Translate this page into:

Colorful Screams of Silent Emotions: A Study with Oncological Patients

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Art, as a product of human behavior, is the expression of emotions from inner states and may provide catharsis, purification, and release. Several branches of art, most notably music, dance, and painting, can be used for treatment purposes, especially in the case of psychological disorders. Cancer, which is defined as uncontrolled cell growth, has been an important health issue throughout history, but the recent increase in its frequency has made it one of the most significant public health problems. Both the physiological distress the disease subjects the body to and the accompanying emotional distress are important factors to be considered in cancer treatment.

Aims:

In this study, the role of art in expressing emotions of oncological patients was investigated.

Materials and Methods:

During the treatment period, patients were interviewed about their experiences, feelings, expectations and perceptions. The picture was used as an expression of emotions.

Results:

Communication between the patient and doctor is one of the most important elements in the treatment process, and it has come to the fore in branches of medicine, such as oncology, because of its positive contribution to treatment compliance. In general, the study showed a pronounced positivity and expectations on the part of patients from the hope-life-healing process rather than oncological treatment.

Conclusion:

In this study, we aim to demonstrate how the artistic expression of emotions, in particular, through painting, has a positive effect on healing, hope, and the interactions between cancer patients under oncological treatment and medical professionals.

Keywords

Art therapy

cancer

hope life

oncological treatment

painting

INTRODUCTION

Art exists in every period of human history and has the power to influence emotions and thoughts. As a branch of visual arts, painting helps us make sense of a person's inner life by creating an outlet for its expression.[1] Cancer affects a person's life at multiple levels, including physical, psychological, social, and spiritual levels, and causes significant life changes.[2] Beginning with patient's body, it affects the whole existence from family relations and social environment to work and livelihood as well as feelings and beliefs.

According to the estimates of the World Health Organization, a total of 14 million people worldwide have cancer, and the number of new cases diagnosed annually will be 20 million by the year 2020.[3] Ancient Egyptian papyrus remains dated back to 1500s BC depicted cancer as a crab killing people between its claws, and Hippocrates used the terms karkinos and karkinomas.[4] Cancer, which is defined as uncontrolled cell growth in the body, involves challenging treatment procedures, such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Although the response to a cancer diagnosis varies with each individual, Kübler-Ross described five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.[5] In the process of fighting this difficult illness, it is important to accept it first and then to adapt to a long and challenging treatment process. After all, the patient faces a threat that is alive, grows, and continuously transforms. In cancer, both the body and the mind are subject to devastating effects of oncological treatment procedures in addition to the disease itself.[6] Following the initial diagnosis, both the patients and their families have to face the cold reality of death, something they always knew but never cared much about before. In this very human process, it is important that both the patient and family have access to psychological support.

Oncology is a medical discipline where the bond of trust and solidarity between the doctor and the patient bears special importance. As specialists of oncology, we usually have a chance for long conversations with patients and their families. In the treatment process, it is essential to provide social support, make time for the patient and family, inform them, get to know the patient, and address their feelings in addition to making use of available treatment procedures. We know that patient–doctor communication increases treatment compliance.[7] Painting is a branch of art, whereby people can express their emotions with colors and shapes without the need for words, and this art form can also be used for psychological relief and treatment purposes.[89] In this study, we aimed to use the art of painting to reveal what patients felt but could not express in the process of diagnosis and acceptance of cancer as well as their expectations from the treatment modality. Painting as a nonverbal expression of emotions can help us understand patients’ view of cancer, their hopes and expectations, and their responses of fear, denial, helplessness, and despair. Painting may represent a chance to get to know the patient better through their feelings about the treatment process as reflected in patients’ paintings. With an appropriate use of data, the art of painting can contribute positively to the clinical understanding of the oncological treatment process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Twenty patients admitted to the University Clinic of Radiation Oncology in the year 2017 with a cancer diagnosis who received oncological treatment (surgery and/or chemotherapy) and were still in radiotherapy were included in this study. The study was explained to patients, and written informed consent was obtained. During the course of their radiotherapy sessions, the patients were interviewed about their experiences, feelings, expectations, and perceptions. Age, gender, diagnosis, and stages of cancer were all recorded. In addition, patient feelings in connection to cancer, expectations, and fears about oncological treatment, hope and despair, pain, and negative experiences were also recorded. After the interview, patients were asked to express their feelings through painting. Patients’ emotions found their way to the canvas with the aid of a painter-academician.

RESULTS

Following the interview, the paintings by 20 patients were evaluated based on the consideration of their affective states, treatment expectations, and feelings. Three paintings were selected from each group. Then, all paintings were classified into five categories: treatment; psycho-oncological emotions, such as denial, ignorance, and loneliness; positive changes in perception with influence of treatment; affective states upon receiving information; and hopes of recovery of the palliative patient as reflected on paintings.

-

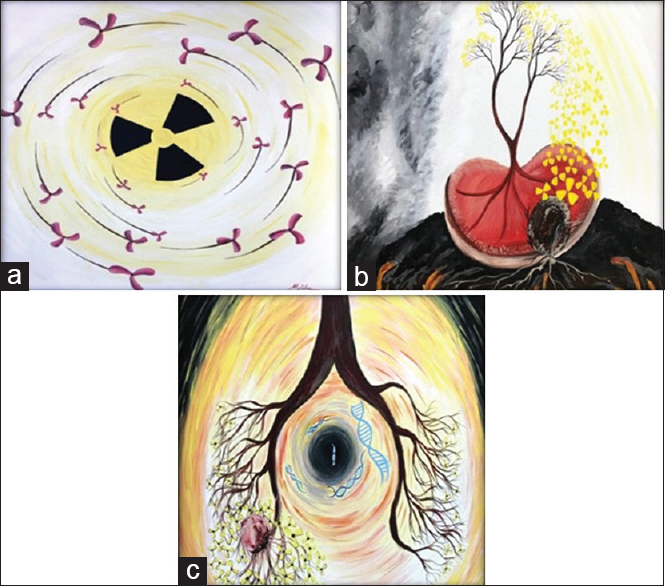

Group 1: The thoughts of patients on their radiotherapy and chemoradiotherapy procedures and on the outcome of treatment [Figure 1a-c]

-

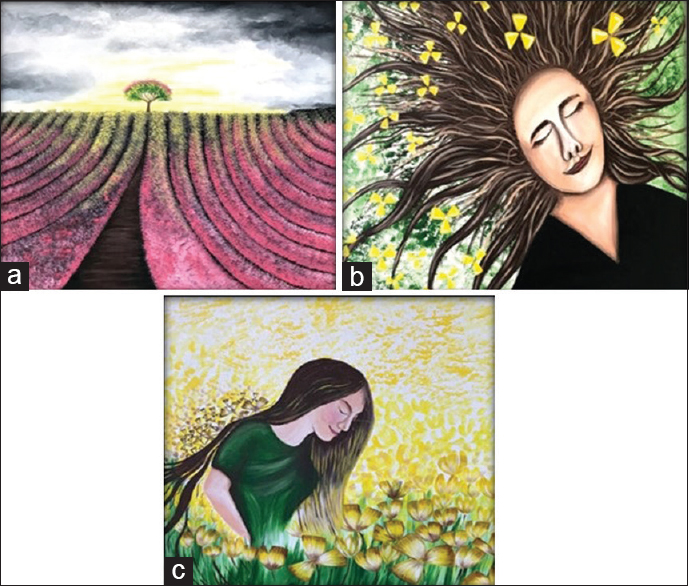

Group 2: Psycho-oncological feelings, such as denying or ignoring the disease, accepting it, and loneliness, as reflected on the paintings by patients with cancer diagnosis [Figure 2a-c]

-

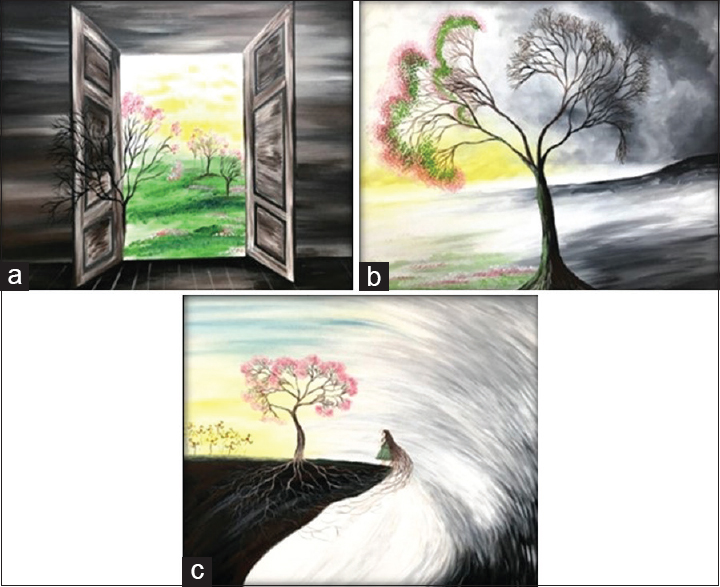

Group 3: Paintings show the positive shift in perception from distress during the stages of diagnosis and treatment to the excellent response to radiotherapy [Figure 3a-c]

-

Group 4: How patients felt after being informed about the treatment modalities and prognosis [Figure 4a-c]

-

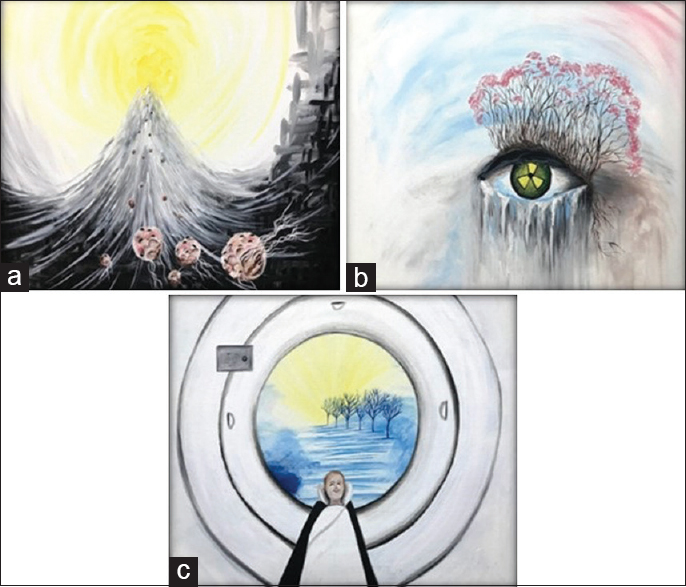

Group 5: Emotions experienced by extensive metastatic patients following palliative treatment were expressed through art. The hopes patients invested in treatment and positive outcomes as expressed in a decrease in their complaints, symptoms, and pain during the treatment process all found their way into these paintings regardless of the stage of illness [Figure 5a-c].

- Patient paintings depicting the processes of radiotherapy and chemoradiotherapy. (a) An 82-year-old female patient suffering from a painful and degenerative meningioma depicts the therapy room and the device delivering radiotherapy. “I feel, therefore I am” (Andre Gide). (b) A 42-year-old patient with a diagnosis of primary renal cell carcinoma depicts the dream of recovery following radiotherapy due to relapse after all primary treatment. “The difficult is what takes a little time; the impossible is what takes a little longer” (Fridtjof Nansen). (c) A 55-year-old small cell lung cancer patient in concomitant chemoradiotherapy paints the dreamed healing process. “If you can dream it, you can do it” (Walt Disney)

- Following a cancer diagnosis, psycho-oncological emotions of denial, ignorance, acceptance, and loneliness on canvas. (a) This 19-year-old patient diagnosed with soft-tissue sarcoma of the extremities completely ignored the condition despite the indications before and after treatment (surgery-radiotherapy-chemotherapy). “Good things come to those who believe, better things come to those who wait and the best things come to those who don’t give up” (Anonym). (b) A 37-year-old breast cancer experienced despair due to organ loss with right modified radical mastectomy but still turned to healing and life as depicted. “At some point, you just have to turn around and face your life head on” (Chris Cleave). (c) A 72-year-old patient receiving hormone therapy and radiotherapy for prostate cancer depicts his loneliness in a nursing home following the illness. “One person's loneliness is the escape of the sick; another's loneliness is the escape from the sick” (Friedrich Nietzsche)

- Rejoicing after a difficult treatment process. (a) A breast cancer patient depicts hardship and challenges of the process from diagnosis to treatment and follow-up. “What teaches us to appreciate the good in life is the troubles we face” (Goethe). (b) A 27-year-old patient with low-grade brain cancer depicts the happiness and joy of regaining hair after multiple-field radiotherapy. “Every happiness is bought with a suffering” (Alexandro Manzoni). (c) A patient depicts the feeling of the patient regaining ability to walk after surgery and radiotherapy for relapsed thoracic ependymoma. “Most people don’t appreciate what they have until they lose it” (Sophocles)

- Emotions of patients who received detailed information on treatment modalities and prognosis. (a) A 48-year-old patient with locally advanced rectal cancer depicting emotions of the pretreatment stage and following the surgery performed without colostomy thanks to a successful neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. “When the world says ‘Give up!’ hope whispers: ‘Try it one more time from the movie” (Shawshank Redemption). (b) Depicting the conflict of hope and despair experienced by an operated lung cancer patient before adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. “For all hope is hidden within despair” (Al-Ghazali). (c) Depicting how a glioblastoma patient feels after receiving information on the prognosis. “Don’t look back, that's not where you are headed!” (Confucius)

- Emotions of patients with extensive metastasis following palliative treatment. (a) A 57-year-old male patient with malignant melanoma metastasizing to the bone, brain, and lungs depicts feelings following immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. “Hope the following page. Do not close the book” (Edmond Jabès). (b) A 29-year-old breast cancer patient with metastasis to the liver and local relapse depicting feelings prior to palliative radiotherapy for unrelieved pain. “Each beginning has an end” (Shakyamuni Buddha). (c) A 55-year-old patient with metastatic lung cancer depicting feelings of relief after painful metastasis to the bone was stopped by radiotherapy. “Good deeds put a smile of happiness on another's face” (Prophet Muhammad PBUH)

In the course of the study, we observed that patients mostly used yellow, blue, pink, and dark colors. The color yellow symbolizes illness, whereas dark colors are related to fear and despair. Blue indicates a desire for relief and peace, and pink represents inner hope and energy. Patients who were aware of the diagnosis of cancer represented their joy and happiness after the treatment by making smiling faces on the canvas. They painted tree figures as an expression of their wish to hold on to life, and the frequent floral figures were an expression of their hopes. In general, the study showed a pronounced positivity and expectations on the part of patients from the hope-life-healing process rather than oncological treatment.

DISCUSSION

No burden is heavier than agony left unexpressed. Therefore, expressing emotions brings relief, which is especially important for the oncological patient going through the difficult process of cancer treatment. It is difficult to categorize adult emotions since human responses are more complex than we want to think. Occasionally, speech and gestures fall short of an accurate expression of what we feel, and we may want to complement these expressions with visual expression, for instance, by painting. The art of painting allows us to express difficult experiences and complex feelings that we cannot express with words. Colors, the silent scream of our emotions, come together on the canvas to lend meaning to things, we find it difficult to say and give us the joy of expressing our emotions.

Cancer is one of the most important medical problems of our age. The difficulty of diagnosis and treatment as well as the emotional trauma experienced in the process add to the burden of the patient. The improvement in oncological treatment and the increase in treatment success rates give us more hope than ever, but we are still far from achieving the desired goals. Studies suggest increased rates of anxiety, depressive mood, impaired social interaction, sleep disorders, and fatigue in cancer patients.[1011] In addition, patients with less social support have higher levels of anxiety and cortisol.[12] If the individual cannot attain a heightened awareness or healthy outlook about the facts as required at critical turns in life, this may exacerbate the problems. More often than not, these problems cannot be expressed verbally. This lack of expression and communication is an adverse factor not only in terms of patient's psychological well-being but also for the treatment process. We know that patients believe in and commit to treatment only when they develop a genuine bond of communication and trust with their doctors.

Visual arts therapy, which forms a language of its own with lines, colors, and shapes, is a practice that brings relief to everyone from childhood. The first to draw an analogy between words and images was Simonides (556-469 BC) who defined painting as “silent poetry.” Horace wrote in his Ars Poetica that “Ut pictura poesis” (as is painting so is poetry).[13] Once art's importance in human life was established, the question was whether it could be used in the treatment of diseases. In the early 1900s, European psychiatrists, Emil Kraepelin and Karl Jaspers observed that drawings were an expression of patients’ psychological disorders. Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, included artistic concepts in clinical studies.[114] Today, we know that art therapy can be used to support a positive individual development but also to resolve conflicts, alleviate physical and psychological conditions, solve problems, cope with stress, and help the process of diagnosis and treatment.[15] As a means of communication since the dawn of humanity, painting is now successfully used to bring catharsis and comfort to patients. In 1969, visual arts therapy was accepted as a method in health care by the American Art Therapy Association.[1] Child psychiatrists have always made use of paintings as an expression of the child's emotions.[16] Paintings and drawings by patients are used in the processes of diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up in several medical specialties, most notably psychiatry.[1718] Therefore, the question is, given that its positive psychological effects are established, can we use art with oncology patients? With this idea as our starting point, we provided oncology patients (receiving chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy) a means to express their feelings and thoughts through art with the aim of observing its influence on the process of hope-life-healing and treatment expectations.

Following verbal communication, oncology patients were asked to paint under the supervision of a painter-academician. An examination of their work showed that patients did not lose hope in the cold face of cancer, and they maintained positive expectations about treatment. Many researchers studied the influence of art in the process of oncological treatment. Bar-Sela et al.,[19] Götze et al.,[20] Wood et al.,[21] Monti et al.,[22] Thyme et al.,[23] and Puig et al.[24] demonstrated its positive effects on oncology patients. In a 2016 study with 55 patients, Nainis et al.[8] showed that cancer patients experienced significantly lowered levels of pain, fatigue, and anxiety after art therapy sessions. An outcome of these findings is the tendency to design oncology clinics as spacious and relaxing places using soft and warm wall colors and decorating the interior spaces with paintings.

Every human experience has the mark of time and space.[25] In paintings, the individual becomes one with the environment and the experience. Our study documents all patients’ experiences in the form of paintings that depict everything from their feelings about the treatment room and device to the tears in their eyes. Figure 1a was painted by a patient receiving volumetric arc therapy (VMAT) for atypical meningioma. The room and the VMAT device rotating overhead to deliver radiation are interpreted as small radiations flying in the air.

Most of the time, a remarkable aspect about these paintings was patients’ ongoing hope that they would benefit from treatment. In paintings with lots of yellow, blue, pink, white, gray, and dark tones, we observe doors opening to the light, blossoming trees, and bright skies with sunshine. Figure 1c, which was made by a patient receiving concomitant chemoradiotherapy for small cell lung cancer, is full of hope and shows the dreamed recovery. For patients depicting their lungs as tree branches, healing comes with refoliation and blossoming.

In Figure 2a, the denial of the disease is clearly observed. The patient rejects looking at a problem as heavy as cancer and rides on the swings they created in their own inner world. Figure 2b is by a patient who underwent breast cancer surgery and depicts how the patient eventually embraced life for all the distress brought along with organ loss and the inner conflicts of denial and acceptance. Figure 3b shows the happiness of a patient after regrowth of hair, which was lost given that the dose of multiple-field radiotherapy delivered in the treatment of low-grade brain cancer affected hair follicles. Figure 3c is a painting with similar features and was made by a patient on their way to recovery.

The patient who painted Figure 4a faced the possibility of a colostomy due to rectal cancer. The process that began with fear and distress and the relief experienced with the information that surgery would be possible without colostomy thanks to a successful neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy is depicted as a window opening in the darkness. Following new information on the prognosis of glioblastoma, another patient still depicted himself on the brink of a cliff, but with his face turned toward a bright space lined with trees, as an expression of a will to live.

The tears in Figure 5b are the unrelieved pain of a young patient diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer, whereas the pink tiny flowers blooming on the eyelid represent hope embodied in the expectations from palliative radiotherapy.

Psychiatric disorders can be observed in cancer patients similar to other patients.[26] Due to withdrawal and lack of communication, psychiatric problems may be easily missed in cancer patients, leading to underdiagnosis and undertreatment.[27] The relationship between affective states, such as depression and cancer, are examined in various studies. In some of these studies, depression was associated with cancer progression, while it was associated with survival in other studies.[28] This finding suggests that human experience can cover a wide range of emotional states and what really matters, especially in a negative affective state, is communication. In the challenging processes of diagnosis and treatment, cancer patients need healthy communication with family and friends as well as doctors. Emotional expression through art may help reveal the whole spectrum of patient emotions, including depression. The comforting power of the art of painting combined with a positive patient–doctor communication becomes important in maintaining hope and improving mood, which can subsequently contribute to a better survival rate and life quality in cancer patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Consequently, cancer is a systemic disease requiring a tough fight as the body is subject to an invasion by its own cells. Patients have to shoulder both physiological and psychological burdens that may have adverse effects on the treatment process. In the course of this struggle, patients experience varying emotions and affective states. Defining these emotions and communicating them properly can bring positive results. The art of painting appears as a perfect medium of communication when words do not suffice. In the long and formidable road of treatment, there is occasionally nothing left to do. At such times, our last duty as doctors is to simply be there for the patient and provide guidance where necessary. At such moments, it may be crucial to encourage the patient to try and regain hope. Communication is how we express ourselves. Communication can be verbal, but it can also occur through paintings or music. Just as love grows larger by sharing, the feelings of distress and fear can dissolve in a similar manner. In conclusion, we suggest that the art of painting should be considered as an integral part of oncological treatments.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Recep Tayyip Erdogan University, Coordination Unit for Projects of Scientific Research, Grant number THD-2018-894.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Melike Nur Uzunoglu, a painter and academician, who helped in the process of drawings.

REFERENCES

- The connection between art, healing, and public health: A review of current literature. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:254-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nursing intervention to increase hope in cancer patients. J Clin Nurs. 1998;7:19-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- What is the best way to help caregivers in cancer and palliative care? A systematic literature review of interventions and their effectiveness. Palliat Med. 2003;17:63-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- A brief history of cancer: Age-old milestones underlying our current knowledge database. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:2022-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Questions and Answers on Death and Dying: A Companion Volume to On Death and Dying. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2011.

- [Google Scholar]

- Frequency and correlates of posttraumatic-stress-disorder-like symptoms after treatment for breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:981-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient trust in the physician: Relationship to patient requests. Fam Pract. 2002;19:476-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relieving symptoms in cancer: Innovative use of art therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31:162-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Mature Mind: The Positive Power of the Aging Brain. New York: Basic Books (AZ); 2005.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: A follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:39-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial concerns and interventions for cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5132-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Host factors and cancer progression: Biobehavioral signaling pathways and interventions. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4094-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The use of photography in psychiatric rehabilitation: A pre-project. J Psychiatr Nurs. 2010;1:121-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Listening to children with communication impairment talking through their drawings. J Early Child Res. 2009;7:244-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Catching life: The contribution of arts initiatives to recovery approaches in mental health. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2007;14:791-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Art therapy as a tool for social change: A conceptual model. In: Kaplan FF, ed. Art therapy and social action. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2007. p. :21-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Art therapy improved depression and influenced fatigue levels in cancer patients on chemotherapy. Psychooncology. 2007;16:980-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Art therapy for cancer patients in outpatient care. Psychological distress and coping of the participants. Forsch Komplementmed. 2009;16:28-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- What research evidence is there for the use of art therapy in the management of symptoms in adults with cancer? A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2011;20:135-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- A randomized, controlled trial of mindfulness-based art therapy (MBAT) for women with cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15:363-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Individual brief art therapy can be helpful for women with breast cancer: A randomized controlled clinical study. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7:87-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- The efficacy of creative arts therapies to enhance emotional expression, spirituality, and psychological well-being of newly diagnosed Stage I and Stage II breast cancer patients: A preliminary study. Arts Psychother. 2006;3:218-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial intervention effects on adaptation, disease course and biobehavioral processes in cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30 Suppl:S88-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric disorders and mental health service use in patients with advanced cancer: A report from the coping with cancer study. Cancer. 2005;104:2872-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Decrease in depression symptoms is associated with longer survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a secondary analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:413-20.

- [Google Scholar]