Translate this page into:

Why Newly Diagnosed Cancer Patients Require Supportive Care? An Audit from a Regional Cancer Center in India

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Purpose:

The present study was planned to record the distressing symptoms of newly diagnosed cancer patients and evaluate how the symptoms were addressed by the treating oncologists.

Materials and Methods:

All newly diagnosed cancer patients referred to the Department of Radiotherapy during May 2014 were asked to complete a questionnaire after taking their consent. The Edmonton symptom assessment scale-regular questionnaire was used to assess the frequency and intensity of distressing symptoms. The case records of these patients were then reviewed to compare the frequency and intensity documented by the treating physician. The difference in the two sets of symptoms documented was statistically analyzed by nonparametric tests using SPSS software version 16.

Results:

Eighty-nine patients participated in this study, of which only 19 could fill the questionnaire on their own. Anxiety was the most common symptom (97.8%) followed by depression (89.9%), tiredness (89.9%), and pain (86.5%). The treating physicians recorded pain in 83.1% whereas the other symptoms were either not documented or grossly underreported. Anxiety was documented in 3/87 patients, but depression was not documented in any. Tiredness was documented in 12/80 patients, and loss of appetite in 54/77 patients mentioning them in the questionnaire. Significant statistical correlation could be seen between the presence of pain, anxiety, depression, tiredness, and loss of appetite in the patients.

Conclusion:

The study reveals that the distressing symptoms experienced by newly diagnosed cancer patients are grossly underreported and inadequately addressed by treating oncologists. Sensitizing the oncologists and incorporating palliative care principles early in the management of cancer patients could improve their holistic care.

Keywords

Developing countries

India

Newly diagnosed cancer

Supportive care

Unmet needs

INTRODUCTION

In the past few decades, most of the countries have experienced a health transition that resulted in a dramatic shift in the disease burden from communicable and nutrition-related diseases to noncommunicable diseases. Among the global deaths in 2008, 63% were attributed to noncommunicable diseases, and the toll is expected to increase further with aging of population, urbanization and globalization of risk factors.[1] One of the major differences between these communicable and noncommunicable diseases is the need for regular supportive care in the latter.

Among the noncommunicable diseases, malignancies constitute 21% of the total disease burden.[2] Owing to the progressive nature of the most cancers, palliative and supportive care assumes even more importance compared to other noncommunicable diseases. Ideally, palliative care should be initiated as early in the course of the disease as possible as a part of continuum of holistic care. Various studies have shown that early initiation of palliative care significantly improves survival, apart from quality of life of cancer patients.[3]

However, in resource-limited scenarios of developing world facing a dearth of palliative care specialists, supportive and palliative care are often restricted to pain management and end of life care and are instituted after all cancer-directed therapies have been exhausted. With increasing proportion of aged population and effective control of infectious diseases, incidence of cancers in developing countries is expected to raise at least three-fold in the next two decades.[456] This will further increase the burden on the healthcare system, making it even more difficult to deliver holistic care.

Optimal delivery of holistic care to cancer patients requires needs assessment with due consideration to social, cultural, and family situations as the first step, followed by appropriate policy-making to ensure that actions mirror the needs and expectations of cancer patients. Since 2012, palliative care has been recognized as a postgraduate specialty by the Medical Council of India, largely owing to the efforts of the Indian Association of Palliative Care.[7] This might be considered as a milestone in the history of palliative care in India, and enhanced the much-needed hope for development of holistic care. Apart from these ongoing efforts to increase the number of palliative care specialists, increasing awareness among the treating oncologists and sensitizing them to the palliative needs of cancer patients will be an effective strategy for improving holistic cancer care in developing countries.

This study was planned to understand the symptom burden in newly diagnosed cancer patients and evaluate how these symptoms were being addressed by the treating oncologists in a tertiary care center where specialist palliative care is limited to advanced or terminal cases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All newly diagnosed cancer patients referred to the Department of Radiotherapy during May 2014 were included in this study. After obtaining informed consents, all the patients were asked to fill the Edmonton symptom assessment scale-regular (ESAS-r) questionnaire[89] to assess the frequency and intensity of their symptoms (set A). If the patient was not able to fill the questionnaire due to illiteracy, cognitive impairment, or any other reason, assistance of caregivers was sought.

The treating oncologists were blinded to these details. Case records of these patients were later reviewed, and the frequency and intensity of all the symptoms documented by the oncologists were recorded (set B).

Descriptive statistics were obtained using SPSS version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For each symptom in ESAS-r questionnaire, proportion of cases documented by the treating oncologists (from set B) was compared with the actual proportion of cases obtained from patient-reported questionnaire (from set A), using the Chi-square test.

For further analysis, intensity of the patient-reported symptoms in set A was empirically stratified as mild (ESAS 1-3), moderate (ESAS 4-7), and severe (ESAS 8-10). For each symptom, the likelihood of being recorded by the oncologist in set B was correlated with the severity of the symptom reported by the patient in set A, using Spearman's rank correlation.

RESULTS

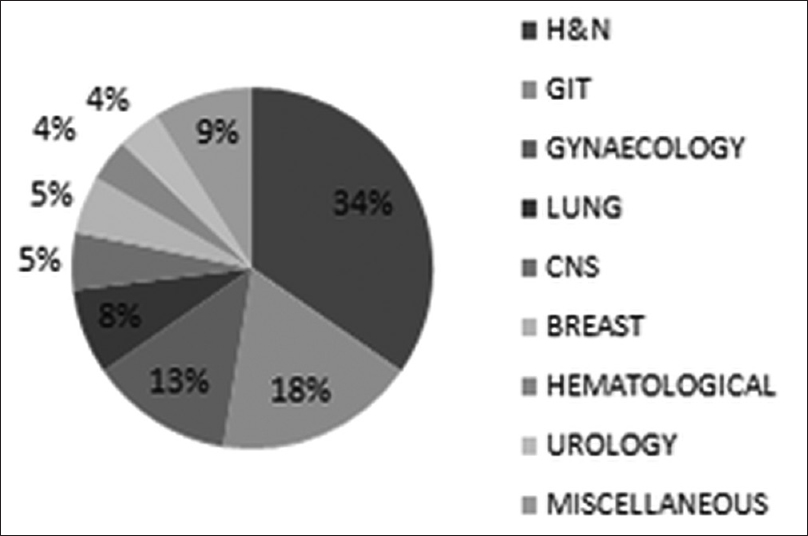

Eighty-nine patients participated in this study, of which only 19 (21.3%) could fill the questionnaire on their own whereas remaining needed assistance from caregivers. Among them, 48 were males and 41 were females. Median age of the studied population was 46 years (range 18-73 years). Site-wise distribution of the primary tumors is presented in Figure 1.

- Site-wise distribution of primary tumors in the studied population

Among the symptoms recorded by the patients, anxiety and loss of sense of well-being was the most common, present in 97.8% of the patients. Depression and tiredness were reported by 89.9% of the patients. Pain and loss of appetite were present in 86.5% of the patients. Drowsiness was reported by 74.2% of the patients while 57.3% experienced nausea. Shortness of breath was present in 50.6% of the patients.

About 60% of the patients who reported having pain, tiredness, and loss of appetite had moderate to severe symptoms. More than 85% of the patients reporting nausea and dyspnea had only mild symptoms. About 50% of the patients reporting anxiety and loss of sense of well-being had severe symptoms. Moderate to severe depression was present in 50% of the patients. About 70% of the patients who reported drowsiness had only mild symptoms.

Significant statistical correlation was seen between the presence of pain, anxiety, depression, tiredness, and loss of appetite in these patients. Patients with cancers of breast, gynecological sites, and prostate had higher levels of anxiety whereas those with head and neck, lung, and pancreatic cancers were more frequently depressed.

The treating oncologists recorded and addressed pain in 83.1% of the patients whereas other symptoms were either not documented or grossly underreported [Figure 2]. Anxiety was documented only in 3.4% of the patients, and tiredness in 13.5% of the patients. Depression and drowsiness were not documented in any patient. Loss of appetite was documented in 60.7% of the patients, and shortness of breath in 38.2% of the patients. This difference between the two sets of symptoms is statistically significant for all the symptoms (P < 0.05) except for pain (P = 0.57).

- Difference in prevalence of symptoms reported by patients and documented by physicians

There was a significant correlation between the severity of symptoms and the likelihood of their documentation, in case of pain, nausea and loss of appetite.

DISCUSSION

Supportive care can be defined as care that helps a person diagnosed with cancer and his family to cope with the disease, and extends from the pre-diagnosis phase, through the process of diagnosis and treatment, to cure, progression or death and into bereavement.[10] Apart from diagnosis and management of physical effects of cancer and its treatment, holistic care should address the psychological and psychosocial needs of cancer patients.

After the earliest reports on supportive care needs by the American Cancer Society in 1979, numerous studies have evaluated the unmet needs of cancer patients in various domains, over different time periods along the course of cancer progression.[1112] A systematic review by Harrison et al. identifies that supportive care needs of cancer patients are diverse during different phases in the cancer journey, and that this diversity was highest in the treatment phase.[12] The same review, however, highlights a paucity of evidence regarding the unmet needs of newly diagnosed cancer patients. With evolving evidence suggesting a detrimental effect of unmet needs on survival of cancer patients, early initiation of supportive care assumes even greater importance.[31314]

Contrasting with the Western World, supportive and palliative care in developing countries is still an evolving specialty. In India, about a million cancer patients are diagnosed each year and more than half of them are likely to die within a year of their diagnosis.[45] This number is expected to raise at least three-fold in the coming decade. However, the number of palliative care specialists necessary for catering the needs of these patients is not expected increase proportionately, due to limited resources.

Apart from this, poorly standardized taxonomy of supportive care needs and challenges with quantification resulted in a lack of consistent reporting methods that can be easily applied in developing countries where most patients are non-English speaking. In addition, low educational status and lack of general awareness with dependency on family members among a majority of patients in developing countries often complicate the scenario, as reflected in our study where barely one-fifth of our patients could fill the questionnaire on their own while the rest needed assistance from their caregivers.

Owing to these inadequacies, palliative care practice in India had long since been restricted to pain management and terminal care. In our institute, about 5,447 patients were diagnosed with cancer in the year 2013 whereas only 894 patients were registered in the palliative clinic in that year. Thus, the palliative care needs of five out of every six patients were being met with by the treating oncologist whereas only the patients with advanced disease or intractable symptoms were being addressed by palliative care specialists. At most peripheral centers in developing countries, availability of specialist palliative care services is even scarcer.

One of the most cost-effective policies for catering the unmet demands of newly diagnosed cancer patients would be incorporation of palliative care principles into regular oncology practice. However, lack of awareness among the already overburdened oncologists of the developing world, regarding the prevalence of distressing symptoms in newly diagnosed cancer patients, often results in inadequate documentation and addressing of most of these symptoms.

Being the most distressing symptom, pain is often documented and well addressed by the oncologists. Western literature projects that over three-fourths of all newly diagnosed cancer patients experience some degree of pain whereas the prevalence was 86% in our study.[15] There was no significant difference between the reported and documented prevalence of pain in our study.

Fatigue is a fairly common symptom that is often neglected in clinical practice. Studies have reported prevalence of fatigue in more than 91% of cancer patients.[16] Tiredness and fatigue were reported by 89.9% of the patients in our study whereas they were documented in only 13.5% of the patients although two-thirds of these patients had moderate to severe symptoms. Apart from inherent vagueness in taxonomy and quantification of fatigue and tiredness, scarcity of effective treatment options might attribute to lack of documentation by the treating oncologists in our study.

Literature reviews have documented that up to 69% of cancer patients might suffer from depression at some point of time during their course of illness.[17] In our study, depression was reported by 89.9% of the patients, half of whom had moderate to severe symptoms. This difference in prevalence might be attributed to various sociocultural factors, inadequate reporting, and probable use of more specific tools for evaluation of depression in western literature. Alarmingly, depression was not documented in any of the patients in our study, reflecting a gross lack of awareness among the treating oncologists.

Prevalence of anxiety in our study was even higher than that of depression. Among the 97.8% of the patients who reported anxiety at the time of diagnosis, more than 50% had severe symptoms. However, it was recorded and treated only in 3.4% of these patients, probably because anxiety associated with cancer diagnosis was transient and resolved with counseling in most patients.

Although nausea and shortness of breath were reported by half of the patients in our study, about 85% of them experienced only mild symptoms. Documentation was done only in a small proportion of cases, and there was a positive correlation between the likelihood of documentation and severity of symptoms.

Drowsiness was reported by 74.2% of the patients, but it was not documented in any, probably because more than 70% of these patients had only mild symptoms. About 86.5% of the patients had loss of appetite whereas it was addressed only in 60.7% patients. However, those patients who had moderate to severe loss of appetite were relatively well addressed.

Unmet needs in other domains related to access to information, activities of daily living, economic, and psychosocial needs etcetera were reported in up to 5-69% of the patients in various studies from the developed world; however, these were not analyzed in our study.[181920]

CONCLUSION

Palliative care, in developing countries, is still an evolving specialty. Due to limited resources, availability of specialist palliative care is often restricted to patients with advanced cancers or intractable symptoms. Apart from increasing the availability of specialist palliative care services, incorporating the principles of palliative care into regular oncology practice might be a cost-efficient strategy. However, due to lack of awareness among the treating oncologists, most of the supportive care is being restricted to pain management in many centers, resulting in underreporting of other distressing symptoms in newly diagnosed patients. Sensitizing the oncologists regarding the supportive care needs of cancer patients and incorporating palliative care principles early in the management of cancer patients could improve the holistic care in developing countries.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Providing palliative care for the newly diagnosed cancer patient: Concepts and resources. Oncology (Williston Park). 2008;22:29-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2015. Fact Sheet, Non Communicable Diseases. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs355/en

- Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improving cancer care in India: Prospects and challenges. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2004;5:226-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care for cancer patients in India: Are we doing enough. JAMA India. 2002;1:62-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2000. Medical Council of India Postgraduate Medical Education Regulations. :37. Available from: http://www.mciindia.org/rules.and.regulation/Postgraduate-Medical-Education-Regulations-2000.pdf

- The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): A simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7:6-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) as an audit tool. J Palliat Care. 1999;15:14-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer. In: Research Evidence Manual. London, England: National Institute of Clinical Excellence; 2004.

- [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. In: Report on the Social Economic and Psychological Needs of Cancer Patients in California. San Francisco, CA: Greenleigh Associates; 1979.

- [Google Scholar]

- What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1117-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Concerns. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press; 2008.

- The physical and psycho-social experiences of patients attending an outpatient medical oncology department: A cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 1999;8:73-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oxford handbook of palliative care. USA: Oxford University Press; 2005.

- Evidence report on the occurrence, assessment, and treatment of fatigue in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;32:40-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and management of depression in palliative care. In: Handbook of psychiatry in palliative medicine. USA: Oxford University Press; 2000. p. :25-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial needs of older cancer patients: A pilot study abstract. Medsurg Nurs. 1996;5:253-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The supportive care needs of newly diagnosed patients with cancer: A pilot study. Melbourne: The Cancer Council Victoria; 2004.

- The supportive care needs of newly diagnosed cancer patients attending a regional cancer center. Cancer. 1997;80:1518-24.

- [Google Scholar]