Translate this page into:

Spiritual Needs and Quality of Life of Patients with Cancer

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background and Aim:

Information about spiritual needs and quality of life (QoL) is limited in Iranian cancer patients. This study was conducted to determine the relationship between spiritual needs and QoL among cancer patients in Iran.

Methods:

This correlational study included a convenience sample of 150 eligible cancer patients who were hospitalized in the oncology wards and outpatient clinics. Using two questionnaires; the spiritual needs survey and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QoL Questionnaire-C30 data were collected. The data were analyzed by SPSS software version 19.

Results:

Our findings showed that the total mean score of spiritual needs was (64.32 ± 22.22). Among the categories, the lowest score belonged to “morality and ethics” component (2.18 ± 1.64), and the highest score belonged to “positivity/gratitude/hope/peace” component (15.95 ± 5.47). The mean score of QoL was (79.28 ± 19.20). Among the categories, the lowest score belonged to “global health status” component (8.44 ± 3.64), and the highest score belonged to “functional” component (36.57 ± 10.28). Pearson correlation coefficient showed that spiritual needs score positively correlated with QoL (r = 0.22; P = 0.006).

Conclusion:

The results of the present study suggest that information about the relationship between spiritual needs and QoL in patients with cancer. It should be improve QoL to meet spiritual need of these patients. In addition, the continuous and in-service education of cancer patients and nurses who work with them can be helpful in this area.

Keywords

Cancer patients

Iran

Quality of life

Spiritual needs

INTRODUCTION

Being diagnosed and living with a life-threatening illness such as cancer is a stressful event that may profoundly affect multiple aspects of an individual's life.[1] Cancer is a major public health problem in the United States and many other parts of the world. It is currently the second leading cause of death in the United States and is expected to surpass heart diseases as the leading cause of death in the next few years.[234]

In Iran, cancer is the third common cause of death after cardiovascular and traumatic events. In addition, more than 30,000 of Iranian people died because of cancer, and more than 80,000 new cases are added to this figure annually.[56] Cancer can significantly increase patient's spiritual needs. Policy, research, and practical guidelines for health-care professionals now routinely suggest that spiritual needs are an essential component of holistic health-care assessment.[78]

The World Health Organization has stressed the spirituality, and religious dimensions of patients' lives need to be an integral part of the patient management.[9]

Assessing the spiritual needs of patients is difficult. This difficulty arises in part from the ambiguity and complexity of the concept of spirituality, especially with respect to differentiating between the concepts of religion and assessing spirituality in people who are not religious.[10] In addition, because of a wide range of belief systems and religious practices some difficulties in defining spiritual needs, but definitions are necessary to help a shared conceptual understanding.[11] Spiritual needs are concerned with the “spirit” aspect of the human condition.[1213]

Spiritual needs are defined as needs and expectations which humans have to find meaning, purpose, and value in their life, such needs can be specifically religious, but even people who have no religious faith or are not the members of an organized religion have belief systems that give their lives meaning and purpose.[11]

Patients' spiritual needs fell into several dimensions. The most commonly recognized domain was the need to finding meaning and purpose in life. The need for love, peace, belonging/connectedness, and forgiveness were also quite common.[10]

According to Hampton et al.,[14] spiritual needs, spiritual distress, and spiritual well-being of patients with terminal illnesses can affect their quality of life (QoL).[14] Arrey et al.[9] also claimed that spiritual needs related to patients' disease can affect their mental health and failure to meet these needs may impact their QoL.[9] The QoL has become an important concept in cancer care.[15] QoL is a multidimensional construct of an individual's subjective assessment of the impact of an illness or treatment on his/her physical, psychological, social and somatic functioning, and general well-being.[16] It has been shown that assessing QoL in cancer patients could contribute to improve treatment and could be an important prognostic factor.[15] A number of previous studies have examined spirituality, religious beliefs, and QoL in patients with cancer.[512]

Nixon et al.[12] investigated the spiritual needs of neuro-oncology patients from a nurse perspective in the UK. The authors identified patients' spiritual needs as need to talk about spiritual concerns, showing sensitivity to patients' emotions, responding to religious needs. Participants appeared largely to be in tune with their patients' spiritual needs and reported that they recognized effective strategies to meet their patients' and relatives' spiritual needs. Their findings also suggest that nurses do not always feel prepared to offer spiritual support for neuro-oncology patients.[12]

Hampton et al.[14] assessed the spiritual needs of patients with advanced cancer who were newly admitted to hospice home care. They found that great variability in spiritual needs. Being with family was the most frequently cited need (80%), and 50% cited prayer as frequently or always a need. The most frequently cited unmet need was attending religious services. They suggest the importance of a focus on the spiritual more than the religious in providing care to patients at the end of life.[14]

In Iran, Hatamipour et al.[5] in a qualitative study explored the spiritual needs of cancer patients. Using purposive sampling method, 18 cancer patients who referred to the Cancer Institute of Imam Khomeini Hospital in Tehran were selected, and their spiritual needs emerged out of the conventional content analysis of interviews conducted with them. Four themes including “connection,” “seeking peace,” “meaning/purpose,” and “transcendence” emerged as spiritual needs.[5]

Zeighamy and Sadeghi[17] explored the spiritual/religious needs of adolescents with cancer in Iran.

Purposeful sampling method was used. Fourteen adolescents with cancer and their families and six nurses were interviewed. To analyze the data, qualitative content analysis was used. From the data analysis, four main themes emerged: The need for a relationship with God; the need for a relationship with the self; the need for a relationship with others; and the need for a relationship with the environment and nature.[17]

Mansano-Schlosser and Ceolim[18] conducted a cross-sectional descriptive study to evaluate the QoL in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy in Brazil. They used the WHO QoL brief instrument, during the period from April to June of 2008. Comparison between domain scores showed the psychological domain reached the highest scores and the social domain reached the lowest scores.[18]

Vallurupalli et al.[19] in a cross-sectional study assessed the role of spirituality and religious coping in the QoL of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative radiation therapy. Totally, 69 patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative radiotherapy were selected. Scripted interviews assessed patient spirituality, religiousness, religious coping, QoL, and perceptions of the importance of attention to spiritual needs by health providers. The result showed that patient spirituality and religious coping were associated with improved QoL. Most patients considered attention to spiritual concerns an important part of cancer care by physicians (87%) and nurses (85%).[19]

Winkelman et al.[20] examined the relationship between spiritual concerns and QoL in patients with advanced cancer. Totally, 69 cancer patients receiving palliative radiotherapy were recruited. They found that total spiritual struggles, spiritual seeking, and spiritual concerns were each associated with worse psychological QoL.[20]

Bai et al.[21] explored the relationship between spiritual well-being and QoL among patients newly diagnosed with advanced cancer. Spiritual well-being was measured using the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy–spiritual well-being scale; QoL was measured with the functional assessment of cancer therapy. They concluded that spiritual well-being was associated with QoL.[21]

According to ethical codes of most countries, health professionals are expected to provide care on the basis of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs and status of patients, and play an active role in meeting their spiritual needs and promoting QoL.[12]

The continuing growth in the population of cancer patients in Iran has prompted nurses and researchers to develop nursing interventions that promote patient QoL. Cancer patients' spiritual needs and its association with QoL have not yet been well identified in Iran. Recognizing spiritual needs and QoL of patients with cancer is considered a vital element in providing spiritual and cultural care; therefore, it is necessary to obtain a better understanding of nature of spiritual needs and QoL in Iranian patients.

Different findings between Islam, Christian, and secular societies, reiterates the need for more research to be done among Muslim communities.[22] In addition, the results of research on spiritual needs among cancer patients from diverse cultures and religions are not applicable in other cultures and faiths, including Iranian-Islamic culture. Thus, the present study aimed to investigate the relationship between spiritual needs and QoL among Iranian cancer patients.

METHODS

Design

This cross-sectional, correlational study aimed to examine the relationship between spiritual needs and QoL of patients with cancer.

Sampling and setting

The sample size was estimated 150 cancer patients by using a pilot study, by considering the standard deviation of 25.2 for QoL in cancer patients (α = 0.05, d = 0.4) using the following formula:

Sample selected through convenience sampling method. Therefore, all patients were not offered the opportunity to participate. The inclusion criteria were diagnosed with cancer at least for 6 months, age 18 and above, able to communicate, and hospitalized in oncology ward at least 2 weeks. Exclusion criteria were having a chronic disease (other than cancer), psychiatric problems, and using psychological drugs.

Instrument

Background information

A questionnaire was designed to obtain background information that was assumed to influence spiritual needs and QoL. The questionnaire was developed based on three categories: Demographic characteristics such as gender, age and marital status, job, income, education, and questions regarding religion, and religious practice.

Spiritual need survey

The spiritual need questionnaire was developed by Galek et al.[23] This comprehensive survey provides direction for health-care professionals interested in a more holistic approach to patient well-being. This scale has 29-items grouped into 7 subscales. The seven dimensions – and a brief description of the some of the items measuring them – are as follows: (1) Meaning and purpose – need to find meaning in life, meaning in suffering, and why this happened to me; (2) love and belonging – need to give and receive love, feel companionship and connected to the world, and be accepted as a person; (3) hope, peace, and gratitude – need to feel hopeful, thankful, grateful, and a sense of peace; (4) religion and divine guidance – need to pray, for religious worship/rituals, and guidance from a higher power; (5) death concerns and resolution – need to address concerns about death and forgive and be forgiven; (6) appreciation of art, and beauty – need to appreciate or experience music, art and beauty; and (7) morality – need to live a moral and ethical life. Each construct was comprised of 3–6 items, except for morality, which was measured by a single-test item.[23]

The validity and reliability of the scales were rechecked in the Iranian context. Ten faculty members at the Kerman University of Medical Sciences reviewed the content of the scales. They agreed that the scale was appropriate. To reassess the reliability of the translated scale, alpha coefficient of internal consistency was computed. The alpha coefficient for spiritual needs scale was 0.98, so the translated scale presented acceptable reliability and validity.

Quality of life questionnaire

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QoL Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ)-C30 was developed by the EORTC QoL Group. It has been translated and validated in over 100 languages and is used in more than 3000 studies worldwide. It is supplemented by disease-specific modules, for example, breast, lung, head and neck, esophageal, ovarian, gastric, cervical cancer, multiple myeloma, esophagogastric, prostate, colorectal liver metastases, colorectal, and brain cancer which are distributed by the EORTC QoL department. The questionnaire items focus on evaluating general health, physical, emotional, and social aspects. It comprises 30 questions grouped into the 5 functional scales. The questionnaire also includes 3 symptomatic scales – fatigue, nausea, and pain – as well as 6 single questions evaluating the intensity of the following symptoms: dyspnea, sleeplessness, lack of appetite, constipation, diarrhea, and financial problems. The last two questions deal with the overall health assessment. There is a four-degree scale in the answers to the questions in the questionnaire (never 1, sometimes 2, often 3, very often 4).[24]

All of the scales and single-item measures range in score from 0 to 100. A high-scale score represents a higher response level. Thus, a high score for a functional scale represents a high/healthy level of functioning; a high score for the global health status/QoL represents a high QoL, but a high score for a symptom scale/item represents a high level of symptomatology/problems. The total scores of QoL range from 0 to 100; a higher score represents a higher (“better”) level of functioning or a higher (“worse”) level of symptoms.[25] In Iran, Montazeri et al.[26] assessed validity and reliability of this scale. it has suitable validity, and the alpha Cronbach's coefficient was reported 0.92.[26]

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the social sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) version 18. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied, to assess the data from a population with a normal distribution. The data were analyzed by descriptive statistics and Student's t- test or one-way ANOVA and Pearson correlation coefficient. The results were of significance with a level of 0.05.

Ethical consideration

Oral informed consent was obtained from each participant. The confidentiality of patients was respected by removing all identifying elements. This study approved by the Ethics Committees of the Kerman University of Medical Sciences (Approval number: 463/93/k). The researchers explained voluntary participation, the guarantee of anonymity, freedom to withdraw from participation.

RESULTS

Participants

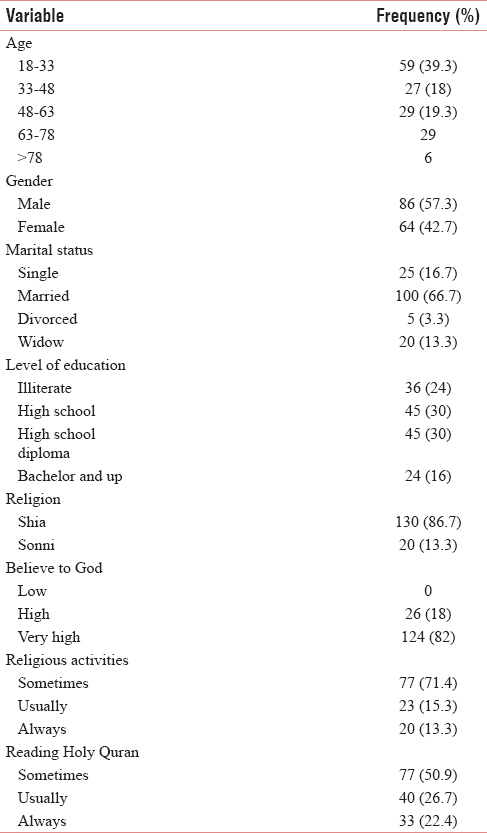

A descriptive analysis of the background and clinical information revealed that the participants was aged 18 – >78 years, with a mean age (44.88 ± 19.5). A total of 57.3% of participants were male, and 66.7% were married; most of them (30%) had high school diploma. About 6.7% of the participants were Shia Muslim. The majority of participants (82%) stated that they had a high level of belief in God. Most of them (50.9%) stated that they sometimes read Holy Quran. The majority of patients (71.4%) claimed that they sometimes performed religious activities [Table 1].

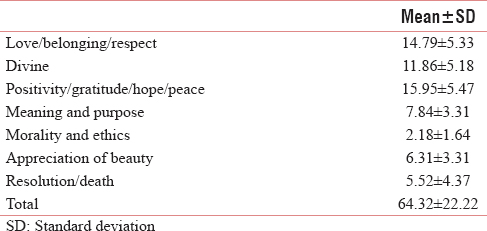

Spiritual needs

Table 2 shows the total mean score of spiritual needs and dimensions. The mean total score of spiritual needs was 64.32. Among dimension of spiritual needs, the highest mean score belonged to the domain of “positivity/gratitude/hope/peace.” The lowest mean score belonged to the domain of “morality and ethics” [Table 2].

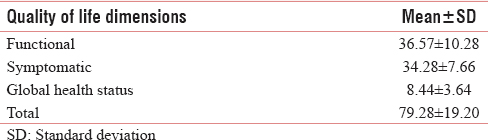

Quality of life dimensions

Table 3 shows the total mean score of QoL and dimensions. The mean total score of QoL was 79.28. Among dimensions of QoL, the highest mean score belonged to the domain of “functional.” The lowest mean score belonged to the domain of “global health status” [Table 3].

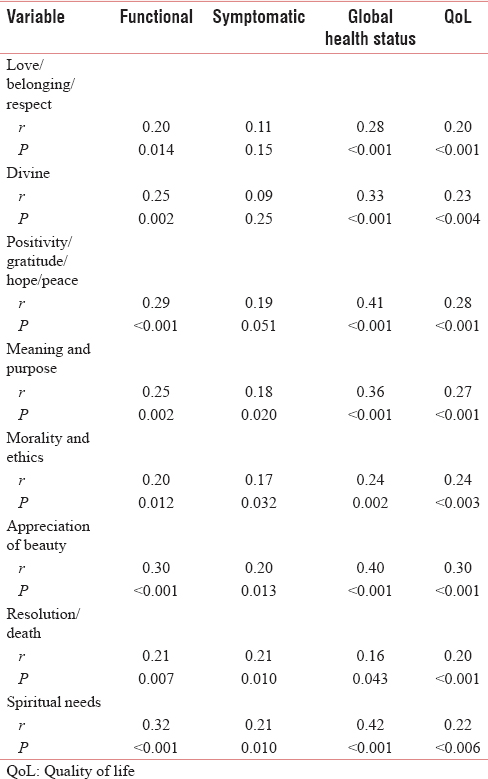

Correlations between spiritual needs and quality of life

Pearson correlation coefficient showed that significant correlation between spiritual needs and QoL. Spiritual needs were significantly correlated with all the dimensions of QoL. In addition, QoL had a significant association with all dimensions of spiritual needs [Table 4].

Correlations between spiritual needs with demographic information

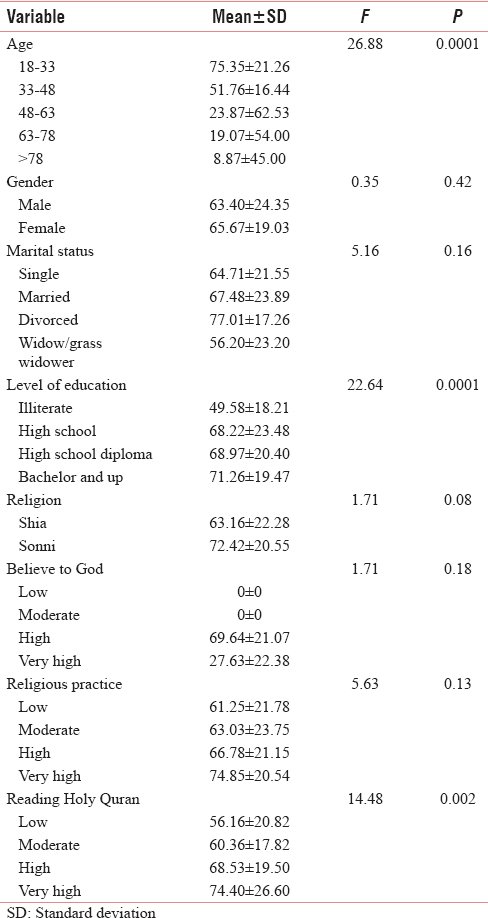

One-way ANOVA revealed a correlation between patients' age, the level of education, and reading Holy Quran with spiritual needs score. This means patients who were older (P = 0.001), had a higher level of education (P = 0.001) and read Holy Quran (P = 0.001) are more likely to experience spiritual needs (P = 0.002). However, there was no significant relationship between spiritual needs and other demographic information [Table 5].

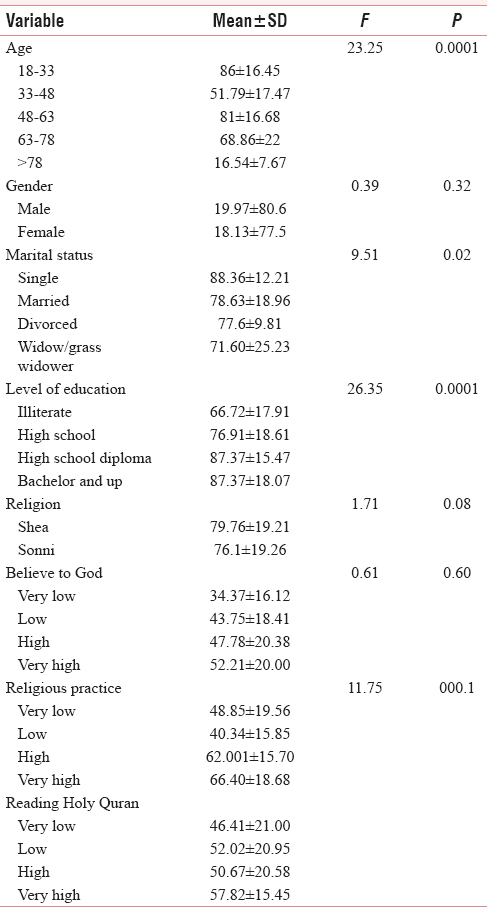

Correlations between quality of life with demographic information

One-way ANOVA revealed a correlation between patients' age, marital status, and level of education with the QoL score. This means patients who were older (P = 0.001), single (P = 0.02) and had a higher level of education (P = 0.001) are more likely to experience a better QoL. However, there was no significant relationship between QoL and other demographic information [Table 6].

DISCUSSION

This is the first study that evaluated the relationship between spiritual needs and QoL in Iranian patients with cancer. Our results demonstrated that cancer patients have several spiritual needs. Among dimensions of spiritual needs, the highest mean score belonged to the domain of “positivity/gratitude/hope/peace” and the lowest mean score belonged to the domain of “morality and ethics.

Hampton et al.[14] found that great variability in spiritual needs of patients with advanced cancer. Being with family was the most frequently cited need (80%), and 50% cited prayer as frequently or always a need. The most frequently cited unmet need was attending religious services.[14] Winkelman et al.[20] reported that the most common spiritual struggle items were “wondering why God has allowed this to happen” and “wondering whether God has abandoned me.” The most common spiritual-seeking items were “seeking a closer connection to God” and “thinking about what gives meaning to life.”[20]

Vilalta et al.[27] concluded that two spiritual needs emerged as the most relevant for the patients with advanced cancer: Their need to be recognized as a person until the end of their life and their need to know the truth about their illness.[27] In Iran, Hatamipour et al.[5] showed that prayer and communication with God are a part of spiritual needs. Yousefi and Abedi[28] concluded that formation of mutual relation with patient, encouraging the patient, and providing the necessary conditions for patient's connection with God, namely, spiritual need of hospitalized patients.[28]

In general, spiritual needs are among an individual's essential needs in all places and times,[28] but oncology patients are likely to reflect on spiritual and existential issues due to the uncertainty of their future.[12] In the present study, positivity/gratitude/hope/peace” was the most frequently cited need and “Morality and ethics” was the lowest frequently cited need.

Differences between spiritual needs in above studies can be due to; spiritual and religious beliefs are individual and vary between people. Spiritual needs consist of more than religious worship and are highly individual for each patient[29] and the spiritual needs of a patient in a concrete moment can be influenced by his or her physical, psychological, social well-being, and by emotions.[27]

Within the psychology literature, numerous emotions have been labeled as faith-based emotions. These include emotions such as gratitude, compassion, empathy, humility, contentment, love, adoration, reverence, awe, elevation, hope, forgiveness, tolerance, loving-kindness, responsibility, contrition, joy, peace, trust, duty, obligation, and protectiveness.[30]

Positive emotions experienced in relation to God, such gratitude has been conceptualized as a moral emotion that involves the perception of intentional benevolence from another. It is valued and promoted by the major world religions, and empirical links have been observed between gratitude and measures of religion and spirituality. Feeling grateful to God was associated with higher levels of positive affect, happiness, and life satisfaction.[31]

Overall, our study found that the mean total score of QoL was 79.28. The highest mean score belonged to the domain of “functional” and the lowest mean score belonged to the domain of “global health status.” Kim and Kwon[1] indicated that QoL score for global health status was 46.34. The highest QoL score on the functional scale was for cognitive functioning, followed by role functioning, emotional functioning, physical functioning, and social functioning. The highest QoL score on the symptoms scale was fatigue, followed by appetite loss, constipation, nausea and vomiting, insomnia, pain, and financial difficulties.[1]

Färkkilä et al.[32] explored end-stage breast, prostate and colorectal cancer patients' health-related QoL and showed patients close to death had lower health-related QoL scores.[32]

In Iran, Dehkordi et al.[33] investigated the QoL in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. They found that the QoL was fairly favorable in the majority (66%) of the patients.[33]

It is important to highlight that each individual has a particular way of operationalizing his or her evaluation of the QoL, and the evaluation of one same subject can vary with time, with the variation of priorities along life and with the circumstances through which life can change.[18]

Physical, psychosocial, and spiritual discomforts experienced by patients with cancer occur alongside other confrontations, and the endless struggle during the disease decreases the QoL. Although studies over the years show no consensus on the concept of QoL by its inherent subjectivity of individual perceptions, a multicenter project involving different cultures highlighted three aspects of great relevance to the QoL construct: The subjectivity of the human being, who is enhanced by thoughts, feelings, and emotions that compose one's internal world, inherent in each human being; the multidimensionality of QoL, which includes the dimensions of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual order that bring significant repercussions; and the bipolarity caused by positive and negative influences that permeate peoples' daily lives.[34]

Our data also support the hypotheses; there was a significant association between spiritual needs and QoL of patients with cancer. This finding consistent with the previous studies.[20193521] Vallurupalli et al.[19] assessed the role of spirituality and religious coping in the QoL of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative radiation Therapy. They concluded that most participants (84%) indicated reliance on religiousness and/or spirituality beliefs to cope with cancer. Patient spirituality and religious coping were positively associated with improved QoL.[19] Teichmann et al.[35] found that the QoL significantly correlated with spirituality score. In addition, spirituality was related to all QoL domains. Their findings suggest that spirituality occupies an important place in the person's perception of their QoL in a changing socioeconomic environment as the one in Estonia.[35] Bai et al.[21] found that spiritual well-being was associated with QoL.[21] Winkelman et al.[20] showed that spiritual concerns are associated with poorer QoL among advanced cancer patients. In addition, total spiritual struggles, spiritual seeking, and spiritual concerns were associated with worse psychological QoL.[20] According to Freire et al.,[34] physical, psychosocial, and spiritual discomforts experienced by patients with cancer decreases their QoL and deserving health professionals' attention.[34] The effect of spirituality, as the main factor, on different aspects of life in creating life expectancy, increasing the compatibility, coping with suffers from incurable diseases, and existential crisis resulted from life-threatening diseases can be understood. In Eastern Societies, people have rich religious and ancient cultural beliefs. Therefore, it seems that in these societies, paying attention to the spirituals is an desirable way to improve the QoL and compatibility with threatening physical disabilities.[36]

Based on the findings, patients who were older are more likely to experience spiritual needs.

It could be due to, older people tend to have high rates of involvement in religious and/or spiritual endeavors and it is possible that population aging will be associated with increasing the prevalence of religious and spiritual activity.[37]

Winkelman et al.[20] showed that younger age was associated with a greater burden of spiritual concerns. Findings of their study suggested that spiritual concerns have important associations with advanced cancer patient QoL, in particular for younger patients. This study also demonstrates that most patients consider attention to spiritual concerns to be an important part of cancer care, with greater spirituality or religiousness being the strongest predictors of patients' desires for health-care professionals to consider their spiritual concerns in the advanced cancer setting.[20]

According to the results, patients who single and had a higher level of education are more likely to experience a better QoL. Üstündağ and Zencirci[4] found that singles had worse psychological and general well-being. They also reported no relationship existed between education level and life quality.[4] Mansano-Schlosser and Ceolim[18] found that the scores obtained in the domains of WHO QoL - Brief and the score of overall QoL showed no significant correlation with age. The physical domain scores showed a trend to the difference between the diverse educational levels, being lower for the illiterate.[18] In Iran, Dehkordi et al.[33] showed that there was no correlation between the QoL and variables such as age, sex, marital status, duration of disease, economic conditions, and occupational function. Furthermore, no correlation was found between the QoL and the patients' educational level.[33]

One interpretation is that patients with less education, even in an equal access to health-care system, may experience greater difficulty understanding educational material on the disease, its treatments, and post treatment care. Poor understanding of the self-care instructions provided in the clinical setting or poor understanding of information on the kinds of post treatment support available to manage symptoms may contribute to difficulties with the management of symptoms, worry about disease burden and recurrence, and difficulty in adjusting one's lifestyle to treatment schedules and symptoms.[38]

Limitation

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. The study sample is small and nonrandomized and since a convenient sampling method was used, the results should not be generalized to apply to the spiritual needs and QoL of all cancer patients. In addition, this is a cross-sectional study which has limitations in establishing the prospective causal effects of spiritual needs on QoL. In the future, a prospective longitudinal study with a larger sample size is needed in this area.

Recommendations for future studies include studies with a larger sample size so that the data can be generalized across a broader population, qualitative studies to gain insight into cancer patients' spiritual needs.

CONCLUSION

Spiritual needs have been shown to be correlated with the QOL. It provides the patient with an endogenous source of well-being and strength. Improvement in spiritual support is suggested as a strategy to enhance the QoL for patients with cancer. In addition, spiritual needs to become part of every nursing curriculum, and nurses should be offered continuing education that will enable them to better support patients with cancer.

Research implication includes the call for professionals to meet the spiritual needs of Muslim cancer patients and incorporating religious components in their treatment, especially in oncology wards.

It is important that spiritual needs are addressed in health care as the current study indicates that patients do have spiritual needs and healthcare professionals should be addressing spiritual needs.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Comfort and quality of life of cancer patients. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2007;1:125-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting the quality of life of cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: A questionnaire study. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2015;2:17-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spiritual needs of cancer patients: A qualitative study. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:61-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- INCCCP 2013. Iranian National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/ncccp/index.htm

- [Google Scholar]

- Spiritual Care in Nursing Principles, Values and Skills. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. :117-34.

- An online survey of nurses' perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1757-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spirituality/Religiosity: A cultural and psychological resource among sub-saharan african migrant women with HIV/AIDS in belgium. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159488.

- [Google Scholar]

- The relative prevalence of various spiritual needs. Scott J Healthc Chaplain. 2006;9:25-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploring the spiritual needs of people dying of lung cancer or heart failure: A prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers. Palliat Med. 2004;18:39-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- An investigation into the spiritual needs of neuro-oncology patients from a nurse perspective. BMC Nurs. 2013;12:2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spiritual Care: Being in Doing. University of Malta, Malta: Preca Library; 2010.

- Spiritual needs of persons with advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2007;24:42-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life in arab women with breast cancer: A review of the literature. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Head and neck cancer: Closer look at patients quality of life. J Cancer Ther. 2016;7:121.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life of cancer patients during the chemotherapy period. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2012;21:600-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of spirituality and religious coping in the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative radiation therapy. J Support Oncol. 2012;10:81-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The relationship of spiritual concerns to the quality of life of advanced cancer patients: Preliminary findings. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:1022-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploring the relationship between spiritual well-being and quality of life among patients newly diagnosed with advanced cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13:927-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- I can't pray' – The spiritual needs of Malaysian Muslim patients suffering from depression. Int Med J Malaysia. 2016;15:103-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessing a patient's spiritual needs: A comprehensive instrument. Holist Nurs Pract. 2005;19:62-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The EORTC core quality of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30): Validity and reliability when analysed with patients treated with palliative radiotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:2260-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Brussels 2001

- [Google Scholar]

- The European organization for research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Support Care Cancer. 1999;7:400-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of spiritual needs of patients with advanced cancer in a palliative care unit. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:592-600.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spirituality 1: Should spiritual and religious beliefs be part of patient care? Nurs Times. 2010;106:14-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Religion, Spirituality, and Positive Psychology: Understanding the Psychological Fruits of Faith. ABC-CLIO: Santa Clara University; 2012.

- The role of religion and spirituality in positive psychology interventions. American Psychological Association, Editors: Kenneth I. Pargament 2013:481-508.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health-related quality of life among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer patients with end-stage disease. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1387-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Oman Med J. 2009;24:204-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health-related quality of life among patients with advanced cancer: An integrative review. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2014;48:357-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- The relationship between spiritual health and quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. Islam Lifestyle Cent Health. 2012;1:17-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spirituality, religiosity, aging and health in global perspective: A review. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:373-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Education predicts quality of life among men with prostate cancer cared for in the department of veterans affairs: A longitudinal quality of life analysis from caPSURE. Cancer. 2007;109:1769-76.

- [Google Scholar]