Acad Med. 2004;79:777-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence of improved knowledge and skills after an elective rotation in a hospice and palliative care program for internal medicine residents. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2005;22:195-203.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of online palliative care training on knowledge, attitude and satisfaction of primary care physicians. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of knowledge among interns in a medical college regarding palliative care in people living with HIV/AIDS and the impact of a structured intervention. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17:6-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge of palliative care among medical interns in a tertiary health institution in Northwestern Nigeria. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:343-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Management of pain in terminally ill patients: Physician reports of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;15:27-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Survey of palliative care concepts among medical students and interns in Austria: A comparison of the old and the new curriculum of the medical university of Vienna. Palliat Care. 2008;2:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Effect of an Intensive Palliative Care-Focused Retreat on Hospitalist Faculty and Resident Palliative Care Knowledge and Comfort/Confidence [abstract] 2006. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 1 http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/the-effect-of-an-intensive-palliative-carefocused-retreat-on-hospitalist-faculty-and-resident-palliative-care-knowledge-and-comfortconfidence/

- [Google Scholar]

- A required third-year medical student palliative care curriculum impacts knowledge and attitudes. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:784-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary care residents improve knowledge, skills, attitudes, and practice after a clinical curriculum with a hospice. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017;34:713-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of geriatric and palliative medicine education on the knowledge and attitudes of internal medicine residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:143-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reaching further with online education? The development of an effective online program in palliative oncology. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25:317-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Pilot study on undergraduate palliative care education – A study on changes in knowledge, attitudes and self-perception. J Palliat Care Med. 2015;5:236.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care education: An intervention to improve medical residents’ knowledge and attitudes. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:391-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Introduction of palliative care into undergraduate medical and nursing education in India; A critical education. Indian J Palliat Care. 2004;10:55-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Obstacles to the delivery of primary palliative care as perceived by GPs. Palliat Med. 2007;21:697-703.

- [Google Scholar]

- Elephant in the room project: Improving caring efficacy through effective and compassionate communication with palliative care patients. Medsurg Nurs. 2010;19:101-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improvements in physicians’ knowledge, difficulties, and self-reported practice after a regional palliative care program. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50:232-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- A hospice rotation for military medical residents: A Mixed methods, multi-perspective program evaluation. J Palliat Med. 2016;19:542-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of nationwide palliative care education program on lung cancer specialists. J Clin Oncol 2017:35. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.e21715

- [Google Scholar]

- "It's not that easy" – Medical students’ fears and barriers in end-of-life communication. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30:333-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Personal fear of death and dying affects the proper process of breaking bad news. Arch Med Sci. 2013;9:127-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of palliative care training and skills retention by medical students. J Surg Res. 2017;211:172-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatry resident education in palliative care: Opportunities, desired training, and outcomes of a targeted educational intervention. Psychosomatics. 2011;52:530-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of a nursing education program about caring for patients in japan with malignant pleural mesothelioma on nurses’ knowledge, difficulties and attitude: A randomized control trial. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34:1087-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of palliative care education on nurses’ knowledge, attitude and experience regarding care of chronically ill children. J Nat Sci Res. 2013;3:Epub ahead of print.

- [Google Scholar]

- A palliative care link nurse programme in Mulago Hospital, Uganda: An evaluation using mixed methods. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and attitude of staff nurses regarding palliative care. Int J Sci Res. 2015;4:1790-4.

- [Google Scholar]