Translate this page into:

Significance of End-of-life Dreams and Visions Experienced by the Terminally Ill in Rural and Urban India

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

End-of-life dreams and visions (ELDVs) are not uncommon and are experienced by many near the time of death. These visions can occur months, weeks, days or hours before death. We wanted to document ELDVs, if any, in rural and urban settings in India, where talking about death is usually considered a taboo and also to compare its incidence with the urban population.

Principle Research Question:

Do terminally ill patients receiving home care in rural and urban India experience ELDVs? If yes, then an enquiry into the nature of such ELDVs.

Study Design:

Prospective, cohort based, with a mixed-methods research design.

Methodology:

60 terminally ill patients with Palliative Performance Scale of <40, who consented to participate in the study were enrolled and questioned about the occurrence of ELDVs if any. Questions were both closed-ended and open ended regarding the content, frequency, recall, associated symptom burden, etc.

Results:

63.3% cases reported experiencing ELDVs. 55.5% of the rural patients reported ELDVs while 66.6% of the urban patients did the same. 78.9% (30) of the subjects were able to recall the ELDVs vividly and in detail, 13.1% (5) subjects were able to recall somewhat and 7.8% (3) subjects had trouble in recalling them. 84.2% (32) subjects reported the ELDVs as 'distressing'. 30 subjects (78.9%) reported seeing 'deceased' people, be it relatives, friends or acquaintances. 12 (31.5%) saw living friends and relatives, 52.6% (20) saw people or forms that they did not recognize, 21% (8) visualized making preparations or going on a journey. 76.3% (29) patients had a symptom burden of >7 (on a VAS of 1-10), which corresponded to 'severe distress'. 94.7% (36) patients felt much better having discussed their ELDVs with the team.

Conclusions:

The results of our study suggest that ELDVs are not uncommon in India and the incidence does not differ significantly between rural and urban population. Our subjects found them to be distressing initially, but felt better after discussing it with our team. There was a direct correlation between severity of symptoms and occurrence and frequency of ELDVs. Another finding exclusive to our study was that the persons visualized in ELDVs did not threaten or scare the patient and the known persons visualized were seen as they were in their prime of health. We feel that addressing such 'issues' is of paramount importance with a view to providing holistic care. I feel that they strongly suggest the presence of life after death and when properly explained, can reinforce a sense of hope.

Keywords

Dreams and visions

End of life

Terminally ill

INTRODUCTION

End-of-life dreams and visions (ELDVs) are not uncommon and are experienced by many near the time of death. It is estimated that 50–60% of conscious dying patients experience ELDVs.[1] The most prevalent ELDVs reported are those in which the dying patients describe seeing deceased family, friends, or religious figures. These visions can occur months, weeks, days, or hours before death.[1]

We wanted to document ELDVs, if any, in rural and urban settings in India, where talking about death is usually considered a taboo and also to compare its incidence with the urban population. Till date, there are no studies documenting ELDVs in India, while comparing them from the rural and urban perspective. The study was conducted in home-care settings and repeated visits were first undertaken to gain the confidence of the patient and the family, before encroaching on to the topic of ELDVs. The study was conducted in a culturally appropriate manner.

Aims and objectives

-

To enquire into the nature of dreams experienced by the terminally ill in rural India

-

To determine any pattern of consistency in such dreams (when compared to other terminally ill)

-

To determine the association of mortality, if any, with such dreams

-

To determine what effect the discussion of ELDVs had on the patients and their families.

Study design

Prospective, cohort-based, with a mixed-methods research design.

METHODOLOGY

-

Principle research question: Do terminally ill patients receiving home care in rural and urban India experience ELDVs? If yes, then an enquiry into the nature of such ELDVs

-

Type of study:

-

Part A: Having a quantitative research design

-

Part B: Qualitative with an explorative research design based on semi-structured interviews.

-

-

Participant group: Terminally ill patients receiving home-based care in rural and urban settings of India

-

Sample size: Using a confidence level of 95% and a confidence interval of 12.7 (calculated at 5% Type I error), we calculated our sample size to be 60. Interviews continued until there was saturation of themes from content analysis of the transcribed interviews

-

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

-

The inclusion criteria were:

-

Age 18 years or older

-

Capacity to provide informed consent

-

Palliative performance scale score of <40.[2]

-

-

The exclusion criteria were:

-

Refusal by the patient or objection by part of the family

-

Evidence of psychiatric disturbances or any such organic causes that might interfere with normal cognition such as electrolyte imbalance, delirium caused by pain, fever, and medications.

-

-

-

Methods

-

After winning the confidence of the patient and his family (often requiring repetitive visits), he/she was asked by the primary interviewer if he/she experienced ELDVs. The questionnaire was divided into two parts:

-

Part A: Comprising closed-ended questions viz.,

-

Do you experience ELDVs

-

When do you see them: Asleep, awake, or both

-

Do they occur at a particular time of the day

-

How frequently do you see them: Daily, weekly, and monthly

-

Do the dreams/visions seem real: Yes, no

-

Are you able to recall them: Yes, vividly; yes, somewhat; no

-

Are these experiences comforting or distressing

-

Who or what do you see in the dreams/visions: Deceased friends or relatives, living friends or relatives, other people, deceased pets or animals, living pets or animals, religious figures, and other

-

Did you discuss about your dreams/visions with anybody: Yes, no

-

Do you believe in God/are you religious? Yes, no

-

How severe is your symptom burden now on a scale of 1–10, 1 being no burden and 10 being extremely distressing burden load

-

Has the discussion of your ELDV with us/and family members (if permitted) helped you in feeling better: Yes, no (This was conducted at least 2 days after the interview on ELDVs).

-

-

Part B: This comprised open-ended questions to enquire into the content of the dreams/visions and its significance, if any, as perceived by the subject

-

-

The interview was carried out in an unhurried manner with minimal disturbance as far as practicable

-

The interview was carried out in the language in which the patient was comfortable with (Bengali, Hindi, and English)

-

The participants had the option of withdrawing from the study at any such point of time before the analysis of data began

-

All interviews were audio recorded and then translated into English, transcribed verbatim by the researcher which facilitated “immersion” into the data from the outset.

-

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

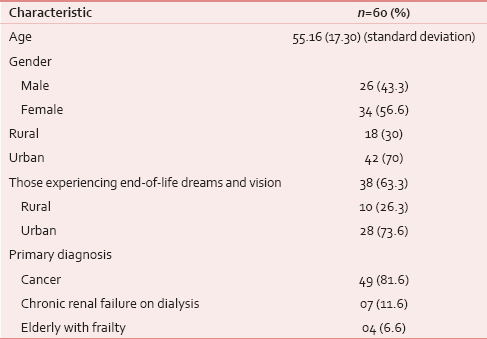

A total of sixty patients were interviewed at home after being enrolled for the study [Table 1]. The mean age was 55.16 years with a standard deviation of 17.30. There were more females (56.6%) than males. 30% were from rural settings. Cancer was the primary diagnosis in 81.6% cases.

Frequency and prevalence of dreams

About 63.3% cases reported experiencing ELDVs. 55.5% of the rural patients reported ELDVs whereas 66.6% of the urban patients did the same. However, none of the subjects spontaneously reported ELDVs; it was only on focused questioning that they reported it. When probed, most subjects did not report out of embarrassment and fear of ridicule. About 35 (92.1%) subjects had not discussed their ELDVs with anybody.

Eight subjects (21%) reported seeing ELDVs when they were asleep, 5 (13.1%) while awake, while the majority, 25 subjects (65.7%), reported seeing them in both states.

Twenty subjects (52.6%) reported that they saw ELDVs at a particular time, usually night.

Sixteen subjects (42.1%) reported having ELDVs daily, 14 on a weekly basis (36.8%), and 8 on a monthly basis or less frequently (21%).

Twenty-six subjects (68.4%) reported that the dreams seemed real.

About 30 (78.9%) of the subjects were able to recall the ELDVs vividly and in detail, 5 (13.1%) subjects were able to recall somewhat, and 3 (7.8%) subjects had trouble in recalling them.

About 32 (84.2%) subjects reported the ELDVs as “distressing.”

Content of dreams

Thirty subjects (78.9%) reported seeing “deceased” people, be it relatives, friends, or acquaintances. 12 (31.5%) saw living friends and relatives, 20 (52.6%) saw people or forms that they did not recognize, 8 (21%) visualized making preparations or going on a journey, and 1 (2.6%) reported seeing a “dead snake.” There was a considerable degree of overlap between the groups.

Patient characteristics

About 31 (81.5%) of the subjects were religious and believed in God. At the time of interview, 29 (76.3%) patients had a symptom burden of >7 (on a visual analog scale [VAS] of 1–10), which corresponded to “severe distress.” About 36 (94.7%) patients felt much better having discussed their ELDVs with the team. This was assessed 2 days after the initial visit. Furthermore, at this point of time, 36 (94.7%) subjects had a symptom burden of <4 as assessed by VAS.

Results of part B of the study

After repeated and comparative reading of the transcripts, we were able to extract the following themes from the transcripts:

-

The dream content mostly had explicit recall with clarity

“Everything was very clear… as if it was happening for real” (Interview 5).

-

ELDVs could occur at any time of the day

“They come mostly at night, but then there is no fixed time… I have seen him in day time as well” (Interview 17).

-

ELDVs are mostly disturbing

“I was scared and confused… she had died 6 months back… how could she be sitting next to me and smiling at me?” (Interview 3).

-

The persons visualized in ELDVs do not threaten or scare the patient

They never harm or frighten me. They are always smiling…” (Interview 45).

-

The known persons visualized are seen as they were in their prime of health

“My mother died of cancer. But, when I see her at night, she looks fresh, healthy, and wearing nice clothes” (Interview 19)

-

ELDVs seem very “real”

“I feel confused… I can't understand if it is a dream… it is so real… I see them, they sit next to me, walk about, talk to me…” (Interview 32).

-

Most patients have ELDVs when they become very sick and essentially bed-bound

“I have been seeing him (my deceased husband) since I have been bed-bound” (Interview 8).

-

With improvement of symptom burden, ELDVs decrease in frequency or disappear

“I feel much better now after the medications (for pain, constipation, nausea). The dreams do not come anymore… (Interview 1).

-

Most patients were clueless about the significance of their dreams

“I don't understand why I see them… I have never seen them before, so why now?” (Interview 30).

DISCUSSION

Palliative care is in its infancy in most parts of India with the result that most patients die painful and undignified deaths with unaddressed symptoms. Barriers include lack of accessibility and availability of care, lack of medications and their affordability and cultural acceptance. Provision of “home care” remains an economically and practically viable option of addressing these symptoms. Assessment of psychosocial and spiritual concerns is also of paramount importance in such resource-poor settings.

This study was undertaken with a view to assess the incidence and nature of ELDVs in India, with its rich cultural, spiritual, and religious heritage, and to compare the nature of ELDVs experienced between the rural and urban population.

About 63.3% of our subjects reported ELDVs, which is consistent with the findings of Mazzarino-Willet and Kellehear et al.[3] The dreams were vivid and had an explicit recall and clarity in most cases. This finding is consistent with the findings reported by Kerr et al.[4]

Thirty subjects (78.9%) reported seeing “deceased” people, be it relatives, friends, or acquaintances. Twelve (31.5%) saw living friends and relatives, 20 (52.6%) saw people or forms that they did not recognize, and 8 (21%) visualized making preparations or going on a journey. There was a considerable degree of overlap between the groups. However, like most previous studies, in our study too, there was a noted absence of religious content in the dreams/visions although 31 (81.5%) of the subjects were religious and believed in God.[456]

Interestingly, in our study, we found that ELDVs had a positive correlation with the symptom burden and decreased in frequency or disappeared as the symptom burden diminished. At the time of interview, 29 (76.3%) patients had a symptom burden of >7 (on a VAS of 1–10), which corresponded to “severe distress.” About 36 (94.7%) patients felt much better having discussed their ELDVs with the team. This was assessed 2 days after the initial visit. Furthermore, at this point of time, 36 (94.7%) subjects had a symptom burden of <4 as assessed by VAS.

Unlike most other studies,[47] 32 (84.2%) of our subjects reported the ELDVs as “distressing.” Most patients were clueless about the significance of their dreams. None of the subjects spontaneously reported ELDVs, it was only on focused questioning that they reported it. When probed, most subjects did not report out of embarrassment and fear of ridicule. About 35 (92.1%) subjects had not discussed their ELDVs with anybody.

Another finding exclusive to our study was that the persons visualized in ELDVs did not threaten or scare the patient and the known persons visualized were seen as they were in their prime of health.

Dr. Osis and Dr. Haraldsson have evaluated data from a 4-year study involving 50,000 deathbed observations by 1000 doctors and nurses. The study was cross-cultural with comparisons between the United States and India. Dr. Osis and Dr. Haraldsson made a careful characterization of the apparition experience in these terminal patients and separated hallucinations from experiences of reality. They conclude, “this evidence strongly suggests life after death – more strongly than any alternative hypothesis can explain the data.”[6] We strongly agree with the conclusions of Dr. Osis and Dr. Haraldsson.

Limitations of this study

Our study was more of a “cross-sectional” study, where the findings were documented at one point of time, though a repeat evaluation was done after 2 days of the initial visit. A longitudinal study would have been more appropriate where multiple interviews of the same patient over a period of time could be conducted and documented. This was not possible due to lack of funding for the study.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of our study suggest that ELDVs are not uncommon in India, and the incidence does not differ significantly between rural and urban population. Our subjects found them to be distressing initially, but felt better after discussing it with our team. There was a direct correlation between severity of symptoms and occurrence and frequency of ELDVs.

Another finding exclusive to our study was that the persons visualized in ELDVs did not threaten or scare the patient and the known persons visualized were seen as they were in their prime of health.

We feel that addressing such “issues” is of paramount importance with a view to providing holistic care. Palliative care professionals need to be sensitized to recognize and address such issues.

We strongly feel that there are many aspects which cannot be explained by science, and ELDVs are one of them. They strongly suggest the presence of life after death and when properly explained, can reinforce a sense of hope.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The author wishes to acknowledge the untiring efforts put in by Runa Mitra, Tulika, Debtirtha, Usha Mohanti and Dr. Nivedita Datta.

REFERENCES

- Deathbed phenomena: Its role in peaceful death and terminal restlessness. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27:127-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Deathbed visions from the Republic of Moldova: A content analysis of family observations. Omega (Westport). 2011;64:303-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- End-of-life dreams and visions: A longitudinal study of hospice patients' experiences. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:296-303.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comfort for the dying: Five year retrospective and one year prospective studies of end of life experiences. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;51:173-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- What they Saw at the Hour of Death: A New Look at Evidence for Life after Death. Norwalk, CT: Hastings House; 1997.

- Dreaming Beyond Death: A Guide to Pre-Death Dreams and Visions. Boston: Beacon Press; 2006.