Translate this page into:

The Relationship Between Ethnicity and the Pain Experience of Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Cancer pain is a complex multidimensional construct. Physicians use a patient-centered approach for its effective management, placing a great emphasis on patient self-reported ratings of pain. In the literature, studies have shown that a patient's ethnicity may influence the experience of pain as there are variations in pain outcomes among different ethnic groups. At present, little is known regarding the effect of ethnicity on the pain experience of cancer patients; currently, there are no systematic reviews examining this relationship.

Materials and Methods:

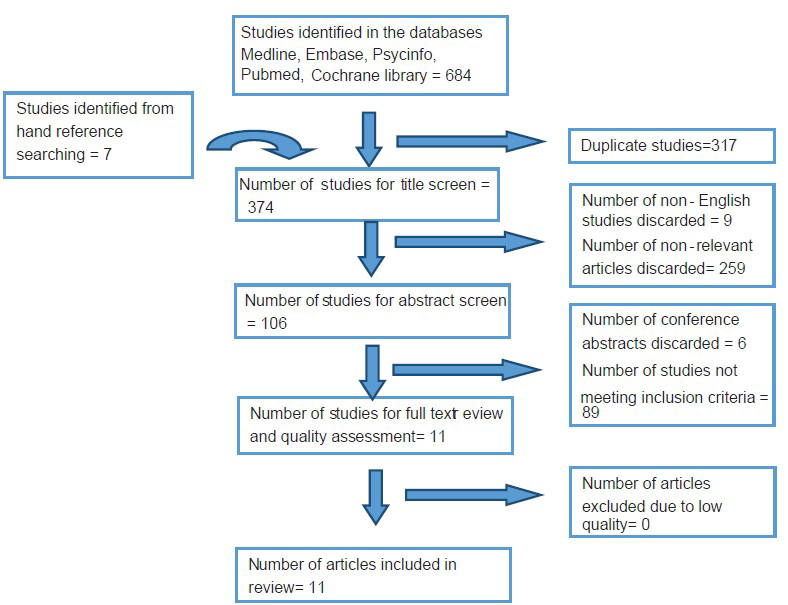

A systematic search of the literature in October 2013 using the keywords in Group 1 together with Group 2 and Group 3 was conducted in five online databases (1) Medline (1946–2013), (2) Embase (1980–2012), (3) The Cochrane Library, (4) Pubmed, and (5) Psycinfo (1806–2013). The search returned 684 studies. Following screening by inclusion and exclusion criteria, the full text was retrieved for quality assessment. In total, 11 studies were identified for this review. The keywords used for the search were as follows: Group 1-Cancer; Group 2- Pain, Pain measurement, Analgesic, Analgesia; Group 3- Ethnicity, Ethnic Groups, Minority Groups, Migrant, Culture, Cultural background, Ethnic Background.

Results:

Two main themes were identified from the included quantitative and qualitative studies, and ethnic differences were found in: (1) The management of cancer pain and (2) The pain experience. Six studies showed that ethnic groups face barriers to pain treatment and one study did not. Three studies showed ethnic differences in symptom severity and one study showed no difference. Interestingly, two qualitative studies highlighted cultural differences in the perception of cancer pain as Asian patients tended to normalize pain compared to Western patients who engage in active health-seeking behavior.

Conclusion:

There is an evidence to suggest that the cancer pain experience is different between ethnicities. Minority patients face potential barriers for effective pain management due to problems with communication and poor pain assessment. Cultural perceptions of cancer may influence individual conceptualization of pain and affect health-seeking behavior.

Keywords

Cancer

Culture

Ethnicity

Pain

INTRODUCTION

Cancer encompasses a range of diseases, each with varied presentations and clinical outcomes. The variety of symptoms in cancer-related conditions contribute to a significant burden for patients and caregivers, affecting their quality of life (QoL), physical functioning, and emotional well-being.[1] Chiefly, cancer pain is a common and highly distressing symptom, with its management forming an essential component of a comprehensive palliative care program. Pain management in a humane, cost-effective package represents a key challenge for health care staff globally.[2]

The pain experience

Dame Cicely Saunders was the first to define the concept of pain as a complex multifactorial construct.[3] The subjective and individualistic experience of pain results from interactions between multiple dimensions, such as physiological, affective, sociocultural, behavioral, cognitive, and sensory strands. A study by Ko et al., (2013)[4] showed a significant positive correlation between physical pain and depression as well as cognitive impairment, highlighting this intricate web of effect. A patient's sociocultural background can determine the psychological and cognitive reaction to a diagnosis of cancer, culminating in the pain experience. It is likely that the inability to recognize and assess the multidimensional nature of pain contributes to its undertreatment.[5]

Physicians use a patient-centered approach to treat cancer pain, placing a great emphasis on patient self-reported ratings of pain to guide therapeutic management options. In the literature, studies have indicated that a patient's ethnicity may influence the perception of pain as there are variations in pain outcome measurements among different ethnic groups.[678] Cancer is a disease of high symptomatic burden, and complex interactions with co-variables lead to a heterogeneous clinical presentation. At present, little is known regarding the effect of ethnicity on the pain experience of cancer patients or the possibility of different health care needs. Recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder framework[9] calls for an individualistic approach to cancer pain management, highlighting the need for an increased understanding of the role of a patient's psychosocial background in determining the pain experience.

Race, ethnicity, and culture

Race, ethnicity, and culture are terms commonly used with similar characteristics and subtle differences. The term “Race” refers to a classification based on an individual's physical appearance with skin color as the most prominent determinant.[10] “Ethnicity” is fluid and depends on context, incorporating the notions of a shared social, cultural, or religious background that is distinct and passed on between generations leading to a shared identity.[11] A range of definitions exists for “Culture,” which can be described as the repeated behavioral responses in society with social, religious, intellectual, and artistic influences.[12] For this review, the most commonly used terms in the literature “Ethnicity” and “Culture” will be viewed as synonyms.

This systematic review aims to investigate the relationship between ethnicity and the pain experience of cancer patients. At present, there are no reviews in this area of research in the literature, and results from this study will allow identification of barriers to pain relief, variations in pain severity, and differences in perception of cancer pain among ethnic groups. High social mobility within Europe has increased the likelihood that health care professionals will care for a more diverse population of patients with ethnic or cultural backgrounds different to their own. Further knowledge on the role of ethnicity on the pain experience will raise awareness of cultural differences so that treatment strategies can be adapted appropriately.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A systematic search strategy was developed by the author (Wingfai Kwok) to capture studies investigating the relationship between culture or ethnicity and the pain experience of cancer patients. The author (Wingfai Kwok) conducted the search on October 2013 in five online databases: (1) Medline (1946-2013), (2) Embase (1980-2012), (3) The Cochrane library, (4) PubMed, and (5) Psycinfo (1806-2013) using the following free text words in the title and abstract:

-

Cancer

-

Pain, Pain measurement, Analgesic, Analgesia

-

Ethnicity, Ethnic groups, Minority groups, Migrant, Culture, Cultural background, Ethnic background.

Truncated and wild card symbols were used where appropriate. A combination of 1 ∩ 2 ∩ 3 yielded 684 studies, and an additional seven studies were identified through hand searching of reference lists and citations of relevant articles. The author (Wingfai Kwok) and an independent researcher (Thakshyanee Bhuvanakrishna) discussed and developed the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review. The abstracts were then screened according to these criteria, if suitability of the article was unclear the full text was retrieved, and disagreement was resolved through discussion. Following a full text review and methodological quality assessment, 11 articles were identified for this review as shown in Figure 1. The search provided a mix of both quantitative and qualitative articles. In order to extract relevant information, a table was developed (Wingfai Kwok and Thakshyanee Bhuvanakrishna) to extract the key themes from each paper. Data was extracted from each paper independently and compared through discussion. This review presents a summary of the thematic analysis of the included articles, as shown in Table 1.

Search tree

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Culture and ethnicity are terms difficult to define, especially with rapid changes in worldwide demographics due to population mobility. This review will only include recent studies published during 01 January 1998-01 October 2013. As there were limited studies in the literature found in preliminary searches, both quantitative and qualitative studies will be included. The sample population to be included must be adults at least 18 years of age, suffering from any form of cancer, and experiencing cancer-related pain. The article must also describe direct comparisons between samples from at least two different cultural/ethnic backgrounds. As the experience of cancer pain is varied, we decided to include multiple outcome measurements in this review, such as the prevalence and severity of pain, health-seeking behavior, treatment outcomes, availability of treatment, patient and caregiver attitudes or behaviors, and barriers in accessing health care. We excluded narrative reviews, case reports, studies describing pain in non-cancer patients, studies not written in English, and studies describing cancer survivors.

RESULTS

From the 11 studies included in this review, two main themes were identified-the management of cancer pain and the perception of the pain experience. Six studies showed cultural differences in barriers to pain treatment[81314151617] and one study showed no difference.[6] Three studies showed cultural differences in symptom severity[678] and one did not.[13] Interestingly, two qualitative studies suggest that there are differences in the perception of pain and coping mechanisms between ethnic groups.[1618]

Management of cancer pain

A large meta-analysis showed the cultural differences in perceived barriers to cancer pain management between Western and Asian patients.[15] The review included 22 studies from the United States, Australia, Puerto Rico, Hong Kong, Korea, and Taiwan that used Ward's Barrier Questionnaire (WBQ). Asian cancer patients reported significantly higher barrier questionnaire scores (BQ score) compared to Western patients for concerns about cancer progression (weighted mean difference, WMD) = 1.32, 95% cumulative incidence, CI = 0.80-1.84, P < 0.0001), drug tolerance (WMD = 1.63, CI = 0.91-2.36, P < 0.0001), fatalism (WMD = 0.89, CI = 0.28-1.52, P < 0.0001), and total barrier scores (WMD = 0.82, CI = 0.36-1.28, P < 0.0001). A similar small study by Mosher et al., (2010)[8] examined barriers to pain management in a multiethnic sample of breast cancer patients using WBQ in the USA. The authors recruited 87 patients and showed that Spanish-speaking Latina patients had a significantly higher BQ score relative to Caucasians, but no significant differences were reported for Afro-American and Spanish-speaking Caucasian patients.

Bernabei and colleagues (2008)[14] analyzed data from the Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Drug Use via Epidemiology (SAGE) database, which contains data from patients in nursing homes across five states in the USA. From a sample of 13,625 elderly individuals diagnosed with cancer, the prevalence of cancer pain across all ethnicities was 29.4%. African-American patients were significantly less likely to have their pain recorded compared to the white reference population even after adjustment for language difficulties (odds ratio, OR = 0.55, 95% CI = 0.46-0.66). In addition, African-Americans had a 63% increased chance of being undertreated for their pain compared to whites (OR = 1.63, 95% CI = 1.18-2.26). A similar result was shown in a survey of first generation black Caribbean and white advanced cancer patients in three inner London boroughs.[17] The authors interviewed bereaved family and friends (respondents) of 69 patients. Black Caribbean patients were approximately seven times more likely to suffer from pain relative to white patients (OR = 6.9, 95% CI = 1.9-2.5, P < 0.003). There was no significant difference in the presence of pain during the last week of life between the two groups. Interestingly, there was a significant difference in respondent's perceptions of pain management. Among patients suffering from pain, a higher proportion of white patients receive treatment (2 = 4.22, 1df, P < 0.05) compared to blacks. A higher proportion of respondents for white patients also believed general practitioners “tried hard enough” to treat the cancer pain (2 = 9.00, 2df, P < 0.01) compared to black patients. There were no differences in the perception of pain control by hospital doctors.

Anderson et al., (2000)[13] investigated the pain intensity and attitudes towards analgesic medications using the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) in 108 African-American and Hispanic cancer patients and their physicians in the USA. The results showed that physicians underestimated the pain severity in 75% of Afro-Americans and 64% of Hispanic patients. Additionally, 28% of the Hispanic and 31% of Afro-Americans reported insufficient analgesia for their pain. Despite barriers for pain relief, a retrospective study of 980 Hispanic, white, and black cancer patients showed no difference in referral time (mean = 14.5 months) from first presentation at a cancer center to consultation at a specialist support service in the USA.[6] A qualitative study using four national online forums for white, Hispanic, African-American, and Asian cancer patients (n = 75) showed that all four ethnic groups expressed difficulty in communicating to caregivers about their pain with most Hispanic and African-American patients, stating this was due to language barriers.[16] Women in all ethnic groups expressed the view they were more disadvantaged in accessing pain management compared to men.

The pain experience

There is evidence for cultural differences in the cancer pain experience. A significantly greater proportion of Hispanics (50%) and blacks (49%) presented with severe pain at first consultation at a cancer center compared to white (33%) patients.[6] After adjustment for age, sex, stage of cancer, and comorbidities, both Hispanic and black patients were nearly twice as likely to report severe pain relative to white patients (Hispanics: OR = 1.92, 95% CI = 1.21-3.10, P < 0.001; blacks: OR = 1.90, 95% CI = 1.24-2.93, P < 0.001). Following referral to a specialist support center, whites were the only group to show a significant improvement in severe pain relief. Similarly, Mosher et al., (2011)[8] showed that black and Caucasians reported lower average Brief Pain Inventory scores compared to Latina patients who spoke Spanish. In a recent internet study (n = 388) of different ethnic groups, the severity of cancer pain, physical function impairment, and cancer-related symptoms were stratified into three progressive clusters.[7] Asian Americans reported lower pain scores in cluster 2 (moderate pain) compared to Hispanics and African Americans; there was no ethnic differences in the other symptom clusters. Finally, a retrospective audit of patients diagnosed with esophageal and gastric cancers (n = 244) at City Hospital, Birmingham[19] showed that a greater proportion of Asian (43%) and black (46%) patients described abdominal pain compared to the Caucasians (22%). In contrast to these results, the study by Anderson and colleagues (2000)[13] showed no difference in BPI scores between Hispanic and African-American cancer patients, but no reference Caucasian population was described.

Perhaps, most interesting are the differences in cultural perception of cancer pain. Themes from an online forum suggest ethnic minorities believe that there is a negative stigma associated with cancer, and increasing pain is equal to worsening of their condition. Subsequently, patients would refuse to talk about their cancer leading to normalization of their pain.[16] Asian patients in particular would hide their pain, as it was often viewed as bad karma. Strong religious beliefs helped the majority of ethnic minority patients face cancer, minimalizing their pain experience. In contrast, white patients seek to control their pain through Western medicine and actively pursue potential therapeutic options, whereas ethnic minorities tended to rely on natural modalities for pain management. Similarly, a qualitative study using patient interviews (n = 45) identified different views among black and Caucasian patients with advanced cancer.[18] Black patients identified pain as a “test of faith” to affirm and strengthen their religious beliefs as well as “a punishment” for bad deeds. Common to both groups were views of pain as “an enemy” and “a challenge” to be overcome. Lastly, a study analyzed the data from a large database of responses from the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLC-C30 questionnaire to investigate the effect of pain on QoL in different cultures.[20] The pain subscale had a greater influence over the QoL score for patients in the UK compared to other European countries; the authors suggest that culture may influence the effect of cancer pain on QoL.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this systematic review was to investigate the relationship between ethnicity and the pain experience of cancer patients. The results were broad and two key themes were identified. Firstly, six studies showed that there are cultural differences in barriers to pain treatment. Asian and Spanish-speaking Latina patients report higher barrier questionnaire scores compared to Western patients, but not Afro-Americans.[815] Patients who perceive high barriers to pain management underuse analgesics[2122] and this may explain the high prevalence of undertreated cancer pain among American Asian cancer patients.[23] Black patients in the USA are significantly less likely to have their pain recorded, and a similar non-significant trend is noted in other ethnic groups despite adjustment for language differences.[14] Poor pain assessment may be due to language difficulties in communicating with caregivers,[1624] or due to underestimation of pain severity from health care professionals.[13] Influences from a patient's cultural background can also affect the willingness for a patient to self-report pain, as there is evidence which shows there is a greater reluctance among black and Hispanic patients.[25] There is little evidence describing barriers to accessing health care. Although Hispanic and black patients received insufficient analgesics compared to white patients,[13] there was no difference in referral time from first presentation to consultation at a specialist cancer support Center.[6] It is difficult to rule out the possibility of prejudice and racism towards ethnic patients as a potential barrier to accessing pain relief.

Secondly, there is evidence for variations in the pain severity among ethnic groups. There is evidence for a greater prevalence of pain among Hispanics, blacks,[6] and Spanish-speaking Latina patients[8] compared to white cancer patients. Additionally, Asian Americans report lower levels of moderate pain compared to other ethnicities[19] but there is no difference in BPI scores between Hispanic and African-American cancer patients.[13] Although each study identified differences between ethnic groups, they shared a common Caucasian reference population. This suggests pain severity is higher in ethnic groups compared to white cancer patients. This may be due to barriers in accessing health care and poor attitudes to disease management, leading to a greater proportion of ethnic patients suffering from advanced stages of cancer, which is correlated with a greater pain experience.[26] Ethnicity is often correlated with a low socioeconomic status; multiple studies have shown that these are population groups at risk of poor pain outcomes.[2728] Additionally, high-income cancer patients experience less pain[29] compared to low-income individuals.[30] The differences in cultural perception of cancer sheds light on how individuals conceptualize cancer pain, which is perhaps the most important determinant of the pain experience which is subjective in nature and dependent on multiple influences. Normalization of cancer by Asian patients may adversely affect health-seeking behavior, leading to greater pain severity. The shared belief of cancer pain “as an enemy” and “a challenge” between ethnic groups represents common ground, and may be utilized to develop strategies to encourage patients to seek cancer treatment.

There are five main limitations of this study. First, we could not rule out publication bias from this review. Secondly, study heterogeneity made it difficult to compare each ethnic group with the same reference population, heightened by the lack of relevant articles in the literature. Third, we were not able to differentiate between first and second generation immigration status, and thus did not account for social mobility between countries. Fourth, the complexity in defining ethnicity may have led to type 1 error in the results of each study. Lastly, the omission of non-English language papers from this review as an exclusion criterion may have missed important findings in relation to culture and pain perception. The main strength of this review is that it is the first systematic review investigating the relationship between ethnicity on the pain experience of cancer patients. In light of the cultural differences identified in this review, further research should focus on strategies to improve access to cancer pain treatments for ethnic patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Rachel Burman and Jonathon Koffman (Cicely Saunders Institute) for their support and help with this manuscript.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- The association between pain and depression, anxiety, and cognitive function amongst advanced cancer patients in the hospice ward. Korean J Fam Med. 2013;34:347-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early referral to supportive care specialists for symptom burden in lung cancer patients: A comparison of non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic blacks. Cancer. 2012;118:856-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Symptom clusters among multiethnic groups of cancer patients with pain. Palliat Support Care. 2013;11:295-305.

- [Google Scholar]

- Self-efficacy for coping with cancer in a multiethnic sample of breast cancer patients: Associations with barriers to pain management and distress. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:227-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is the experience of cancer-related pain shaped by ethnicity or cultural background? Eur J Palliat Care. 2011;18:130-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Minority cancer patients and their providers: Pain management attitudes and practice. Cancer. 2000;88:1929-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. SAGE Study Group. Systematic assessment of geriatric drug use via epidemiology. JAMA. 1998;279:1877-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Meta-analysis of cultural differences in Western and Asian patient-perceived barriers to managing cancer pain. Palliat Med. 2012;26:206-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- A national online forum on ethnic differences in cancer pain experience. Nurs Res. 2009;58:86-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Symptom severity in advanced cancer, assessed in two ethnic groups by interviews with bereaved family members and friends. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:10-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cultural meanings of pain: A qualitative study of Black Caribbean and White British patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med. 2008;22:350-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of ethnicity on the presentation and management of oesophageal and gastric cancers: A UK perspective. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:996-1000.

- [Google Scholar]

- The relationship between overall quality of life and its subdimensions was influenced by culture: Analysis of an international database. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:788-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Barriers to pain management in a community sample of Chinese American patients with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:665-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Barriers to the analgesic management or cancer pain: A comparison of attitudes of Taiwanese patients and their family caregivers. Pain. 2000;88:7-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1985-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dimensions of the impact of cancer pain in a four country sample: New information from multidimensional scaling. Pain. 1996;67:267-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- The influence of ethnicity and race on attitudes toward advance directives, life-prolonging treatments, and euthanasia. J Clin Ethics. 1993;4:155-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10:19-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethnic similarities and differences in the chronic pain experience: A comparison of African American, Hispanic and white patients. Pain Med. 2005;6:88-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Population-based survey of pain in the United States: Differences among white, African American, and Hispanic subjects. J Pain. 2004;5:317-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Net worth predicts symptom burden at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:827-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pain and quality of life among long-term gynaecological cancer survivors: A population-based case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:1510-6.

- [Google Scholar]