Translate this page into:

Palliative Care in Musculoskeletal Oncology

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Patients in advanced stages of illness trajectories with local and widespread musculoskeletal incurable malignancies, either treatment naive or having recurrence are referred to the palliative care clinic to relieve various disease-related symptoms and to improve the quality of life. Palliative care is a specialized medicine that offers treatment to the disease-specific symptoms, places emphasis on the psychosocial and spiritual aspects of life and help the patients and their family to cope with advance stage cancer in a stronger and reasonable way. The overall outcome of musculoskeletal malignancies has improved with the advent of multidisciplinary management. Even then these tumors do relapse and leads to organ failures and disease-specific deaths in children and young adults in productive age group thus requiring an integrated approach to improve the supportive/palliative care needs in end-stage disease. In this article, we would like to discuss the spectrum of presentation of advanced musculoskeletal malignancies, skeletal metastasis, and their management.

Keywords

Bone tumors

Musculoskeletal oncology

Palliative care

INTRODUCTION

“Best supportive care”/end of life care is the care that helps all those with advanced, progressive, incurable illness to live as well as possible until they die. It enables the supportive and palliative care needs of both patient and family to be identified and met throughout the last phase of life and into bereavement. It includes management of pain and other symptoms and provision of psychological, social, spiritual, and practical support.[1] Patients suffering from malignant musculoskeletal tumors with widespread metastatic disease, where curative treatment is not possible with any available modality of treatment needs palliative care. Bone and soft tissue sarcomas are known to have moderate to high risk of developing distant metastasis before the initiation or during the course treatment. Approximately, 20-25% of osteosarcoma presents with lung metastasis and about 40% are known to develop distant metastasis at later stages.[2] Even though overall survival for chondrosarcoma is reasonable (70% at 5 years), few subtypes such as mesenchymal and dedifferentiated subtypes have dismal prognosis.[3] Ewing sarcoma is a systemic disease, which is also associated with high rates of systemic failures either at presentation, during, or immediately after the treatment completion. Similarly, soft tissue sarcomas are also known to disseminate leading to end-stage disease in about 50-60% of all diagnosed cases.[4] Despite advances in local control, adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy, metastatic relapse after an initial clinical remission remains a significant clinical problem with 5-year survival for nonmetastasis bone and soft tissue sarcomas ranging from 50 to 75% with further significant drop for metastatic disease.[5] These aggressive bone and soft tissue sarcomas mainly affect adolescent and adults in their productive period of life and affect them physically, psychologically, and spiritually requiring a holistic approach to address their needs.[6]

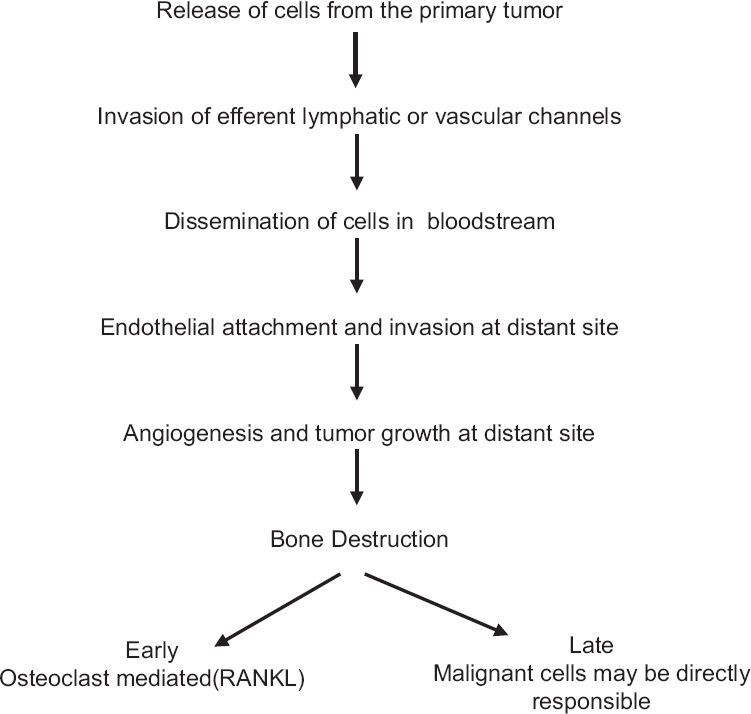

Apart from primary bone sarcomas, skeletal system is a common site for disease dissemination from visceral malignancies such as lung, prostate, breast, thyroid, and kidney. Although there is availability of diagnostic tools, systemic and local therapy, the burden of primary malignancies and prevalence of skeletal metastasis has increased many folds. More than 50% of lung cancer, breast cancer, and prostate cancer patients develop skeletal-related events (SRE) at diagnosis or during the treatment. SRE can present with pain, pathological fracture, or with spinal cord compression (with or without neurological deficits) causing major morbidities and compromises the quality of life [Figure 1].[7] It poses an incredible challenge for palliative medicine to deal with all these end-stage disease patients who present at varied age groups with diverse social, economical, and spiritual agony. The treatment has to be tailored to the individual patient need for better quality of life. The present article discusses the various presentations of terminally ill patients with musculoskeletal primary and secondary malignancies and related treatment and rehabilitation.

- Mechanism of metastasis and bone destruction

Pain management in primary and metastatic musculoskeletal tumors

Pain arising from the primary site of the tumor or the site of skeletal metastasis of musculoskeletal sarcoma or other carcinomas is one of the most important causes of distress and discomfort for palliative care patient [Table 1]. Effective pain management makes the patients comply with the treatment protocol. The treatment offered should be individualized according to the disease status, existing comorbidities, and the intensity and severity of symptoms. The treatment approach should be least invasive, safe, fast acting, effective, and sustainable.

Genesis of pain

Skeletal pain occurs due to loss of normal bony strength by destruction of bony architecture by tumor cells. This can occur at the site of the primary tumor or at metastasis in other bones. Skeletal system is a very common site for metastasis in primary musculoskeletal sarcomas as well as from other malignancies. 37–70% of all cancer patients develop skeletal metastasis at some stage of their life.[8] Apart from metastasis in appendicular leading to pathological fractures, axial skeleton metastasis is associated with pathological fractures and spinal cord compression leading to paraparesis or distal neural deficits.[9] Visual analog scale is the most common scale used for objective pain measurement[10] [Figure 2].

- Mechanism of musculoskeletal pain: Neoplastic cells secrete diverse cell factors to promote proliferation and stimulate osteoclastic bone resorption via receptor activator of nuclear factor‑kappa‑B ligand/ receptor activator of nuclear factor‑kappa‑B pathway in osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Osteoclasts create an acidic microenvironment by secreting H+ ions causing dissolution of bone minerals causing structural disintegration which may lead to pathological fracture. The acidic microenvironment excites sensory neurons in the bone by the activation of acid‑sensing nociceptors transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 and acid‑sensing ion channel 3, transducing noxious signals via the dorsal root ganglion (primary afferent neuron) and then the spinal cord (secondary afferent neuron) and causes the sensation of pain

Measures for pain control

Achieving an effective pain control in the end stage disease is an art, which requires a multipronged approach [Table 2].[11] This involves a detailed explanation and counseling of the patients and the attendants regarding the disease process and prognosis, alteration of the pathological process, addition of local therapy to halt or retard disease process, interruption of the pain producing pathways, lifestyle modification, and use of orthotics and prosthesis and sometime immobilization. Pain can be dealt with nonpharmacological and pharmacological approaches. Brad et al. in their study showed that music could reduce anxiety, pain, and improve mood and quality of life.[12] Jane et al. concluded that massage therapy could reduce the intensity of pain, improve quality of sleep and mood.[13] The pharmacological approaches available are medication, nerve blocks, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), radiotherapy, chemotherapy, embolization, cryoablation, high frequency focused ultrasound, vertebroplasty, and kyphoplasty.[14] The basic and initial approach that is used is ‘medication by the mouth, by the clock and the by the WHO ladder.[15]

Bone strengthening agents such as bisphosphonates and newer agents such as monoclonal antibody to receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa-B ligand (RANKL) (denosumab) are proven to reduce the SRE in both lytic and blastic bone metastasis.[1617] They prevent osteolysis, hypercalcemia, microfractures, and vertebral collapse thus reducing the bone pain and improving the patient quality of life. Zolendronic acid is the most potent and commonly used bisphosphonates with associated side effects such as anemia, gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation), fatigue, fever, weakness, arthralgia, myalgia, and less commonly, hypocalcaemia. Serious complication associated with amino-bisphosphonates is osteonecrosis of jaw, a dental evaluation, and preemptive dental treatment are mandatory before starting treatment. Bisphosphonates require dose adjustment in patients with renal insufficiency. Calcium and Vitamin D supplementation helps to prevent hypocalcemia.[16] Denosumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody to RANKL, is a more potent inhibitor of osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. It has been approved for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis as well as bone metastases from solid tumors and multiple myeloma. Denosumab was reported superior to zoledronic acid in preventing SRE. It is easier to administer, does not require dose adjustments for renal insufficiency and not associated acute reactions. The main drawback of this drug is its high cost.[17] The effects of these drugs are well-documented in metastatic carcinomas.

Radiotherapy is a noninvasive and one of the most effective modalities for the management of pain in palliative setting. For palliative pain relief, single fraction (8-10 Gy) and multifraction (30 Gy in 10 fraction) radiotherapy have shown similar efficacy, the rate of reradiation and pathological fracture are more associated with single-fraction treatment.[1819] Koontz et al. treated 21 cases of metastatic Ewing sarcoma with palliative radiotherapy (Median dose-30 Gy) and showed complete response to symptoms in 55% and partial response at 29% of sites.[20]

Numerous minimally invasive procedures are available if the radiation fails to achieve desired pain control. RFA, cryoablation, high frequency focused ultrasound, image-guided percutaneous cementing and microwaves are proven to be effective in reducing pain and increasing bone strength.[21] In RFA, an alternative current is applied at the target tissue with the help of interstitial electrodes, the current produces oscillating tissue ions which results in the frictional heat at target tissue. The disadvantages include increased tissue impedance resulting in limited application of additional current, skin burns, and thermal injury to surrounding vital structures.[22] Callstrom et al. reported good pain relief with cryoablation in skeletal lesions with advantage over RFA in terms of pain experienced during and post procedure and better visualization of ablation margin avoiding injury to surrounding tissue.[23] Image-guided percutaneous cement installation can prevent impending pathological fracture and the pain, mainly useful in spine and weight bearing bones. Thermal heat generated during polymerization of cement damages nerve endings and reduces pain and because of its mechanical property, it gives structural support to weak bone.[24] Combination of RFA and cementoplasty has shown a significant decrease in pain in lytic bone lesions with decrease in mean visual analog scale score of 8.5-3.5[25] [Figure 3]. High-frequency focused ultrasound is done under magnetic resonance imaging where rapid heat is generated within the tissue (temperature of 65-85°C) and destroy the tissue by coagulation necrosis. HIFFU is contraindicated in the lesions, which are close to neurovascular bundle, spinal cord, and small superficial lesions close to skin. Recent studies have demonstrated significant pain relief as well as control of primary lesions with HIFU.[26]

- (a) Computed tomography image showing carcinoma of the lung. (b) Computed tomography image showing skeletal metastasis in the proximal femur with intact cortex all around. (c) Image showing percutaneous cement injection after radiofrequency ablation. (d) Radiograph showing cementoplasty of the proximal femur defect

Pathological fracture

Patients can present impending or complete pathological fractures which add significant morbidity. Depending on the survival and prognosis, the treatment modality can be either conservative or aggressive. The intent of the procedure would always be palliative. The main goal of the procedure is early mobilization so that patient is capable of independent self-care. This is achieved by structurally replacing the damaged host bone by metallic endoprosthesis or by fixing the fracture with adequate implants and bone cement [Figure 4]. The main aim is to have a reconstruction, which should outlive the patient's expected lifespan.[27] Plaster immobilization or functional brace is the age-old basic method of fracture stabilization; it can be a temporary makeshift and in some cases can be continued as the definitive management if life expectancy is extremely poor. Impending pathological fractures should be graded as per Mirels’ scoring system ([Table 3] Mirels’ scoring system for impending pathologic fractures),[28] which guides a surgeon to take a decision for prophylactic fixation or to treat it with conservative methods.[27] Immediate stabilization and early mobilization can be accomplished with preferably intramedullary stabilization (weight sharing devices) and filling of the defect with bone cement. This kind of construct would give immediate stability instead of depending on the hosts’ body response and bone to heal and that too in a setting where the healthy bone has been replaced by metastatic deposits. Peritrochanteric fractures in lower limbs and lesions with large bone defect are preferably treated with replacement arthroplasty. Patients with minimal vertebral collapse (>50% of vertebral height) with no neurological deficit are treated with bracing and radiotherapy. Unstable spine, multiple vertebral compression, or patients with neurological deficits are managed by spinal decompression with instrumentation [Figure 5]. Bone cement can be used in vertebroplasty and acetabuloplasty in contained vertebral collapse and periacetabular metastasis, respectively. This will palliate both pain, prevent the ongoing postural deformity, and will enhance the mobilization of these patients.[2930] Amputation as a palliative procedure has been well-documented for advanced bone and soft tissue tumors. Pain alone should not be a deciding factor for major amputations unless it involves complications such as fracture, hemorrhage, and/or fungation. According to Malawer et al.,[31] the indications for palliative major amputations include involvement of a proximal limb or a major joint, accompanied by intractable pain, sepsis, tumor fungation, hemorrhage, vascular thrombosis, pathologic fractures, radiation-induced necrosis, or a limb with severe functional impairment [Figure 6].

- (a) Bone scan showing extensive skeletal metastasis of a breast carcinoma patient. (b) Radiograph showing pathological fracture of the proximal femur. (c) Radiograph showing replacement of diseased and fractured proximal femur with megaprosthesis for better quality of life

- (a) Computed tomography image showing hepatocellular carcinoma. (b) Radiography showing collapse of the C5 secondary to metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma. (c) Sagittal T1 magnetic resonance image showing collapse of the C5 vertebra and compression of spinal cord. (d and e) Radiographs showing anterior decompression of the spinal cord and stabilization of C5 with plate

- (a) Radiograph showing osteosarcoma of proximal femur with pathological fracture with plate in situ (b) T1 axial magnetic resonance image showing osteosarcoma of proximal femur with soft tissue component. (c) Clinical picture showing large swelling in the proximal femur with surgical scar. (d) Patient underwent palliative hindquarter amputation in view of extensive metastasis. Radiograph showing post hindquarter amputation status

Tumor fungation

Tumor fungation generally occurs at the site of primary tumors. In aggressive bone and soft issue tumors, discrepancy between the rate of growth and the vascular supply of the feeding vessel frequently give rise to foul smelling fungating tumor mass.[32] Necrosis of the overlying epithelium makes the surface raw, resulting in bleeding, accumulation of the blood clot and resulting in secondary anaerobic infection. This poses a serious concern for the patient as well as the caregivers and the attendants. Management: Regular dressing of the wound and keeping the surrounding area clean with application of antibiotic creams; locally acting hemostatic agents will help. Patients with huge unresectable tumors with frequent intratumoral bleeding can be managed with hemostatic radiotherapy (mean dose 20 Gy).[33] Bleeding tumors in the inaccessible area such as pelvis and spine can be treated with angioembolization. Palliative limb ablative surgery may be required for large fungating and bleeding tumors in extremities.

Lymphedema

Patients presenting with lymphedema and brawny edema with glossy skin is one of the most common presentations in palliative clinic. It may be due to compression of lymphatic drainage by primary tumors, secondary to previous surgeries, postradiation or due to metastatic involvement of the draining lymph node.[15] Severe lymphedema can result in functionless limb. The main concerns are to decrease or to control the lymphedema, prevent secondary infection, prevention of pressure sores, care of dry and glossy skin and fissures. Management: Basic measures taken to prevent lymphedema are limb elevation, elastic stockings, custom made sleeves, gentle message, and judicious use of diuretics.[15] Patients with functionless limb due to severe lymphedema, not responding to standard treatment can be offered palliative amputation.

Gastrointestinal symptoms

Patients presenting with nausea and vomiting is not very uncommon in palliative bone and soft tissue sarcoma patients. Most commonly, it is drug induced. However, care must be taken to identify the specific receptors responsible for the symptoms as because the management is entirely receptor targeted.[34] Drugs such as morphine used as potent analgesics act on the chemoreceptor trigger zone and may produce nausea and vomiting. All these may be a deterrent in taking effective treatment. Dopamine antagonist such as haloperidol and metoclopramide provide good relief. Vomiting can be also due to stimulation of 5 HT3 receptors, most often by stretch of the gut wall, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy or due to stasis caused by obstruction.[35] Cancer patients generally are cachectic have loss of appetite due to both the disease process and cytotoxic therapy. Consequently, their intake is decreased resulting in chronic constipation. Patients taking opioid analgesics suffer from constipation as a side effect from the drug. Stool softener along with intestinal motility agents are recommended for opioid-induced constipation. Occasionally, a phosphate enema may be required for evacuating any retained fecal matter.

Respiratory distress

Lung being one of the most common sites of metastasis for musculoskeletal malignancies, patients presenting in the palliative clinic with respiratory distress are quite common. Distress can be due to large pulmonary metastatic deposits leading to insufficient pulmonary parenchyma or due to the presence of large pleural effusion or pneumothorax. Plain radiography of chest, ultrasonography, and computer tomography are the most commonly used imaging modalities to diagnose and plan the treatment in these cases. Chest physiotherapy with incentive spirometer, propped up position, intermittent moist oxygen inhalation, and nebulization with salbutamol will help to improve the patient condition. Image-guided or conventional therapeutic drainage of the fluid may relieve the patients of the distress. Malignant pleural effusions have a characteristic tendency of quick refill. This situation can be managed by pleurodesis by instillation of talc in the pleural cavity or antibiotics.[15] In refractory dyspnea, low-dose opioids such as morphine and benzodiazepines relieve the distress of breathing.

Psychological care

“Breaking the Bad News” is a challenge both for the doctors and the patients and their family. This is a situation, which everybody wants to avoid. It should be prompt, based on factual information and case notes and most essentially with the empathetic bent of mind. Anxiety comes from the symptoms of the end-stage disease and for the other family members regarding their future in his or her absence.[35] This anxiety-depression goes on in a vicious cycle and demoralizes the patient and affects the quality of life badly. Psychiatrist and the psychologist play a very vital role to make them understand the disease status and its outcome and to train them mentally and emotionally to face the situation. Regular counseling sessions can help the patients to manage their psychological distress. Screening for depression is important and small patient population will benefit from pharmacological management.

Systemic treatments

Hormonal therapies, newer receptor-specific drugs, and monoclonal antibodies have changed the treatment of metastatic carcinomas. Studies have shown significant improvement in survival and quality of life with these drugs.[3637] Low-dose metronomic chemotherapy has evolved as a newer bullet in the treatment of advanced refractory tumors. The basic concept of metronomic chemotherapy is to use low-dose multi drugs (due to heterogenecity of tumors) over a relatively long duration of time with no extended drug-free break. It mainly targets the angiogenesis of tumors resulting hypoxia and depletion of nutrition. These have resulted in significant improvement in the quality of life and survival in advanced tumors.[38] Thus, medical oncology plays a vital role in the management of palliative cancer patients.

CONCLUSION

Palliative care, in a nutshell, is the constellation of services that improves patient-related outcomes in advanced stages of cancer. The specialized care helps the patients and their families to cope with the perils of advanced illness. When a patient is declared “Best supportive care,” he or she is referred to the palliative care clinic where a holistic approach is commissioned to counsel the patients and their families, educate them and provide required evidence-based treatment to resolve the physical, psychological, and spiritual misery. Role of palliative care in bone and soft tissue sarcoma is immense because the inherently aggressive malignant tumors too often show local and distant recurrence in spite of multimodality treatment even in the best of the sarcoma treatment centers. This is the reason that from times long ago, hospice centers are operative throughout the country. Hospice centers are not just a place; it is an idea that enables patients to live well and die well. Palliative care requires the involvement of multidisciplinary approaches such as palliative medicine, Intervention radiology, radiotherapy, surgical oncology, and chemotherapy.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- National Council for Palliative Care 2006. 2008. The End of Life Care Strategy. Available from: http://www.ncpc.org.uk/sites/default/files/AandE.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- The identification of prognostic factors and survival statistics of conventional central chondrosarcoma. Sarcoma. 2015;2015:623746.

- [Google Scholar]

- Symptom burden, survival and palliative care in advanced soft tissue sarcoma. Sarcoma. 2011;2011:325189.

- [Google Scholar]

- Twenty Years on: What Do We Really Know about Ewing Sarcoma and What Is the Path Forward? Crit Rev Oncog. 2015;20:155-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Natural history of skeletal-related events in patients with breast, lung, or prostate cancer and metastases to bone: A 15-year study in two large US health systems. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:3279-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Radiofrequency ablation of osseous metastases for the palliation of pain. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:189-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical investigations on the spinal osteoblastic metastasis treated by combination of percutaneous vertebroplasty and (125) I seeds implantation versus radiotherapy. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2013;28:58-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methodological problems in the measurement of pain: A comparison between the verbal rating scale and the visual analogue scale. Pain. 1975;1:379-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pain syndromes in patients with cancer and HIV/AIDS. In: Portenoy RK, ed. Contemporary Diagnosis and Management of Pain in Oncologic and AIDS Patients. Newtown, PA: Handbooks in Healthcare; 1998. p. :44-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;8:CD006911.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of massage on pain, mood status, relaxation, and sleep in Taiwanese patients with metastatic bone pain: A randomized clinical trial. Pain. 2011;152:2432-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care and pain management in cancer. In: Puri A, Agarwal MG, eds. Current Concepts in Bone and Soft Tissue Sarcoma (1st ed). Mumbai: Paras Medical Books Pvt. Ltd.; 2007. p. :278-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term efficacy and safety of zoledronic acid in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma and other solid tumors: A randomized, Phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Cancer. 2004;100:2613-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Denosumab compared with zoledronic acid for the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced breast cancer: A randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5132-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases: An ASTRO evidence-based guideline. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:965-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative Supportive Care Group. Meta-analysis of dose-fractionation radiotherapy trials for the palliation of painful bone metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:594-605.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative radiation therapy for metastatic Ewing sarcoma. Cancer. 2006;106:1790-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Minimally invasive (percutaneous) treatment of metastatic spinal and extraspinal disease – A review. Acta Clin Croat. 2014;53:44-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous tumor ablation tools: Microwave, radiofrequency, or cryoablation – What should you use and why? Radiographics. 2014;34:1344-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous image-guided cryoablation of painful metastases involving bone: Multicenter trial. Cancer. 2013;119:1033-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combination radiofrequency ablation and percutaneous osteoplasty for palliative treatment of painful extraspinal bone metastasis: A single-center experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:1094-100.

- [Google Scholar]

- Radiofrequency ablation in combination with osteoplasty in the treatment of painful metastatic bone disease. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:419-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- High-intensity focused ultrasound in the treatment of bone tumors: Another treatment option for palliation and primary treatment? Cancer. 2010;116:3754-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- In brief: Classifications in brief: Mirels’ classification: Metastatic disease in long bones and impending pathologic fracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2825-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metastatic disease in long bones. A proposed scoring system for diagnosing impending pathologic fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;249:256-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current trends in mini-invasive management of spine metastases. Interv Neuroradiol. 2015;21:263-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Contemporary treatment with radiosurgery for spine metastasis and spinal cord compression in 2015. Radiat Oncol J. 2015;33:1-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Major amputations done with palliative intent in the treatment of local bony complications associated with advanced cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1991;47:121-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surgical management of very large musculoskeletal sarcomas. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1138:77-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinically significant bleeding in incurable cancer patients: Effectiveness of hemostatic radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7:132.

- [Google Scholar]

- Update on the management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting – Focus on palonosetron. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2015;11:713-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric aspects of chronic palliative care: Waiting for death. Palliat Support Care. 2012;10:205-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neoadjuvant and adjuvant hormonal and chemotherapy for prostate cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27:1189-204.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of metastatic breast cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12(5 Suppl):759-61.

- [Google Scholar]