Translate this page into:

Signs of Spiritual Distress and its Implications for Practice in Indian Palliative Care

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

Given the particularity of spirituality in the Indian context, models and tools for spiritual care that have been developed in Western countries may not be applicable to Indian palliative care patients. Therefore, we intended to describe the most common signs of spiritual distress in Indian palliative care patients, assess differences between male and female participants, and formulate contextually appropriate recommendations for spiritual care based on this data.

Methods:

Data from 300 adult cancer patients who had completed a questionnaire with 36 spirituality items were analyzed. We calculated frequencies and percentages, and we compared responses of male and female participants using Chi-squared tests.

Results:

Most participants believed in God or a higher power who somehow supports them. Signs of potential spiritual distress were evident in the participants’ strong agreement with existential explanations of suffering that directly or indirectly put the blame for the illness on the patient, the persistence of the “Why me?” question, and feelings of unfairness and anger. Women were more likely to consider illness their fate, be worried about the future of their children or spouse and be angry about what was happening to them. They were less likely than men to blame themselves for their illness. The observations on spirituality enabled us to formulate recommendations for spiritual history taking in Indian palliative care.

Conclusion:

Our recommendations may help clinicians to provide appropriate spiritual care based on the latest evidence on spirituality in Indian palliative care. Unfortunately, this evidence is limited and more research is required.

Keywords

India

palliative care

spiritual distress

spiritual trust

spirituality

INTRODUCTION

In palliative care literature, there exists large agreement that spiritual care is an essential component of good palliative care. This consensus is based on empirical studies that have shown that spirituality, which can include religious aspects, influences the ways in which patients experience disease at the end of life.[1234] It is also commonly agreed that spirituality has to be addressed by the entire palliative care team. Consequently, physicians, and nurses, too, should at least have the capability to recognize signs of spiritual distress, because that will allow them to be able to refer patients to professionals with more advanced knowledge and training in spirituality if required.[56]

However, clinicians often find it hard to provide spiritual care to patients with advanced disease, or even just screen them for potential spiritual issues. Several barriers to the provision of spiritual care have been identified in the literature. Lack of time is often cited as a major reason for not addressing spiritual issues and concerns.[78910] It cannot be denied that clinicians are sometimes overburdened with work, and they may indeed have no time to address nonphysical symptoms of disease. Yet, lack of time may also serve as a convenient excuse for not having to tread an area in which some clinicians do not feel entirely conversant. They may, for instance, feel uncertain what precisely constitutes spirituality.[711] If clinicians have doubts regarding the meaning of spirituality, they may also wonder what vocabulary they should use to discuss spiritual issues and concerns with patients. Because of their own insecurity about the subject, they may prefer not to talk about it.[710] Physicians and nurses may then feel tempted to think that the provision of spirituality is the sole responsibility of other professionals, in particular chaplains.[712] Concrete talking about spirituality is sometimes further complicated by the power imbalance that exists between clinicians and patients, due to which the former may consider inquiring about spirituality as an inappropriate intrusion into the patient's private life.[12] However well-intended such a consideration of power inequality may be, it will most often just mask an overall lack of skills in spiritual care provision.[8] This lack of skills indicates that spirituality has received insufficient attention in healthcare practitioners’ education.[79101112]

In palliative care in India, such barriers to the provision of spiritual care are exacerbated by the particularity of spirituality in the Indian context.[13] This peculiarity complicates spiritual care provision and education in Indian palliative care because most approaches to spirituality have been developed in Western countries, notably the US and the UK.[14] Therefore, they may not be applicable to the Indian palliative care context and should be applied with great caution. The problem is that, at present, there are no tools or guidelines on spirituality specifically designed for Indian palliative care. Thus, there is a clear need for research that can inform spiritual care practice and education in palliative care in India. One of the issues that such research should consider is potential differences between Indian men and women in their experience of spirituality. In an earlier study, it was found that female palliative care patients in India are more likely to be spiritually distressed than men.[15] However, the meaning and significance of this observation within the Indian palliative care context and the clinical implications still need further exploration.

The aim of the current study was 2-fold. First, we intended to describe the most common signs of spiritual distress in Indian palliative care patients so that clinicians would be able to recognize them when they encounter them in their palliative care practice. As part of that aim, we planned to explore gender differences in spirituality. Second, on the basis of all these observations, we wanted to formulate concrete recommendations to empower palliative care professionals and volunteers in India to more efficiently address spiritual distress. We anticipated that these recommendations could also be included in future education on spirituality in Indian palliative care to make efforts by palliative care educators in this field more attuned to the specific Indian context.

METHODS

For this study, we used data that had been collected while developing a new questionnaire for the study of spirituality in Indian palliative care. The development of this questionnaire and the data collecting process have been described elsewhere.[16] The questionnaire was administered to 300 adult patients undergoing treatment at the pain clinic of a tertiary cancer hospital in New Delhi, from September to December 2014. The study had been approved by the Ethics Committee (Institutional Review Board) of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (New Delhi) where the study was conducted.

The questionnaire contained 36 spirituality items, which were developed after an extensive systematic review of the literature on spirituality in Indian palliative care.[13] A psychometric assessment of the questionnaire showed that it is a good instrument for the study of spirituality among palliative care patients in India. The questionnaire consists of four meaningful factors or dimensions: shifting moral and religious values (factor 1), support from religious relationship (factor 2), existential blame (factor 3), and spiritual trust (factor 4). The alphas for all the factors were found to be within the range of acceptable internal consistency.[16]

As we explained in a previous study, we focused on transcendence in our operationalization of spirituality because the literature review had shown that this focus was culturally appropriate.[16] Since the survey's aim was the assessment of signs of spiritual distress, predominantly, the items dealt with negative feelings, such as feeling lonely, the experience of guilt, fear of the future, and loss of purpose. However, there were also eight items that explicitly focused on positive feelings, including the experience of support from a higher power, feeling at peace, and gratefulness. Because these items dealt with feelings of support and peace, agreement with these items could be interpreted as an expression of spiritual trust. It was assumed that people in spiritual distress would score negatively on these items. Participants were asked to indicate their agreement with each of the items on a 3-point Likert scale (agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree).

When the data collection process was over, all data were entered into a Microsoft Office 2013 Excel file. This file was then imported in IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (Amonk NY, USA). We used this program to calculate frequencies and percentages and assess associations between gender and agreement with the spirituality items using Pearson's Chi-square tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A nearly equal number of male (n = 152, 50.7%) and female (n = 148, 49.3%) patients were included in the study. The sample was predominantly Hindu (80.3%, n = 241).

Table 1 describes the participants’ agreement with the eight items that connoted positive spiritual feelings. The fact that for all but one of these items agreement hovered around 80% shows that a large majority of the participants believes in God or a higher power who somehow supports them. They also feel better or experience peace while trying to connect with this transcendent reality through prayer, chanting, or pūjā. Chi-square tests revealed no statistically significant differences between male and female respondents in these eight items.

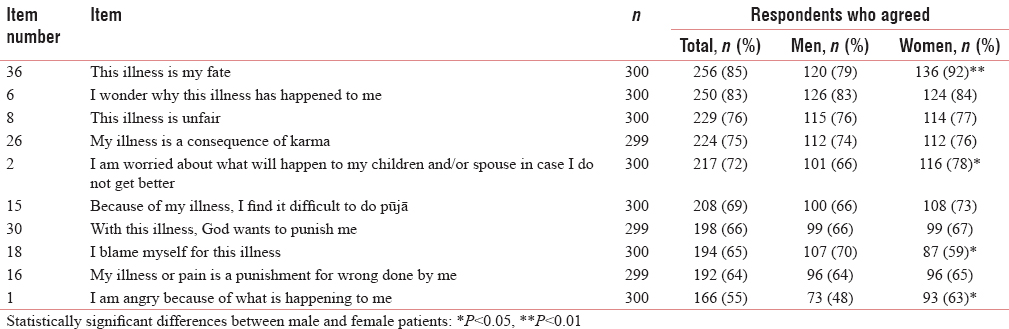

The large agreement on these positive spiritual items notwithstanding, there was also much support for items that could indicate potential spiritual distress. In Table 2, we have listed the ten items that found most agreement among the participants besides the eight positive spiritual items that have been analyzed above. These items can be seen as the most common signs of potential spiritual distress. We compared the responses of men and women to these ten items using Chi-square tests.

The responses show a strong agreement with existential explanations of suffering that directly or indirectly put the blame for the illness on the patient. This is shown by the agreement on statements that probed after self-blame (64.7%), belief in karma (74.9%), and illness as punishment (66.2% and 64.2% in two slightly different statements). At the same time, patients kept wondering why the illness had happened to them (83.3%), felt that the illness was unfair (76.3%), and experienced anger because of what was happening to them (55.3%).

Chi-square tests revealed statistically significant differences between men and women in their responses to four aspects of spiritual distress. Women were more likely to consider illness their fate, be worried about the future of their children or spouse and be angry about what was happening to them. They were less likely than men to blame themselves for their illness.

DISCUSSION

The observed gender differences in signs of spiritual trust and distress add to the scientific evidence of the existence of differences pertaining to spirituality between male and female patients in palliative care and cancer care. Several studies have indeed pointed toward such differences.[15171819] However, the evidence is equivocal, and not all studies have confirmed this gender difference.[2021] Therefore, our observations regarding gender differences require further analysis because they do have limitations. While assessing the differences between men and women, we did not correct for multiple comparisons, or raise the level of significance, to avoid that relevant associations would remain undetected. Hence, it remains possible that the observed differences between male and female participants are due to chance. To counter this argument, we could add that a meaningful picture emerges from the comparisons between male and female participants. Overall, women were more likely to see illness as (undeserved) fate that befalls them, but for which they are not to blame. This explains why they felt more anger than men, who were more likely to blame themselves for the disease, and for that reason, may have considered anger pointless. The fact that women were more worried about the future of their spouse or children is also no surprise when we consider that in Indian society women most often have the role of carer in the family. Women may fear that their family will be bereft of care after their death. As interesting as these hypotheses may be, they remain, in a sense, preliminary until we have more evidence supporting these gender differences in spirituality among Indian palliative care patients. Until we have that evidence, it will remain hard to formulate strong recommendations for a differential clinical approach to spirituality in women as compared to men in palliative care in India.

We did not observe statistically significant differences between men and women in the eight positive spirituality statements. This is indicative of an equally strong belief in God among male and female respondents. The large agreement with the eight positive statements seems to somehow contrast with the very profound and common signs of spiritual distress that were observed in the other items. The large agreement with items of both spiritual trust and spiritual distress seems to indicate that most persons receiving palliative care have both signs of spiritual distress as well as spiritual trust. This observation triggers the question as to what extent the respondents were actually truthful when they responded to the positive statements. It would not be unreasonable to assume that there is a social desirability bias in these answers, as in Indian society, belief in God who supports his or her devotees is the norm.[22] Likewise, many Indian palliative care patients are convinced that God can and will cure their illness,[2324] and in a study conducted among 100 patients admitted to an inpatient palliative care unit in India, 98% testified to believe in God.[25] Possibly, these patients as well as the participants in the current study may have felt that they had to conform to this societally expected belief in God, notwithstanding their spiritual struggle since the onset of their disease.

Although it is definitely possible that at least some respondents agreed with the eight statements because they considered such answers socially desirable, we should not discard the patients’ genuine longing for spiritual peace and divine support, even if the patients may feel frustrated because God's intervention in their disease process does not seem to be imminent. Moreover, the most common signs of potential spiritual distress, which we described in Table 2, do not directly contradict the patients’ belief in a God or higher power that supports them. For instance, patients who are convinced that their illness is a consequence of a bad deed done in the past, for which they are now experiencing suffering as a karmic effect or divine punishment, can still legitimately believe that in the end, God will help them to overcome the disease as soon as they have atoned for their sins. We should also not forget that terminally ill patients are in an extremely difficult phase in their lives where they can experience contradictory emotions. We also see this in the answers of the respondents. Large agreement with existential explanations of suffering, such as belief in karma, fate, and the view of illness as a punishment for sin, did not prevent 76.3% of the participants to nevertheless find their illness unfair, and 83.3% kept wondering why the illness had happened to them. Notwithstanding the myriad answers that Indian spirituality and religion offer to that issue, Indian palliative care patients have been found to continue asking that question.[2627] Profound spiritual suffering may ensue when, in the patient's experience, items of spiritual trust are trumped in frequency and intensity by items of spiritual distress, which include feelings of dissatisfaction with interpretations and ideas that give meaning to suffering.

This point illustrates that spiritual issues always need to be assessed within the broader context of the patients’ lives and their experience of their illness. This is precisely what is done in spiritual history taking. In this process, the patients are enabled to express their values, beliefs, and sources of meaning, and it becomes possible to assess to what extent the illness impacts spiritual well-being.[28] Taking such a spiritual history can be a challenge in palliative care patients in India because much of the literature on spiritual history taking as well as available tools focus on Western patients. As a consequence, some of the questions and vocabulary that are suggested to use in the process of spiritual history taking may actually be hard to grasp for palliative care patients in India. Particularly, concepts such as spirituality, faith, and belief, for which there is no unambiguous equivalent in Indian languages, may confuse patients. However, on the basis of the observations of the current study, which revealed common signs of spiritual distress, we can offer concrete recommendations that may facilitate spiritual history taking.

To initiate the dialogue about spiritual issues, the clinician can ask the patient to tell about the ways in which the illness has changed his or her life, and in particular, whether and how it has impacted the patient's attitude to those things he or she used to consider important in life. This is, of course, an opportunity to discuss those things that give meaning in life. For patients, this could be a job, friends, and family, but also belief in God and religious rituals. For Indian patients, family is of particular relevance. Indian cancer patients have been observed to derive strength from their extended family,[29] and they highly value happiness with family.[30] Above, we already discussed the pervasiveness of belief in God. Religious rituals and practices can be important to connect with God. Therefore, it is no surprise that Indian palliative care patients are very much interested in practices such as pūjā and meditation.[252631]

While exploring these issues, it is essential to let the patient talk without the clinician offering concrete examples, because Indian patients, out of respect for their clinician, may be inclined to answer affirmatively to these suggestions, even if they do not represent their real feelings. At the same time, the clinician should listen carefully to the patient and be attentive for subtle clues that may point to spiritual issues. Our study has shown that Indian palliative care patients will almost invariably respond affirmatively to questions of whether they believe in God and whether that belief gives them strength. Hence, it is very well possible that patients mention their belief in God in the discussion. It can be recommended to ask questions regarding belief in God as it relates to their illness, and the nature of their faith at the beginning of spiritual history taking, because this will show to patients the clinician's openness to the subject and may also lead a few patients to reveal the distress that they experience in their relationship with God. It should be remembered that patients may be angry with God. Issues with religious and spiritual practice may sometimes be indicative of a troubled relationship with God. Indian palliative care patients have been reported to stop praying because they no longer trust God.[32] Talking about such concrete religiosity might help patients to open up to broader spiritual issues. The patient can also be asked whether they wonder why this illness has happened to them. If the patient answers affirmatively, the clinician can ask whether or not the patient has any answers to this “why” question. Our study results indicate that topics such as fate, karma, and illness as punishment for sin could come up here. Other studies, too, confirm the frequent occurrence of these beliefs among palliative care patients in India.[263133]

Obviously, spiritual aspects such as faith in God or belief in karma and fate need not be signs of spiritual distress. They can very well be part of positive coping. Therefore, having identified spiritual issues and concerns that are important to the patient, the clinician should follow up on these and try to find out how essential these are to the patient and whether certain aspects of them cause distress. This can be done by asking specific questions. It may be a good idea to consider asking patients who have said to believe in God whether the illness has affected their interest in hearing or thinking about God. If the patient has expressed belief in karma or fate, the clinician could ask whether the patient frequently ponders about these issues. More generally, the clinician could inquire about the patient's satisfaction with his or her existential answers. If the clinician feels that the patient is actually not satisfied, he or she could ask whether the thought that the illness is unfair occurs often. A patient who has expressed an interest in religious practices such as pūjā, prayer, and chanting could be asked how significant these are to him or her, and whether or not he or she is satisfied with the way in which he or she currently practices them. For various reasons, Indian palliative care patients may find it hard to perform religious and spiritual practices as per their wishes. Reasons may include a general difficulty to relate with God or practical issues such as physical limitations caused by progressing illness or lack of privacy in an inpatient palliative care setting.[3435] The inability to practice religion and spirituality in a way that the patient considers desirable may be a substantial cause of distress.

Throughout this process of spiritual history taking, the healthcare provider may have identified specific spiritual issues and concerns that point to spiritual distress. Now, it is time to attempt to find appropriate channels – persons or organizations – that can help the patient to overcome this distress. To this end, the clinician may ask whether the patient knows people to whom he or she can talk about the identified issues and concerns. In the course of the dialogue, persons outside the palliative care team who can support the patient's spirituality may already have been mentioned. The clinician could discuss how these persons can get involved concretely. The healthcare provider may also ask whether and how the patient would like the palliative care team to support him or her with these problems. A suggestion to talk again about the identified issues and concerns later may reassure patients of the team's continued support in spiritual matters.

Clinicians who intend to apply our suggestions in practice should exert some caution. The recommendations are mainly based on findings from one study in a tertiary cancer hospital with a predominant Hindu population. We can wonder to what extent, findings from the sample can be generalized to other palliative care patients in India, particularly in contexts where Non-Hindu patients constitute a more sizeable part of the patient population. Some of the items in the questionnaire, such as those focusing on pūjā, chanting, and karma, are particularly meaningful for Hindus but may be less effective to assess spiritual trust and distress among patients adhering to other religions. Moreover, in certain palliative care programs, not just the multicultural constellation of the patient population but also that of its staff and leadership may create unique contexts for the assessment of signs of spiritual distress. This may, for instance, be the case in palliative care centers in India that operate from a Christian mission but care for a largely Non-christian patient population. There is an urgent need for multicenter studies on spirituality in Indian palliative care. Such studies could assess the efficacy of the recommendations of this article and should investigate to what extent these recommendations can be fitted into existing spirituality tools. Clinicians should also be aware that spiritual issues and concerns evolve over time in patients. Therefore, spiritual history taking is, in a certain sense, never a completed task. It is always imperative to remain attentive to changes in patients’ spiritual issues and concerns. Sometimes, certain issues and concerns may become less prominent as the disease progresses, while new ones come up. While reassessing patients, our recommendations may be helpful, too.

CONCLUSION

This study has shown that palliative care patients in India may often believe in God or a higher power that supports them, but they also display signs that may indicate spiritual distress. By using the observations from this study, we have formulated recommendations to assess spiritual distress in a socioculturally appropriate manner in Indian palliative care. By applying these recommendations, some of the barriers to the provision of spiritual care to palliative care patients in India may be overcome, as the recommendations empower clinicians to take a spiritual history of these patients with more competence. Whenever a spiritual history is taken in this way, patients will be more satisfied with their care, the relationship between the patient and the palliative care team will improve, and the patient's overall quality of life may increase. Taking such a spiritual history may take some extra time, but it will lead to better patient outcomes.

Financial support and sponsorship

Joris Gielen is a postdoctoral fellow of the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO). This fellowship enabled him to work on this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Jordan Potter, a former graduate assistant at the Center for Healthcare Ethics of Duquesne University, for editing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- “If God wanted me yesterday, I wouldn’t be here today”: Religious and spiritual themes in patients’ experiences of advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:581-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spirituality, quality of life, psychological adjustment in terminal cancer patients in hospice. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2016;25:961-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding what matters most to people with multiple myeloma: A qualitative study of views on quality of life. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:496.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethos, mythos, and thanatos: Spirituality and ethics at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46:447-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- How do Australian palliative care nurses address existential and spiritual concerns? Facilitators, barriers and strategies. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:3197-205.

- [Google Scholar]

- Why is spiritual care infrequent at the end of life? Spiritual care perceptions among patients, nurses, and physicians and the role of training. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:461-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- GPs’ views concerning spirituality and the use of the FICA tool in palliative care in Flanders: A qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:e718-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence-based spiritual care: A literature review. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2012;6:242-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nurse and physician barriers to spiritual care provision at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48:400-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spirituality as an ethical challenge in Indian palliative care: A systematic review. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14:561-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- What can we learn about the spiritual needs of palliative care patients from the research literature? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43:1105-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and nature of spiritual distress among palliative care patients in India. J Relig Health. 2017;56:530-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development and psychometric assessment of a spirituality questionnaire for Indian palliative care patients. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:9-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploring spiritual needs and their associated factors in an urban sample of early and advanced cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2014;23:786-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Demographic and clinical predictors of spirituality in advanced cancer patients: A randomized control study. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:1779-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of spirituality at the end of life. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1720-1.e5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spiritual pain among patients with advanced cancer in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1106-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spiritual well-being among outpatients with cancer receiving concurrent oncologic and palliative care. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:919-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- God in India. Diversiteit en Devotie in de Indische Religies. Tielt: LannooCampus; 2013.

- Punjabi immigrant women's breast cancer stories. J Immigr Minor Health. 2007;9:269-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Life after cancer in India: Coping with side effects and cancer pain. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27:344-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial concerns in patients with advanced cancer: An observational study at regional cancer centre, India. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27:316-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spiritual concerns in hindu cancer patients undergoing palliative care: A qualitative study. Indian J Palliat Care. 2013;19:99-105.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploring the meaning of spiritual care in the Indian context: Findings from a survey and interviews. Prog Palliat Care. 2004;12:221-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of the FICA tool for spiritual assessment. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:163-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Punjabi women's stories of breast cancer symptoms: Gulti (lumps), bumps, and Darad (pain) Cancer Nurs. 2007;30:E36-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- What's important for quality of life to Indians – In relation to cancer. Indian J Palliat Care. 2003;9:62-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coping mechanisms among long-term survivors of breast and cervical cancers in Mumbai, India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2005;6:189-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mapping levels of palliative care development: A global view. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:469-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fighting cancer is half the battle… living life is the other half. J Cancer Res Ther. 2005;1:98-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Concerns and coping strategies in patients with oral cancer: A pilot study. Indian J Surg. 2003;65:496-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care services for Indian migrants in australia: Experiences of the family of terminally ill patients. Indian J Palliat Care. 2009;15:76-83.

- [Google Scholar]