Translate this page into:

Who Can Provide Spiritual Counseling? A Qualitative Study from Iran

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background and Aim:

Given the increased prevalence of mental illnesses in recent years, many therapists and researchers use spiritual counseling (SC), which is one of the spiritual interventions. However, unfortunately, the use of this intervention by the therapists is nonscientific because the ambiguities of this issue are high in the mental health field of Iran. The aim of this study is to survey the following most important challenges: what groups are qualified to provide SC, what kind of knowledge should be known by suitable individuals, who can train spiritual counselors, what they should teach, and what teaching methods should be used.

Methods:

The present conventional qualitative content analysis used deep semi-structured interview to collect data from the view of stakeholders. A total of 15 people were selected through purposive sampling. After transcription of the interviews, the data were analyzed based on the Graneheim and Lundman model.

Results:

Results obtained from data analysis covered five main themes including SC candidates, general conditions, sciences required, SC curriculum, and spiritual counselors' training method.

Conclusions:

The present study has answered to the most basic questions in SC scope. Since spiritual services are rooted in our culture and religion, native guidelines should be created for them as soon as possible through conducting similar qualitative researches. Furthermore, it is worth considering teaching and training case in this scope to make spiritual service providers concern about solutions to promote these services.

Keywords

Education

Iran

mental health

qualitative research

spiritual counseling

INTRODUCTION

Mental illnesses can negatively affect the life and well-being of millions of people, affecting all of the health scopes. According to the estimation provided by the World Health Organization (WHO), one out of four individuals suffers from mental disease during his/her lifetime.[1] Moreover, outbreak of mental diseases in Iran has recently increased so that this statistic shows higher rates compared to other countries. This indicates the necessity for addressing the effectiveness of interventions and adopting some solutions to handle such conditions.[2] On the other hand, spiritual interventions have become attractive for many people, and effectiveness of these interventions on various groups of physical-mental patients and healthy individuals has been proved.[34567]

Spiritual counseling (SC) is one of the spiritual interventions,[8] in which a counselor helps the patient with his/her problems, with emphasis on his/her spirituality, searching through spiritual issues. SC emphasizes on some techniques such as pray, forgiveness, serving, daily notes, book therapy, worshipping, and spiritual imaging.[9] Numerous studies have confirmed the effectiveness of this counseling in changing inefficient attitudes.[1011]

One significant issue in SC case associates with individuals who provide these services because specialty and skill of them in this field have a considerable effect on the quality of presented services.[412] Reviewing various studies on those who are allowed to provide such services revealed two results: (1) difference in SC service providers in different countries and (2) lack of scientific study on this field in Iran and presence of nonscientific and personal works on this subject.

SC services are done by three groups of experts in different countries. For instance, numerous studies have pointed to the role of pastoral counselors and religious experts in providing these services.[5] Moss and Snodgrass conducted a study on cancer patients and found that health providers should introduce these patients to a pastoral counselor who is expert in religious cases since the minds of these patients are occupied with their religious beliefs.[1213] In addition, Memaryan et al. mentioned the vital role of religious experts in presenting spiritual interventions in a guideline for cancer patients.[14] Besides religious experts, some studies have mentioned mental health service providers and counselors as individuals suitable for providing SC services. In fact, since the majority of clients have their own religious or spiritual worldview, the counselor should encourage the client to express his/her spiritual issues when making treatment relation with him/her because they are interested in speaking about this topic with counselor when they feel annoyed.[1516] The third category of studies addresses the main role of health service providers such as nurses in providing counseling to patients with physical and mental illnesses in hospital. Since nurses play a crucial role in making mental patients calm and supporting them and since nurses make relationship with patients, they can be good options to present SC for individuals with psychological problems who are hospitalized.[917]

It is essential to reflect on some other questions even after selecting suitable individuals for SC providing: what sciences should SC providers know? Who should teach them? and How should be these teachings? Hence, teaching methods for spiritual counselors are other challenges in SC scope. Reports show that many of the mental health experts are not adequately trained and experienced in this field, so they cannot solve spiritual and religious issues of clients and these needs remain unsolved.[1618] Despite the medical and physical health scope covering directions and protocols about spiritual cares for patients,[14192021] few native guides exist to help patients in case of mental health and answer these questions.[22]

Accordingly, solving these challenges and preparing instructions in this field in order to promote Iranian people health-care system are so important steps.[23] Since spirituality is a culture-oriented concept[24] and its definition subjects to various factors such as ethnicity, living environment,[25] cultural background, and religious beliefs,[26] this case should be addressed in each country and culture separately. Reviewing studies, we did not find any Iranian or foreign scientific references which have addressed this issue in mental health scope in Iran. Hence, a study on these topics contributes to promotion in this field.

METHODS

This was a qualitative study conducted based on the conventional content analysis method and used deep semi-structured interview to collect data from the view of stakeholders. The Statistical Society of Research comprised all of psychologists, psychiatrists, counselors, and chaplains with academic education in the field of mental health, patients with mental illness and their families, healthy individuals, and organizations which provide mental health services. We employ the 32-item Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist to describe research methodology. Criteria in this checklist were designed for qualitative studies which use interview or focus groups as instruments helping researcher to report significant parts.[27]

Research team

All interviews were conducted by the first author of this research. The author was an MA student in Mental Health at the time of study. In addition, the author was trained by professors who were experienced in conducting qualitative studies (items 1–5 in COREQ checklist). To set time for interviews, some participants received call contacts and some of them emails. In addition, research subject, objectives, and identity of author were given in contacts and emails (items 6–8 in COREQ checklist).

Participants

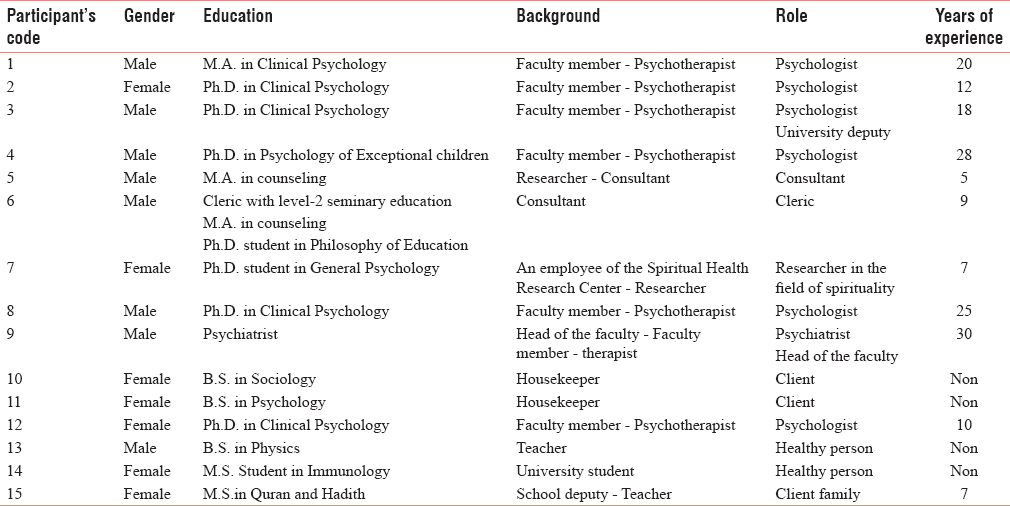

Purposive sampling method was used in this study. All interviews were conducted face to face without the presence of any other person in the interview. A total of 19 interviews were carried out and four interviews dropped out; also, nine members had not enough time to participate. Interview location of ten members was in their workplace, three members in clinic, and two members at home. All of the environments were prepared in terms of calmness. Of 15 participants, 8 members (53.3%) were male and 7 members (46.7%) were female. Table 1 indicates details about participants (items 6–8 in the COREQ checklist).

Data collection

Data were collected by deep semi-structured interviews. Interview questions were designed based on research objectives, reviewing texts, and consulting with three experts in spiritual health scope. Some questions were as follows: in your opinion, who is qualified to provide SC in mental health field? What sciences should be known by spiritual counselor? Who and how should teach spiritual counselor? Notes were taken during interview. Voice of interviewees was recorded and then inserted into the computer at the first opportunity. Each interview was conducted just once taking 14–91-min time. Interviews continued until saturation and no new code was found (items 17–22 in the COREQ checklist).

Data analysis

Content of each interview was implemented as analysis unit and then analyzed within five steps based on the Graneheim and Lundman model: (1) texts were read several times to understand general concept; (2) the text was divided to meaning units including concepts and meanings extracted from interviews' texts; (3) at this step, codes are labels on meaning units then codes were shortened keeping their main core; (4) codes were arranged based on their content similarities and created categories; and (5) ultimately, themes were created as bases for similar contents in categories. Since qualitative analysis requires a circular process, we looked backward several times to complete steps.[28] The initial content of interviews and results was not addressed by the participants, but the researcher considered her notes and opinions after each interview and the whole process was done by one person. In addition, data management was done manually without using software. To clarify codes, categories, and themes, direct quotations of interviews have been presented in results (items 23–32 in the COREQ checklist).

Data rigor and trustworthiness

Besides addressing items of the COREQ checklist, rigor and trustworthiness of data were examined using options below based on the Guba and Lincoln's[29] criteria: (1) long-term involvement with researcher immersion in research subject and process; (2) in revising by colleague, coding was done by the main author and then external check of codes was implemented by the corresponding author and some codes were corrected. In addition, after performing steps 4 and 5 of analyses by the first author, the corresponding author revised them. Other authors also monitored all steps and gave their opinion if necessary; (3) triangulation of data resources was done to review the opinion of stakeholders (psychologist, chaplain, client, etc.) through interview; and (4) Seeking opposed evidences led to comprehensive description of subject with purposeful sampling on individuals who may suggest opposite views.

Ethical considerations

Data of this article were extracted from dissertation approved and funded by the Research Council of Iran University of Medical Sciences under the ethical code IR.IUMS.REC 1395.9411704008 (contract number: 96-02-185-30773). The interviewer gave a brief explanation about the research objectives to participants; then, informed consent form was given then participants initiated interview based on ethical principles. Some of these principles included possible exclusion at each step, information confidentiality, and anonymous data release.

RESULTS

Results obtained from data analysis covered five main themes including SC candidates [Table 2], general conditions [Table 3], sciences required [Table 4], SC curriculum [Table 5], and spiritual counselors' training method [Table 6].

SC candidates is the most important theme extracted from data analysis consisting of the three following categories [Table 2].

Psychologists and counselors

This category indicates one of the main groups suitable for SC providing. Codes in this category describe specific conditions of this group that are required for SC.

Religious experts (chaplains)

This category was also mentioned by the majority of the interviewees as suitable SC providers. Codes in this category demonstrated conditions and challenges in SC providing by these experts.

Participant 5 stated about the capability of psychologist and chaplain as SC providers as follows: “A person who knows spiritual counseling in mental health field can easily treat those patients with mental health problems in spiritual scope; such person can be a psychologist or a chaplain. If he/she is chaplain, he/she should be expert in mental health and spirituality and if he/she is psychologist, he/she also should be aware of spirituality and mind.”

Others

This group includes other qualified individuals as SC providers. For example, participant 4 pointed to the important role of mystics: “mystics' attitude toward issues is similar to psychologists' attitude believing which human should know the ways that he or she is willing to suggest. Another point is that these individuals have deep opinions about mind and soul giving internal meaning to phenomena.”

General conditions is the second extracted theme indicating the general conditions of spiritual counselors working in this field. This theme includes the following two subcategories [Table 3].

Documents and licenses

This category comprises relevant codes to the fundamental science of SC and all the documents and licenses obtained by individuals interested in SC providing to be active in this field.

Personal characteristics

This includes different personality and behavioral characteristics required for a SC provider. For example, God orientation, being kind, being interested, being dynamic, and up to date can be mentioned in this case. Participant 10 stated about spiritual counselor's belief in meaning and spirituality inside as follows: “suitable individuals for being a spiritual counselor are those who believe in spiritual background of each phenomenon. In other words, they should be esoteric. For instance, pilgrimage (Hajj) does not mean traveling with airplane just to see a holy monument and pray it; in contrary, the person should be aware of traveling toward the God which means forgetting self-centered behavior of human and tending to know God.”

Sciences required is the third extracted theme covering the following three categories [Table 4].

Religious knowledge

Codes in this category indicate types of references, books, techniques, and skills in religious field which should be necessarily learned by spiritual counselor.

Knowledge of psychology

This is a collection of knowledge, skills, and qualifications which should be obtained by spiritual counselor to be successful in this area.

Other knowledge

This category comprises important codes besides two above-mentioned categories in the viewpoint of stakeholders; these codes include social science, biology, and knowledge of physical problem diagnosis.

SC curriculum is another theme about SC learners and teachers and its missions are as follows [Table 5].

Educational materials

This category covers different types of theoretical, practical, survey, and clinical teachings, which should be learned by all learners to be expert in this scope.

Mission

This category answers the following questions: why we should be taught in scope of SC and how this scope helps clients.

Conditions of spiritual counseling instructor

This category belongs to codes which answer the following questions: who can teach SC and what are the requirements for this activity?

Training spiritual counselors is the last theme extracted from data analyses. This is the most significant theme which expresses methods to train spiritual counselors [Table 6].

Educational workshop

This category explains one of the methods for training counselors besides its advantages and disadvantages.

Educational course

It is one of the best methods to teach learners. In this category, conditions required for course holding, course duration, and holding method are explained.

For instance, interviewee 7 stated: “in my opinion, chaplains should be trained for mental health and its principle in order to deliver an ideal spiritual counseling. These discussions should be started in training courses under the supervision of universities and there is no need that chaplain study psychology necessarily. These courses give sufficient knowledge, making them able to diagnose mental disorders.”

Educational major

It is one another method for learners' training. This category explains the necessity for establishment of SC major in Iran and preparing field for it.

In case of training methods for spiritual counselors, participant 12 stated: “One of disadvantages of workshops is giving certificate to all of participants, but training courses are like educational semesters; even it is emphasized in courses which they should have supervision for one period to be identified as qualified counselors by teacher then it is decided after supervision which those individuals can work in this field or not. However, if this major is created, there will be a discipline in it and will have a curriculum. Considering problems in creating a new major, the best way is holding courses to gain experiences and then create it as a new major.”

With respect to the themes, categories, and codes obtained, the following findings can be stated in order to summarize the mentioned results and their better understanding: determining the suitable people to provide SC in mental health is one of the most challenging areas and also codes well illustrate this subject. However, it is possible to say generally which people who are expert in both religion and mental health scopes can provide SC with subject to conditions (although the total codes indicate that it is easier for religious professionals to do this). One of the most important circumstances is the need for their participation in training courses in order to qualify for providing such counseling. It is essential for these professionals to study in the field of religion, psychology, and some other majors.

DISCUSSION

This study addressed the most important challenges to newly emerged topic of SC in the field of mental health in Iran. Since there is little and ambiguous information in this field, the topic was addressed based on the opinions of stakeholders. This approach is a strategic tool used to find behaviors, objectives, interactions, and interests of individuals and organizations in knowledge generation about these elements besides the present and future opportunities and threats.[30]

Results obtained from analyses indicated that what groups and conditions are qualified to provide SC, what kind of knowledge should be known by suitable individuals, who can train spiritual counselor, what they should teach, and what teaching methods should be used.

In order to compare the results of this study with previous ones, we conducted a comprehensive review of various types of internal and foreign databases. However, we could not find a study which directly surveys this subject and its questions. In particular, we did not find a study which explains who should exactly provide SC services. Hence, we cannot compare the overall results of this study with other ones, and this comparison will only be possible in detail.

The first theme expresses that three groups of experts are qualified to provide SC: counselors and psychologists, religious experts, and other groups such as mystics, psychiatrics, and psychic nurses. The common point of these three groups is that they are trained in both mental health and spirituality scopes. For example, Forrester-Jones et al. conducted a study in which the authors explained that patients with psychological problems who have religious beliefs sometimes choose chaplains to solve their spiritual issues.[31] In addition, Memaryan et al. emphasized on cleric expertise in counseling area.[4]

Moreover, numerous studies have pointed to the role of counselors and psychologists in SC providing and necessity of training these individuals in spiritual field, making them empowered to work with different patients.[16] One of the new findings of this study was competency of mystics in providing SC services and training spiritual counselors. In this regard, no study was found in this group of individuals. In addition, the interest and belief of spiritual counselors in spiritual scope are other significant characteristics of spiritual counselors.[32]

Although there were some challenges between beneficiaries in terms of chaplains' competency for SC providing, whole codes introduced this group as more suitable individuals to provide such services because it is more possible in the educational system of Iran to train religious experts in SC courses compared to training experts in mental field within long-term courses related to religion and spirituality.

On the other hand, the majority of SCs provided by experts in mental health integrating religion/spirituality with counseling/psychology[18] called counseling/psychotherapy with spiritual/religious approach.[633] This case was interesting to interviewees so that one of them pointed to the difference between SC provided by counselors and chaplains. However, interviewee 5 stated that metal health experts could be trained through shorter courses for mental health experts and designed by seminaries. In this sense, both groups can be qualified for SC providing.

The third theme addresses sciences which should be known by experts. One category of these sciences in religious and spiritual sciences including using Quran, religious narratives, and applying spiritual technics timely based on the study conducted by Aghajani et al.[9] In addition, results obtained by Der Pan et al. suggested a religious sciences-related framework required for using holy book and pray.[34] Hence, counselor's approach to use religious sciences should be determined.

The two last themes explain training frameworks for spiritual counselors. There are numerous evidences and researches indicating coherent teachings in this field in many countries.[3536] For instance, the UK, Sweden, and Canada have designed spiritual service packages in both physical and mental areas. Even in Canada, spiritual counselors work in specialized scopes such as addiction, grief and crisis counseling, marriage and family, and military counseling. They also receive professional courses. However, there is no educational plan for SC in the field of mental health in Iran,[3738] and since the majority of countries have started career courses in this field considering problems in creating a major, the best method of teaching and training spiritual counselor is conducting professional course. In addition, holding workshops by stakeholders is not effective due to the mentioned barriers. An innovative part of this study was addressing this topic and explaining educational structures for spiritual counselors' activity.

Since spiritual services are rooted in our culture and religion, native guidelines should be created for them as soon as possible[2339] through conducting similar qualitative researches. Furthermore, it is worth considering teaching and training case in this scope to make spiritual service providers concern about solutions to promote these services.[22]

Recommendations and limitations

Lack of a certain proctor in counseling and psychology scope was one of the limitations in this study. Hence, decision-making, policymaking, and implementing instructions for SC–which is one of the counseling branches–is difficult.

One another limitation in this study was addressing several important subjects at the same time. Accordingly, it is recommended to examine these topics separately. Since findings obtained from a qualitative study are based on the opinion of interviewees and more important data analysts and since there are numerous disagreements and challenges to this scope, it is recommended to conduct further studies.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by the Research Council of Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the participants in this research and the members of Spiritual Health Research Center of Iran University of Medical Sciences for their valuable contributions. Data of this article were extracted from dissertation approved and funded by the Research Council of Iran University of Medical Sciences under the ethical code IR.IUMS.REC 1395.9411704008, contract number: 96-02-185-30773.

REFERENCES

- The Problem of Mental Disorder. In: Sociology of Mental Disorder (10th ed). New York: Routledge; 2016. p. :1-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of mental disorders incidence trend in Iran. Daneshvar Med. 2014;21:1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of spiritual counseling on spiritual well-being in Iranian women with cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;30:79-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Content of spiritual counselling for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy in Iran: A Qualitative content analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:1791-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The beneficial role of spiritual counseling in heart failure patients. J Relig Health. 2014;53:1575-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cultural competence in counseling the Muslim patient: Implications for mental health. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2015;29:321-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Educational resources of psychiatry residency about spirituality in Iran: A qualitative study: Iran. J Psychiatry Clin Psychol. 2015;21:175-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of spirituality counseling on anxiety and depression in hemodialysis patients: Evidence Based. Care J. 2014;3:19-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- The contribution of spirituality and spiritual coping to anxiety and depression in women with a recent diagnosis of gynecological cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:755-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Do religious/spiritual coping strategies affect illness adjustment in patients with cancer? A systematic review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:151-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation for pastoral counseling and spiritual care: Strengthening pastoral “felt knowledge” and empathy through the appreciation and use of contemporary films. J Pastoral Care Counsel. 2017;71:41-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Called and committed: The lived experiences of female clergy cancer survivors. Pastoral Psychol. 2017;66:609-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spiritual care for cancer patients in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:4289-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Client-led spiritual interventions: Faith-integrated professionalism in the context of a Christian faith-based organization. Aust Soc Work. 2016;69:360-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spirituality and counselling: Are counsellors prepared to integrate religion and spirituality into therapeutic work with clients? Can J Couns Psychother. 2011;45:1-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spiritual needs of cancer patients: A qualitative study. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:61-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Developing spiritual competencies in counseling: A guide for supervisors. Couns Values. 2016;61:111-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uniting spirituality and sexual counseling: Eastern influences. Fam J. 2006;14:81-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- A contemporary paradigm: Integrating spirituality in advance care planning. J Relig Health. 2018;57:662-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Integration of spirituality in medical education in Iran: A Qualitative exploration of requirements. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:793085.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spirituality in mental health services. Iran J Psychiatry Clin Psychol. 2017;23:6-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spirituality and health care in Iran: Time to reconsider. J Relig Health. 2014;53:1918-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nurses' and caregivers' definition of spirituality from the Christian perspective: A comparative study between Malta and Norway. J Nurs Manag. 2015;23:39-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- An integrative review of the concept of spirituality in the health sciences. West J Nurs Res. 2004;26:405-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Q Health Care. 2007;19:349-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strategies to enhance Rigour in qualitative research. J North Khorasan Univ Med Sci. 2013;5:663-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Including the 'spiritual' within mental health care in the UK, from the experiences of people with mental health problems. J Relig Health. 2018;57:384-407.

- [Google Scholar]

- Critical care nurses' perceptions of and experiences with chaplains: implications for nurses' role in providing spiritual care. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2017;19:41-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Counseling students' perceptions of religious/spiritual counseling training: A qualitative study. J Couns Dev. 2015;93:59-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perspectives of Taiwanese pastoral counselors on the use of scripture and prayer in the counseling process. Psychol Rep. 2015;116:543-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incorporating spirituality into substance abuse counseling: Examining the perspectives of service recipients and providers. J Soc Serv Res. 2013;39:498-510.

- [Google Scholar]

- Religion and spirituality within counselling/clinical psychology training programmes: A systematic review. Br J Guid Couns. 2016;44:257-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Developing a training course for spiritual counselors in health care: Evidence from Iran. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24:145-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Christian counseling the past generation and the state of the field. Concordia J. 2014;40:30-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health care providers' perception of their competence in providing spiritual care for patients. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:57-61.

- [Google Scholar]