Translate this page into:

Development of the Draft Clinical Guideline on How to Resuscitate Dying Patients in the Iranian Context: A Study Protocol

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

The guidelines can be used as a model to guide the implementation of the best options and a suitable framework for clinical decisions. Even a guideline can largely help in challenging problems such as not to resuscitate with high cultural and value load. The guidelines try to improve the health care quality through reducing the treatment costs and variety of care measures. This study aimed to prepare a draft of clinical guidelines with the main aim of designing and drafting the clinical guideline on resuscitation in dying patients.

Methodology:

After selecting the subject of this guideline, in the first meeting of the team members of drafting the guideline, the guideline scope was determined. Then, the literature review done without time limitation, through searching electronic bibliographic information and internet databases and sites such as Medline, EMBASE, Springer, Blackwell Synergy, Elsevier, Scopus, Cochran Library and also databases including SID, Iran Medex, and Magiran. The experts will be the interviewed, and the interviews are directed content analysis.

Conclusion:

Finally, recommendations will be formed by nominal group technique. This study protocol includes informative information for designing and conducting of health professionals intending to create a direct on qualitative, theoretical, philosophical, spiritual, and moral health aspects.

Keywords

Dying patients

Resuscitate

Study protocol

INTRODUCTION

Qualitative and quantitative development of modern science has led to the prolongation of human life. One of the most important advances in medicine has been the use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) since the 1960s to save human lives that have so far saved thousands from death.[1] Although CPR has helped save lives, but in some cases, it prolongs the process of death, suffering, and pain in patients.[2] Prolongation of the dying process, in addition to bringing the pain and suffering for patients, makes the patient's family and the health care system facing major challenges.[3] Such challenges include the transfer of the patient to the hospital, hospitalization in the Intensive Care Unit, the use of equipment and facilities, intensive care bed occupancy meanwhile in dire need of a bed by other patients, severe emotional trauma to the patient and family, value, legal, moral and religious conflicts, and job burnout of care providers for a patient with a life chance <5%, or in case of returning to life with a lower quality of life.[45] Although some discussions were first raised about the end-of-life care measures and not resuscitate of dying patients in 1976, but accepting the issue lasted many years.[6]

For example, in the United States, over a 5-year period from 1988 to 1992, the proportion of patients who tend to receive limited services and support at the end-of-life increased from 51% to 90%. Currently, in Europe and America, no treatment is begun for more than 90% of dying patients in the Intensive Care Unit (ICUs), or the treatments are being cutoff.[7]

Now, in the US, all hospitals with permission from the Joint Commission on Accreditation of organizations related to health care have considered written and developed policies regarding no resuscitation do-not-resuscitate (DNR).[8] In 1994, with the establishment of Palliative Care Society in Germany, a new view to the order of not reviving the dying patients appeared in the country.[9] Some measures have been carried out in this regard in countries such as South Korea,[10] the UK,[1] India,[7] and even in Muslim countries such as Saudi Arabia.[11] Despite starting the debate in many countries, in many cases, the treatment team refuses to perform or written record of the DNR. They believe that the lack of guidelines and legal support prohibits them from doing so.[12] In this regard, the medical team, especially doctors and nurses believe that having a clear guideline with legal protection can have a significant role in guiding such people and prevent many challenges.[13] The guidelines can be used as a model to guide the implementation of the best options and a suitable framework for clinical decisions, and at the same time as an objective criterion for evaluation of the measures taken.[14] Even a guideline can largely help in challenging problems such as do not resuscitate with high cultural and value load. The guidelines try to improve the health care quality through reducing the treatment costs and variety of care measures.[15] In cases, where a variety of clinical evidence may affect the results of patient care, clinical guidelines can help the health professionals to provide proper and effective care measures. Of course, this does not mean that the guidelines can replace professional judgments. Therefore, clinical guidelines specify the clinical judgment, patient's preferences, and exceptions.[16] The purpose of the guidelines is to get a clear understanding of the decision-making models for all the beneficiaries.[17] Obviously, the development of clinical guidelines based on health care in accordance with each country's culture and religion can effectively help the health care team members in making accurate and appropriate decisions.[18] Today, clinical guidelines provide the best available evidence about the mysteries and dilemmas of health. These guidelines can lead to improved quality of health, reduced unnecessary, and harmful or useless interventions.[16] The countries’ cultural and religious diversity have made it nearly impossible to provide an International and guideline regarding DNR of dying patients.[11] Therefore, each country needs to develop such a guideline due to its own cultural, religious, and legal background in this regard.[19] The presence of relevant clinical guidelines supported by law makes it possible for the patient, family, and the health care team provide a respectful death with dignity for their dying patients.[1] According to the above-mentioned, and based on the experience, the researcher working in ICUs and cancer treatment centers has faced several times with cases in which the health care team makes efforts for resuscitation of patients that will not certainly come back to life. In some cases, the family of the patient request DNR their patient. However, issues such as nondeployed and deployed life and present legal rules raised the question for the researcher that whether a guideline for a respectful death with maintaining human dignity can be formulated for dying patients due to cultural requirements and relying on the ethical, Islamic, and national values associated with maintaining humans dignity and rights, considering that Iran is a multi-ethnic and multi-national country? If the answer is positive, who would be obliged to implement these guidelines Thus, focusing on the key challenges in taking care of dying patients, the researchers decided to prepare a draft of clinical guidelines with the main aim of designing and drafting the clinical guideline on resuscitation in dying patients in this regard. Furthermore, the specific objectives of this proposal are as follows:

-

Identifying, assessment and purification of scientific evidence on how to provide resuscitation to dying patients at national and international levels

-

Aggregation and consensus of interdisciplinary professionals in decision-making on how to in dying patients

-

Setting and matching the draft of guideline in dying patients in accordance with local sensitivities (religious, ethnic, and legal).

METHODOLOGY

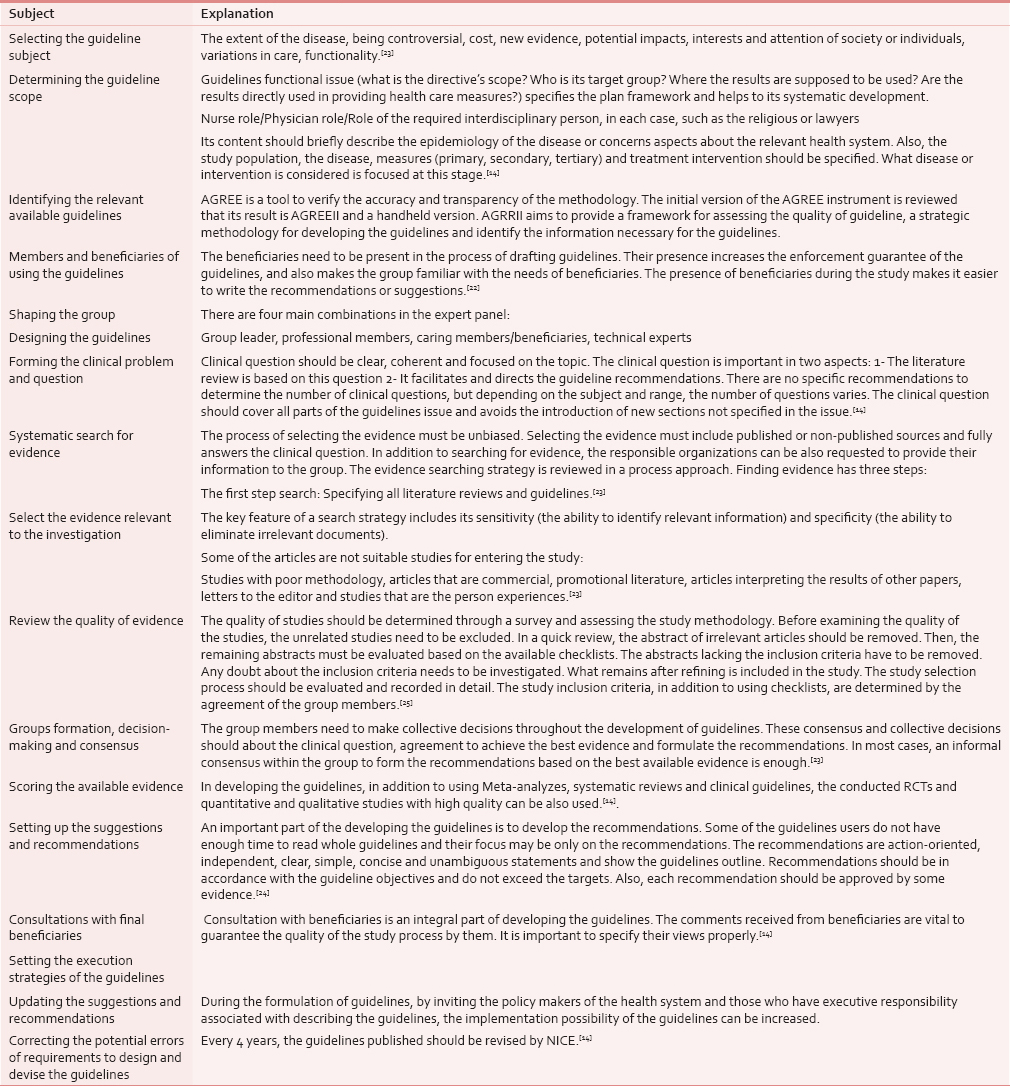

Despite the large number of guidelines, there is no unique and comprehensive approach on how to design a clinical guideline. In reviewing handbooks on developing guidelines, 15 common stages were found [Table 1].[15] But what we realized during developing the clinical manual of resuscitation in patients dying suggests that only with the help of these handbooks, we cannot formulate a comprehensive guideline in all cases, especially in the case of resuscitation and CPR. Therefore, only some of their process and stages can be used. Thus, in formulating the present guideline, the methodology of developing guidelines based on the pragmatism philosophy (Pragmatism is a denial of the idea that the function of thought is to explain, represent, or reflect reality (pragmatists consider thought to be a product of the interaction between human and location) was used and followed.

Set ≠ 1

After selecting the subject of this guideline, in accordance with what is stated above (Relevance of old age, the growing trend of chronic diseases, lack of financial and human resources, imposing huge costs to the patient and society, and diversity in decision-making), Iran is not an exception, and the need to develop a directive in this regard was made in consultation with the team members.

Set ≠ 2

In this study, the scope was primary and before the first session of consensus of “making a decision by the care team on how to resuscitate the dying patients.” In the first meeting of the team members of drafting the guideline, the guideline scope was changed to the decision-making of care and treatment team in specialized and subspecialized hospitals on how to do CPR in patients.

Set ≠ 3

In the development of proposal stage, the beneficiaries of the study were selected as the patient, family, caregivers, and policymakers in the field of the health system and all interdisciplinary and related guidelines.

The study had no time limitation in the literature review and focused on the study guidelines on DNR in the world, which were searched with an emphasis on Islamic and legal principles related to decision making on the DNR. To search for these studies, electronic bibliographic data sources and online databases such as Medline, EMBASE, Springer, Blackwell Synergy, Elsevier, Scopus, Cochran Library as well as databases, including SID, Iran Medex, and Magiran were used. In addition, a manual search was done on articles references. The books on fatāwā (In the Islamic faith is the word for the legal opinion or learned interpretation religious issues) and religious questions from respected Marja’ taqlīdī (Islamic experts in areas of jurisprudence (Fiqh) and Islamic law) – literally means “Source to Imitate/Follow” or “Religious Reference” – were studied trying to study legal issues regarding do not resuscitation of patients.

After preparing the papers, in the first stage, the titles and abstracts of the papers were reviewed, and related items were included in the study. The full text of relevant articles was evaluated and scored with the help of checklist and tables of evidence. To evaluate the quality of each of the articles, the Tool Review related to the design of that article was used. The studies were reviewed with the help of tools such as COREQ and CASP.

Furthermore, no guidelines were found regarding the use of such guidelines at the national level; only three review articles had been written on this subject. At the international level, the full texts of two guidelines were approved and entered in the interview using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation Instrument.

In preparation for the interview, some questions in the same format were extracted after the review; questions such as:

-

Have you ever had a case to consider DNR for?

-

How did you perform? What challenging issues or dilemmas have you experienced? What strategies have you adopted?

-

What credible rules and regulations are available in this regard?

-

What were your standards for considering a DNR?

-

Did you inform the patient and his family?

-

What are the risks and benefits of the DNR?

-

What elements are involved in resuscitation or nonresuscitation of dying patients? Should the consent be taken? Who should complete the consent? At what stage? With what conditions?

Set ≠ 4

Then, the set of texts, review was content analyzed, and seven aspects were extracted accordingly. In accordance with the relevant concept of each of the dimensions, the competent ones or process owners of responsible persons and decision-making were considered. These seven dimensions included the medical team (doctors, nurses), economists, religious, ethics professionals, lawyers, patients, and their families.

In the first phase of the work, as the aim was to draft the guidelines on a theoretical basis, therefore, the seven extracted dimensions were considered. A list of experts competent to meet the conditions (being a clinical specialist in the field, having scientific works such as articles and books on the subject) were considered. Based on priority in each dimension, ten people were selected (however, other than the patient and the family). First, we conducted a deep semi-structured interview with the person with priority (with the help of guiding questions obtained during literature review). If the person was not willing to continue the participation, according to the list, we would interview with the next subject. Furthermore, at the end of the interview, we talked about the extracted dimensions and asked the subjects’ opinions in this regard. Furthermore, at the end of the interviews of the specific dimension, the subjects might have agreed to go to a group or individual or objected the interview with the individuals of another dimension. For example, the social workers and sociologists were included in these dimensions that were added to the study dimensions in interviewing with the experts, while the majority of subjects, especially medical staff were opposed to the patient and family dimension. They suggested that the cultural context of our society is not now able to talk to the families in this regard. For now, this issue is better raised in the community at the beginning through the media, and decisions in this regard would be made in coming years. One of the main challenges in this stage was referring to the adoption of the charter of patients’ rights and the important issue of medical and nursing ethics codes and reports on the process of providing the possible solutions in the work trend. So far, a total of 20 interviews (8 interviews with nurses, 8 by physicians, and 4 interviews with social workers) were carried out. The duration of each interview was 45–60 min, and they were asked to allow audio recording of interviews. At the beginning of each interview, the objectives of the study, the right of individuals to participate or exit from the study at any time of the interview were explained to the participants and informed consent was obtained from them. They were also assured regarding data confidentiality. The author prepared a transcript of the interview text at the end of each interview session and read them several times to reach a deep and accurate understanding of them. Then, the text was analyzed to the smallest meaningful units (codes). The codes were placed in six major categories derived from the literature review.

The permanent and continuous involvement of the subject was used to ensure the credibility and acceptability of data. The codes assessment method by the participants was used. Thus, the initial codes were controlled by the interviewees before classifying in the classes. For coding the codes in the classes extracted, the observer review method (by advisor and consultant professors and two PhD Nursing candidates) was used [Figure 1].

- Diagram of set 3 and 4

More than 1150 codes have been extracted so far from these twenty interviews that were included into each of the seven dimensions based on conducted content analysis, and the analysis continues until data saturation.

The interviews were conducted mostly in the interviewees’ offices. In three cases, the respondents were willing to refer the researcher's office at the School of Nursing and Midwifery. The respondents’ transportation costs were provided, and they were also given a gift.

Regarding the presence of the patient and family, as mentioned, the participants opposed to doing interviews with family members and patients due to cultural issues and Iranian society nonacceptance of such issues. They believed this would depend on the culture-making through by the media, preparation of brochures, banners, etc. However, for providing maximum variation in sampling and with respect to the fact the acceptance or rejection of the DNR order, the patients, and their families have a fundamental role, the team members of guidelines developing decided to do interviews with this group as well.

Set ≠ 5

The final stage of this study, which is ongoing while writing this article, is as follows:

After doing individual interviews and directed content analysis associated with reviewing the literature, the recommendations were extracted. Then, the final recommendations will be extracted with nominal group technique (NGT).

Nominal group technique

In qualitative research to explore the wide range of ideas or deeply examine a specific question among the target population, the group-based method such as NGT is used. In these methods, the depth and richness of the subject are discussed together. Participants in NGT participate in a structured face-to-face meeting lasting at least more than 2 h with a number of people between 5 and 9; however, some researchers may include more people in the group. The key issues used at an NGT meeting include the followings:

-

The question or questions used in the focused group meeting must be clear and motivating so that will lead to a significant participation and presence

-

Participants at the meeting must have expertise in the relevant field or have executive powers

-

The facilitator must be an expert and familiar with the process of the group meetings.[20]

In this approach, we invite at least nine people from those interviewed, those with a more key role or the competent people associated with those having a higher executive capability (heterogeneous). Then, the recommendations extracted during the interviews are discussed. The person's statements are put on a flip chart and also recorded, which will be analyzed in three formats of acceptable, need to be further investigated and irrelevant, and at the end, the final recommendations will be extracted. Two qualitative and quantitative approaches can be used for data analysis. In the qualitative method, the quotations can help to explain individual and group thoughts of people.

In quantitative analysis, the two-stage scoring, Delbecq approach is used. Following voting on the recommendations, at the end of the same session, the final results will be shared.

Regarding the holding place for NGT meeting, we have currently made the requirements to hold the meetings in the corresponding author's office, at the School of Nursing and Midwifery in Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The transportation will be provided by them; a fee for them will be also considered. In this session, the article authors (the core members of the guidelines developers) will attend along with representatives of the interviewees. Furthermore, before entering the NGT meeting, the participants will be asked to declare any conflicts of their interest [Figure 2].

- Diagram of study

Ensuring the reliability of the findings

To ensure the reliability of data derived from interviews with experts, in addition to control them during the meeting, the data will be checked through e-mail with the experts as well. During the development of guideline process, the Conference on Guideline Standardization checklist is also used. The mentioned checklist has 18 items that are particularly used to validate the clinical guidelines, which will be used after writing the drafts of the guideline recommendations.[21]

The participants were assured about the confidentiality of information discussed during the formal and informal interviews. Personal information, political and religious beliefs, and ethnic issues of participants will remain confidential by the researcher. The possibility to announce they are willing to discontinue in participation at any stage of the study is reminding the participants. Article and guideline inclusion criteria are listed in Table 2.

In drafting guideline, at the beginning of the development program of the guideline, all those in the central core or are technical experts, professional members, and the beneficiaries, need to express any conflicts of their interest honestly.[22]

A NICE guide on ethical considerations in the formulation of guidelines believes that the guidelines should be developed in such a way that is bound by the following four basic principles:

-

Respect for autonomy (everyone in the community meetings and focus groups has the right to freely express his opinion. During the facilitating sessions of the group, the issue that all the group members express their opinions and not being affected by one or more people who have a higher power should be considered. Furthermore, the guidelines should be developed in such a way that people can freely accept or reject the health care and providing services to improve the health. The concept of patient choice needs to be considered in the guidelines)

-

Nonmaleficence (Lack of physical and mental harm must be met during the drafting of guidelines. The guideline recommendations should be developed in a way that the minimum harm affects the patient)

-

Beneficence (It is closely related to the principle of nonmaleficence. The NICE Committee believes that the recommendations should be written in a way the patient is minimally hurt)

-

Justice (Mismatch between demands and resources in providing health care can lead to injustice. NICE insists that the guidelines should be developed in such a way that justice is met in distribution of services based on the relevant guidelines).[14]

CONCLUSIONS

Clinical guidelines are often developed and formulated sentences that help the physicians and other health care team members in making appropriate decisions. The use of some guidelines to develop them can be helpful. However, based on this study, one can conclude that the handbooks available in the field of medical issues, which are dependent on the context and culture of each country, cannot be helpful alone. Therefore, in this study, we used the 5-step method that we extracted during the work. There is no strong evidence in this approach to use. However, the agreement of the experts’ opinions forms the major basis of the work, and accordingly, a directive based on each country's cultural and religious issues can be formulated. This study protocol includes informative information for designing and conducting of health professionals intending to create a direct on qualitative, theoretical, philosophical, spiritual, and moral health aspects.25

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Changes in ho`w ICU nurses perceive the DNR decision and their nursing activity after implementing it. Nurs Ethics. 2011;18:802-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perioperative do-not-resuscitate orders: It is time to talk. BMC Anesthesiol. 2013;13:1.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Futile” care: Do we provide it? Why? A semistructured, Canada-wide survey of intensive care unit doctors and nurses. J Crit Care. 2005;20:207-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Futile care; concept analysis based on a hybrid model. Glob J Health Sci. 2014;6:301-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Institutional ethics policies on medical end-of-life decisions: A literature review. Health Policy. 2007;83:131-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for end-of-life and palliative care in Indian intensive care units’ ISCCM consensus ethical position statement. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2012;16:166-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 2010. Guidelines for the Ethical Care of Patients with Do Not Resuscitate Orders. Available from: http://www.asahq.org/For-HealthcareProfessionals/Standards-Guidelines-andStatements.aspx

- [Google Scholar]

- End-of-life care in hospital: Current practice and potentials for improvement. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:711-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Life-sustaining medical treatment for terminal patients in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:1-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Compliance with DNR policy in a Tertiary Care Center in Saudi Arabia. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:2149-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health economics of a Palliative Care Unit for terminal cancer patients: A retrospective cohort study. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:29-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- European resuscitation council guidelines for resuscitation 2010 section 4. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2010;81:1305-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. 2004. Guideline Development Methods: Information for National Collaborating Centres and Guideline Developers. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; Available from: http://www.nice.org

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for guidelines: Are they up to the task? A comparative assessment of clinical practice guideline development handbooks. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49864.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guide to the development of clinical guidelines for nurse practioners. Western Australia: Office of the Chief Nursing Officer; 2007.

- Review of guidelines for good practice in decision-analytic modelling in health technology assessment. HTA Journal. 2004;8:201-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Consensuse Project. In: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; 2009.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethics and the law: Mental incapacity at the end of life. End Life Care. 2007;1:74-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Nominal Group Technique: A useful consensus methodology in physiotherapy research. NZ J Physiother. 2004;32:126-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Updating the guideline methodology of the healthcare infection control practices advisory committee (HICPAC). Atlanta: CDC; 2009.

- WHO Handbook for Guideline Development. 2010. WHO. Available from: http://www.who.int

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical practice guideline development manual: A quality-driven approach for translating evidence into action. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(6 Suppl 1):S1-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Signguideline. 2011. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). A Guideline Developer's. Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk

- [Google Scholar]

- Advisory Committee on Health Research Report to the Director General. In: Held at WHO Headquarters. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

- [Google Scholar]