Translate this page into:

End-of-life Care: Beliefs, Attitudes, and Experiences of Iranian Physicians

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Context:

Most of the patients suffering from cancer are diagnosed at late stages of cancer, which curative interventions are unable to improve their quality of life.

Aim:

To survey Iranian physicians' attitudes and practices toward end-of-life (EOL) care.

Subjects And Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional survey among physicians participating in a national annually conducted educational seminar.

Results:

The survey results show that 80% of physicians had between 1 and 3 EOL patients. About 72% of patients received medical care in hospitals. The difference in best setting for care of terminally ill patients was statically significant after controlling for the length of practice and physician belief. The results also showed that that the participants believed that that the level of physicians' knowledge in this field was unacceptable.

Conclusion:

Physicians of our study were interested to participating in continuing education programs focused on EOL patients.

Keywords

Attitude

end-of-life care

hospices

knowledge

palliative care

physicians

INTRODUCTION

Prior studies estimate that >15 million people will suffer cancer worldwide by 2020.[1] According to a report by Iran's Ministry of Health, Treatment and Medical Education, over 30,000 Iranians die annually due to cancer, and 70,000 new cases occur every year.[23] Therefore, cancer is the third-most common cause of death in Iran, only following coronary heart disease and road traffic fatalities.[45] There is considerable evidence from the past few decades that shows growth in the number of patients who die from cancer.[1678]

Unfortunately, most cancer patients are diagnosed at late stages of their disease and reach a stage that surgery, chemotherapy, and other curative interventions are unable to improve their life expectancy, and quality of life,[9] so palliative interventions become the only remaining option. End-stage cancer patients often suffer severe distress in physical, psychological, spiritual, social, and financial dimensions.[10] The relief from such a suffering is considered as a basic and universal human right[11] and a basic step in achieving universal health coverage (UHC). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), UHC is defined as access to key preventive, curative, rehabilitative, and palliative care for all at an affordable cost.[12] The main goal of UHC is ensuring that all people acquire the health services they need without suffering financial problems when paying for them.[11131415]

Palliative or hospice care is an interdisciplinary, comprehensive, patient-centered approach in response to these needs. In the hospice model for end-of-life (EOL) care is based on a team approach to control symptoms, manage pain, and provide emotional and spiritual support for terminally ill patients and their families.[16] This service can be delivered at home, which allows patients to spend their end days at home, so the patient's pain is reduced, their satisfaction is increased, and cost-effectiveness goals are achieved.[17] These services include: physicians' services; medical instruments; nursing care; drugs; the services of homemakers and home health helpers; physical, speech, and occupational therapy.[181920212223] The WHO defines palliative care as “an approach to improve the quality of life of for threatening illness situations.”[24] The objective of hospice care is not to cure disease but to alleviate symptoms, and improve quality of life at the EOL.[25] An additional mission of hospice care is to enable the EOL patients to die at home, with the emotional support of their beloved people around them.[26]

Despite the fact that cancer is a leading cause of mortality in Iran, and the rates of late-stage diagnosis of the disease are rapidly growing rate in the country, very little is known about the physicians' beliefs, attitudes, and experiences about of EOL care. This study surveyed Iranian physicians' belief, attitudes, and experiences about EOL care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted this study among all physicians who participated in the largest national annually conducted educational seminar in city of Tabriz, and end of year medical students' educational seminar in September 2012. Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) conducts this seminar on an annual basis, and its participants include clinician-specialists in varied subspecialty groups. The seminar presented an opportunity to obtain the current data on physicians' EOL care training, knowledge and attitudes, demographic and organizational characteristics, and personal experience with terminally ill patients.

The included population consisted of 560 medical students, general physicians, specialist, and subspecialists who attended the seminar. The sample size was determined based on the WHO recommendation on 400 samples.

We collected data through a voluntary, self-administered, and anonymous standardized questionnaire. The “Care of terminally ill patients” questionnaire was originally developed by Csikos et al. in 2010.[27] The validity and reliability of the Persian (Farsi) translation of the instrument were measured after the translation process. We employed a translation – back translation process to translate the original English language instrument. Two English-Persian translators, and two native English and Persian bilingual speaking persons were respectively involved in the translation and back-translation processes. Before the application of the translated questionnaire in the study population, it was piloted among 15 people, and a linguistic edit of the measure was done. We evaluated the content validity of the questionnaire based on the opinions of an expert panel, which consisted of eight health services research specialists. After applying modifications and corrections, the panel approved the content validity. In addition, we assessed the reliability of questionnaire totality using the Cronbach's Alpha coefficient. The calculated Cronbach's Alpha values for all 22 items (0.92) showed reasonable reliability (internal consistency). The final questionnaire contained 22 questions about care of terminally ill patients, 2 demographic questions (age and sex), and 5 questions related to the characteristics of the organization in which the participant worked.

Survey participants received the questionnaires before seminar sessions and internship workshops. Participation was voluntary, and no incentives were offered. Completion of the anonymous questionnaire was taken as consent to participate in the study. The questionnaire included a letter explaining its general purpose and providing assurances of the confidentiality of individual answers.

We manually checked all completed questionnaires for completeness before forwarding the data to an electronic database. We calculated frequencies and percentages to compare results. We also used cross-tabulations and Kendall's tau-beta to test for significance and to compare within-sample bivariate associations between demographic and practice variables with belief and attitude variables. Most of these tests were not statistically significant, with the exception of those reported here. Our data analysis employed SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Ins., Chicago, USA). This article only discusses the quantitative results of our study. Ethical consideration for this study and the study protocol were approved by the Internal Review Board Ethics Committee of TUMS, which was in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration.

RESULTS

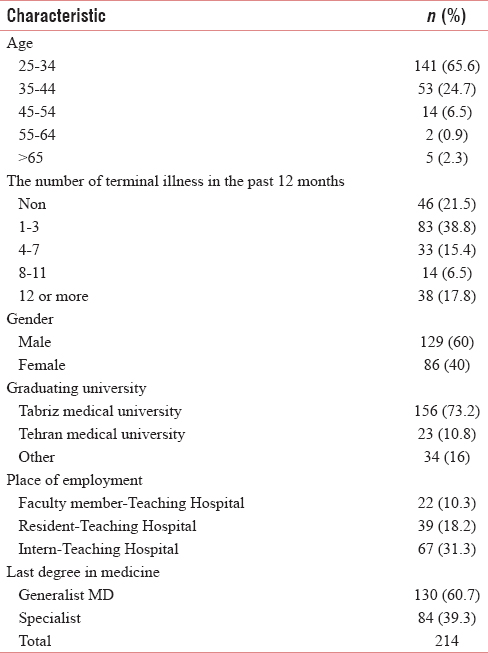

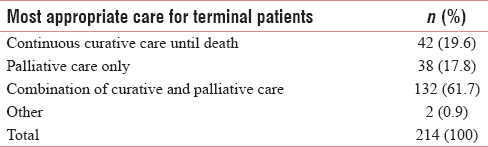

Of the 560 distributed questionnaires we distributed for this study 215 questionnaires were completed (overall response rate of 38.3%). Sociodemographic and organizational characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. More than 80% of physicians have had at last 1–3 EOL patients. It is considered that 72% of the mentioned patients received medical care in hospitals, 23% at home and only 4.7% in other settings. After controlling for physician gender groups and specialty, we found no statistically significant differences in the number of patients the physicians visited per day, however, differences in number of terminal illness patients they had visited were statically meaningful (P < 0.0001). Physicians' beliefs about the most appropriate type of care for EOL patients illustrated in Table 2.

Physicians' opinion on the current quality of care for EOL patients in Iran were: 1.9% indicated the best, 15.8% sufficient with deficiencies, 59.5% insufficient, and 22.8% there is not any care. Furthermore, their response to the question: “In your opinion, the best setting for care of terminally ill patients is usually” approximately were: 20% hospital, 62% the patient's home, 18% a nursing home, that is in contrast with their practice which indicates that over 72.4% of EOL patients were cared for in hospitals. Furthermore, the differences among general practitioners and specialists about the best setting for care of terminally ill patients were statically significant (P < 0.0001). On the other hand, differences in age, gender, working place, and universities of physicians were not statically significant.

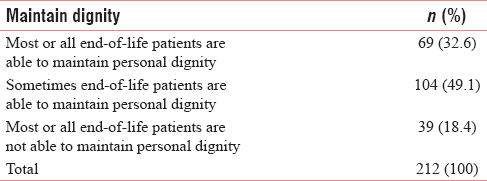

Physicians' beliefs about the ability of EOL patients to maintain dignity until death is summarized in Table 3. Further investigation about the differences observed in Table 3 did not show any significant relationship between specialty, age, gender, workplace, and universities of physicians.

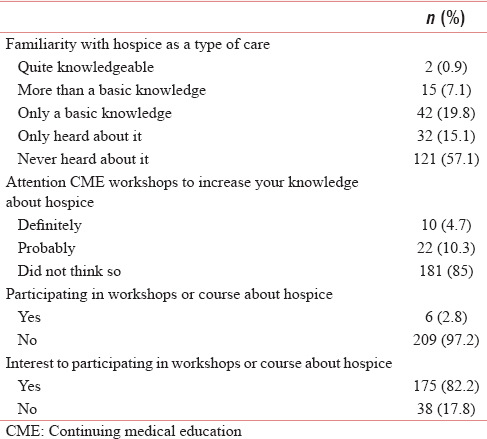

Nearly 1% of physicians stated that they were quite knowledgeable about hospice care and 57.1% did not possess any familiarity with this type of care. The majority (97.2%) of the physicians indicated that they had not participated in any educational course about hospice care and 82.2% of them were interested in participating in an educational course on hospice care. Table 4 shows familiarity of physicians with hospice care and their interest in participating in the educational course.

Investigation on significant relationship between physicians' knowledge about hospice and demographic characteristics were meaningful only in age groups (P = 0.025).

DISCUSSION

There are numbers of important implications of this study. First, the study demonstrates that the familiarity of Iranian physicians' with EOL care is low and in contrast with the frequent contact with mentioned patients. Second, there is not any kind of structured or organized system to deliver services for EOL patients. Third, in Iran, there is a noticeable absence of EOL education, in both medical school curriculums, and in continuous medical education programs.

The participation rate in this study was 38.3%, which was lower than that of similar international studies in Hungary (54%), United States (48%), and Pakistan (63.6%).[2728] These differences could be attributed to methods of sampling and low level of Iranian physicians' knowledge about EOL care.

Most of the Iranian physicians (72%) in the current study claim that they did not have any knowledge about hospice care, which is more than Pakistani physicians (57.1%) who stated that they had heard about a hospice.[28] In contrast to the most of the U.S. physicians who were quite knowledgeable, most of the Hungarian physicians had only a basic knowledge.[27] However, there is a high level of interest shared among physicians in the U.S., Hungary, Iran (82%), and Pakistan to participate in continuing medical education to learn more about hospice care. These findings are consistent with previous studies that indicate physicians' common interest in continuing medical education for EOL care.[102728293031]

In this study, 72% of EOL patients received medical care in the hospital and 23% at home, while only 27% of Iranian physicians mentioned that the preferred place of providing terminal care is the hospital. We think that the reason for this conflict is related to lack of any EOL care in Iranian health system, both in the hospital or home. This is confirmed by 82% of physicians which indicated that the level of present EOL care in Iran is insufficient, and 22% believed that there is not any structured service for EOL patients. Other studies focus on physicians' awareness of patients' preferred place for dying.[3233] Our findings are in accordance with other study results and reports that categorize Iran in the second group on palliative care development in the world.[34] Iranian physicians believed that combination of curative and palliative care is the most appropriate approach for terminally ill patients (61.7%) which matches with U.S. physicians and is in contrasts with most of the Hungarian physicians that supported a palliative care only approach for terminally ill patients.[27] This difference between Iran and Hungary may be attributed to the current practice of aggressive curative treatment until the last days of life.

We found Iranian physicians' beliefs about the ability of EOL patients to maintain personal dignity were different from those of other countries.[2733] This difference is quantified by the question “Most or all EOL patients are not able to maintain personal dignity” which was 18% in the present study but 9% and 5%, in Hungary and the U.S. These differences could be attributed to the difference of social contexts and family structures in these three countries.

Most of the Iranian physicians in the current study claim that they would like to participate in educational course about hospice care if it was offered in college curriculums or in continuous medical education programs. These results are similar to most of the U.S. and Hungarian physicians' opinion[27] but are in contrast with previous studies on Iranian nurses.[11] Intense interest of the Iranian physicians to participate in continuous medical education for EOL care is another finding of this study.

CONCLUSION

Our findings reveal unacceptable levels of knowledge and attitudes of physicians about delivering services for EOL patients. The low response rate for questionnaires in the present study was the main limitation of the study, so it might not truly represent all physicians of Iran. However, based on the present study, physicians were interested in participating in continuing education programs about patients with terminal illnesses. In response to these realities, designing-specific care for EOL patients is inevitable and should be starting as soon as possible. Furthermore, the education of physicians about EOL care should be included in the formal curriculums of medical schools and continuous medical education programs.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- Dying with cancer, living well with advanced cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1414-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spiritual care at the end of life in the Islamic context, a systematic review. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2012;1:63-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of cancer cases using capture-recapture method in Northwest Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:3237-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles 2011. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization; 2011.

- The need for palliative care services in Iran; an introductory commentary. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2012;1:1-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors of colorectal cancer among patients admitted to Imam Reza university hospital, a referral center in North-West of Iran. J Clin Res Gov. 2014;3:158-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhancing patient-reported outcome measurement in research and practice of palliative and end-of-life care. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1573-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caring for Dying and Meeting Death the Views of Iranian and Swedish Nurses and Student Nurses. Luleå Tekniska Universitet 2009

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care as an international human right. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:494-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Universal health coverage: A quest for all countries but under threat in some. Value Health. 2013;16:S39-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trends in the aggressiveness of end-of-life cancer care in the universal health care system of Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1587-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- The public health strategy for palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:486-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physicians' preferences for hospice if they were terminally ill and the timing of hospice discussions with their patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:466-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Access to hospice care: Expanding boundaries, overcoming barriers. Palliative Care: Transforming the Care of Serious Illness. 2010;Vol. 13:159-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advance care planning and hospice enrollment: Who really makes the decision to enroll? J Palliat Med. 2010;13:519-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tell us™: A Web-based tool for improving communication among patients, families, and providers in hospice and palliative care through systematic data specification, collection, and use. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42:526-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mind-body treatments for the pain-fatigue-sleep disturbance symptom cluster in persons with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:126-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Age related secretary pattern of growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-I and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 in postmenopausal women. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:598-602.

- [Google Scholar]

- Illness trajectories and palliative care: implications for holistic service provision for all in the last year of life: Scott A. Murray and Peter McLoughlin. International Perspectives on Public Health and Palliative Care 2013:43-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physician knowledge, attitude, and experience with advance care planning, palliative care, and hospice: Results of a primary care survey. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30:419-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physicians' beliefs and attitudes about end-of-life care: A comparison of selected regions in hungary and the United States. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:76-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Awareness of palliative medicine among Pakistani doctors: A survey. J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54:195-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer in Sudan: Palliative care is the most rapid way to less suffering. Sudan Med J. 2012;48:112-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- End-of-life care in urban areas of China: A survey of 60 oncology clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:125-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caring at the end of life: Iranian nurses' view and experiences. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2012;2:9.

- [Google Scholar]

- General practitioner awareness of preferred place of death and correlates of dying in a preferred place: A nationwide mortality follow-back study in the Netherlands. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:568-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- ISDOC Study Group. End-of-life care in Italian hospitals: Quality of and satisfaction with care from the caregivers' point of view – results from the Italian survey of the dying of cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:1003-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- The international observatory on end of life care: A global view of palliative care development. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:542-6.

- [Google Scholar]