Translate this page into:

Impact of Educational Training in Improving Skills, Practice, Attitude, and Knowledge of Healthcare Workers in Pediatric Palliative Care: Children's Palliative Care Project in the Indian State of Maharashtra

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

The “Children's Palliative Care Project” was initiated in October 2010 in the Indian state of Maharashtra with a view to improve the quality of life of children with life-limiting conditions. This study evaluates its education and training component through a questionnaire.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was carried out pre-/post-training among 258 doctors, nurses, social workers, and counselors at three sites in Maharashtra in March 2015. Descriptive statistics were used for data analysis.

Results:

Sixty-two participants responded. Posttraining, doctors and the nurses had a better level of knowledge, skill set, and attitude; whereas social workers and counselors fared better with prevailing care practices. Participants advocated using morphine only when other analgesics had failed and suggested ways for better service delivery of care.

Conclusion:

The study gives a rough idea of the prevailing practice of pediatric palliative care among the health-care workers (who participated in the survey) and suggests practical ways to improve it.

Keywords

Indian association of palliative care

palliative care

pediatrics

survey

INTRODUCTION

New advances in medicine have improved survival among children with most of the life-limiting illnesses. In the last 40 years, the overall survival rate for children's cancer has increased from 10% to nearly 90% today, but for many childhood cancers, the global survival rate is much less. There is little data from India, but according to the Million Death Study (a cohort of >27,000 pediatric deaths in India on the basis of enhanced verbal autopsies), an overall age-standardized mortality rate due to cancer deaths in childhood (1 month to 14 years of age) is 39 (95% confidence interval: 33–44) per million population per year.[1] However, in the society, the strongly held belief that “Children are not supposed to die” creates societal barriers to facing this reality.[2] When the hope of cure and prolonged survival dwindles, families and caregivers face tremendous stress. Care at this stage requires a holistic approach to the patients' and families' physical, emotional, and spiritual needs.[3] The World Health Organization (WHO) defines palliative care for children as the active total care of the child's body, mind, and spirit, and also involves giving support to the family. It begins when the illness is diagnosed and continues regardless of whether or not a child receives treatment directed at the disease. Health-care providers must evaluate and alleviate a child's physical, psychological, and social distress. Effective palliative care requires a broad multidisciplinary approach that includes the family and makes use of available community resources; it can be successfully implemented even if resources are limited. It can be provided in tertiary care facilities, in community health centers and even in children's homes.[2] It is recommended that palliative care starts ideally at the time of diagnosis and extends all through the disease trajectory into bereavement support. This multidisciplinary approach requires proper networking with local medical facilities, home care, or access to local hospice. Health conditions benefitting from palliative care are not only limited to advanced cancer but can also be extended to conditions including cystic fibrosis, Batten's disease, and cerebral palsy as highlighted in ACT/RCPCH categories in pediatric palliative care.[4]

In India, it is estimated that 1 out of 10 children with cancer, 1 out of 2 children with cerebral palsy, 1 out of 7 with human immunodeficiency virus, 1 out of 10 with thalassemia, and 1 out of 5 with neurodegenerative disorders will need palliative care at any point of time.[5] Yet, specialist pediatric palliative care is in its beginning in India. According to the Global Atlas of Palliative Care, India, has attained level two integration, that is, sporadic distributions of services for the provision of pediatric palliative care.[6] In India, most children with advancing diseases are cared for by local general practitioners who are graduates in medicine/surgery and have not received specialized clinical training in pediatrics. Yet, the parents would like to return home and get the best possible medical assistance as there is the rest of the family to be cared for along with the sick child.[7] Trying to identify innovative options to care for this stretched family takes all the skills available to be put to use. On this background, the “Children's Palliative Care (CPC) Project” of the Indian Association of Palliative Care was initiated in October 2010 in the state of Maharashtra with a view to improving the quality of life of children with life-limiting conditions. The project aimed to increase government commitment to provide CPC in the state. The objectives were to educate and train health-care providers to improve their capability, capacity, productivity, and performance in the delivery of palliative care for children.

CPC project was mentored and guided through organizations including the Hospice UK, International CPC Network and Tata Memorial Centre (Mumbai) with funding through the Department for International Development, UK. It worked through the development of three model sites in Maharashtra based on the model of CPC at Tata Memorial Hospital. The trainers were mostly specialists in pediatrics, palliative medicine, nurse educators, and social workers from academic institutions. The experience and the data gained through these centers were shared with the policymakers to advocate the need for Pediatric Palliative Care in India. This 5-year project was concluded in March 2015.

It has been learned through previous research, that educational meetings alone or combined with other interventions, can improve professional practice and health-care outcomes for the patients.[8] We applied the same principle to educate and train health-care providers to fulfill the objectives.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Various activities were carried out to educate and sensitize different stakeholders in the CPC project – health-care providers, policymakers, caregivers, general population, media, and the beneficiaries. The activities included the development of different training modules, sensitization of stakeholders, identification of nodal personnel, centers, contents, course material, budget plan, coordination with institutes such as Indian Academy of Pediatrics and private hospitals. Training manuals were prepared with modules on pain management, access to analgesics, symptom assessment, and management, communication with children and the families, dealing with adolescents, play and diversion therapies, spiritual counseling, emergencies, ethics, policies, and resources. These modules were standardized and uniformly conducted biannually in the project areas. The project advocated for the inclusion of “Palliative Care” modules in undergraduate and postgraduate medical curricula from 2013 to 2014. It utilized various teaching techniques such as training of trainers, sensitization program, and hands-on clinical experience for physicians tailored to their knowledge and skills in a unique client-centered approach.

The project was concluded in March 2015 and a cross-sectional study was initiated to assess the effectiveness of the program. The study population was selected by sampling from the three project sites as these have academic affiliations and have the infrastructure to train a large number of trainees. There were two urban centers: Pediatric Center of Excellence (PCoE), Sion for HIV care, and MGM Women and Children's Hospital and 1 rural center: Jawhar Cottage Rural Hospital, rural community-based palliative care center. These participants were contacted telephonically and were invited to take part in the training program.

Development of survey questionnaire and scoring

An advisory group was formed to develop a questionnaire to monitor the effectiveness of the educational program. This advisory group comprised palliative care specialists, pediatricians, and lay members of public and health workers with extensive experience in community health programs in the target centers. Group discussion, interaction, and individual reflection were encouraged. The questionnaire was administered to the participants in person by the project coordinators at the beginning and again at the end of educational sessions, but the format was kept simple with clear instructions and easy to complete response format to be completed over the telephone if deemed necessary. The questionnaire was administered in the English language as all the participants were proficient in English. Since the questionnaire aimed to measure the effectiveness of the educational program, ordinal response categories with interpretable scale scores were considered to be appropriate.[9] This not only aimed to simplify responses but also facilitate straightforward analysis. The order of questions was kept flowing in a logical sequence to make the questionnaire easy to work through. Furthermore, all statements were kept succinct and the wording as simple as possible, with additional information beneath each statement to ensure that the focus of the statement was clear.[10] The questionnaire comprised 25 questions. An opportunity was provided at the end of the questionnaire for participants to provide spontaneous feedback. All respondents were given the option of being anonymous, with the aim of encouraging participation and truthful feedback. An independent expert panel was approached to provide an “expert” review of the draft questionnaire and support its face validity before finalization in English [Appendix 1].[11] The final questionnaire consists of questions regarding knowledge on basic concepts of palliative and end-of-life care, management of pain, and other symptoms in palliative care. Out of a total of 25 questions, 23 can be arranged in four groups such as skills, practice, attitude, and knowledge [Appendix 1.1]. The rest explores contact with any other palliative care training and the major barriers to the provision of palliative care in their setups. All the responses were coded into numbers employing suitable numerical scale so as to facilitate processing [Appendix 1.2].

The participation to study was on a voluntary basis. All participants were given a briefing about objectives of the study and assured confidentiality in the collection of personal data. For the purpose of filling the forms, interviews were conducted with the participants by the trial coordinator in a language best understood by them over the telephone after taking informed consent from them. The raw scores were transformed into weighting scores based on previous research.[12] Data were entered in MS Excel and analyzed. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

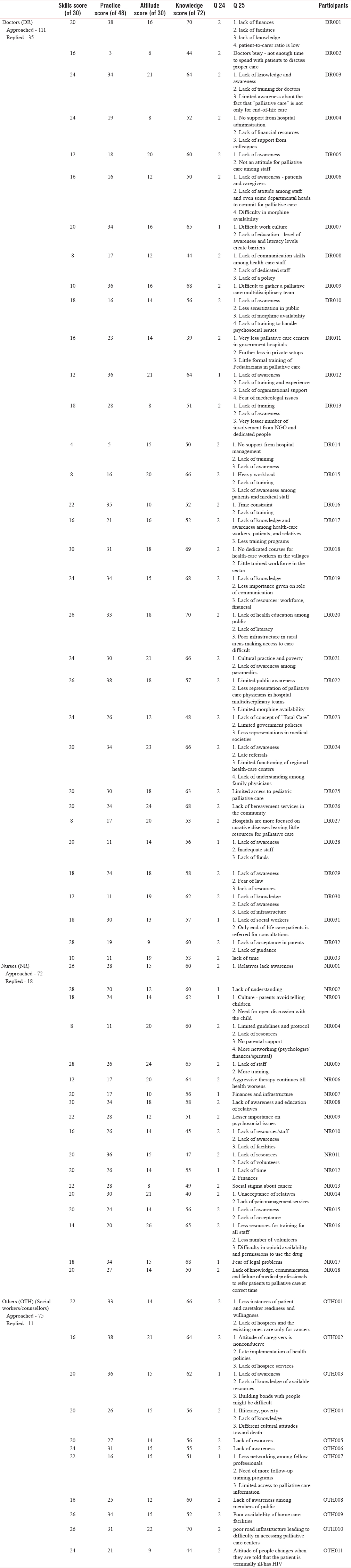

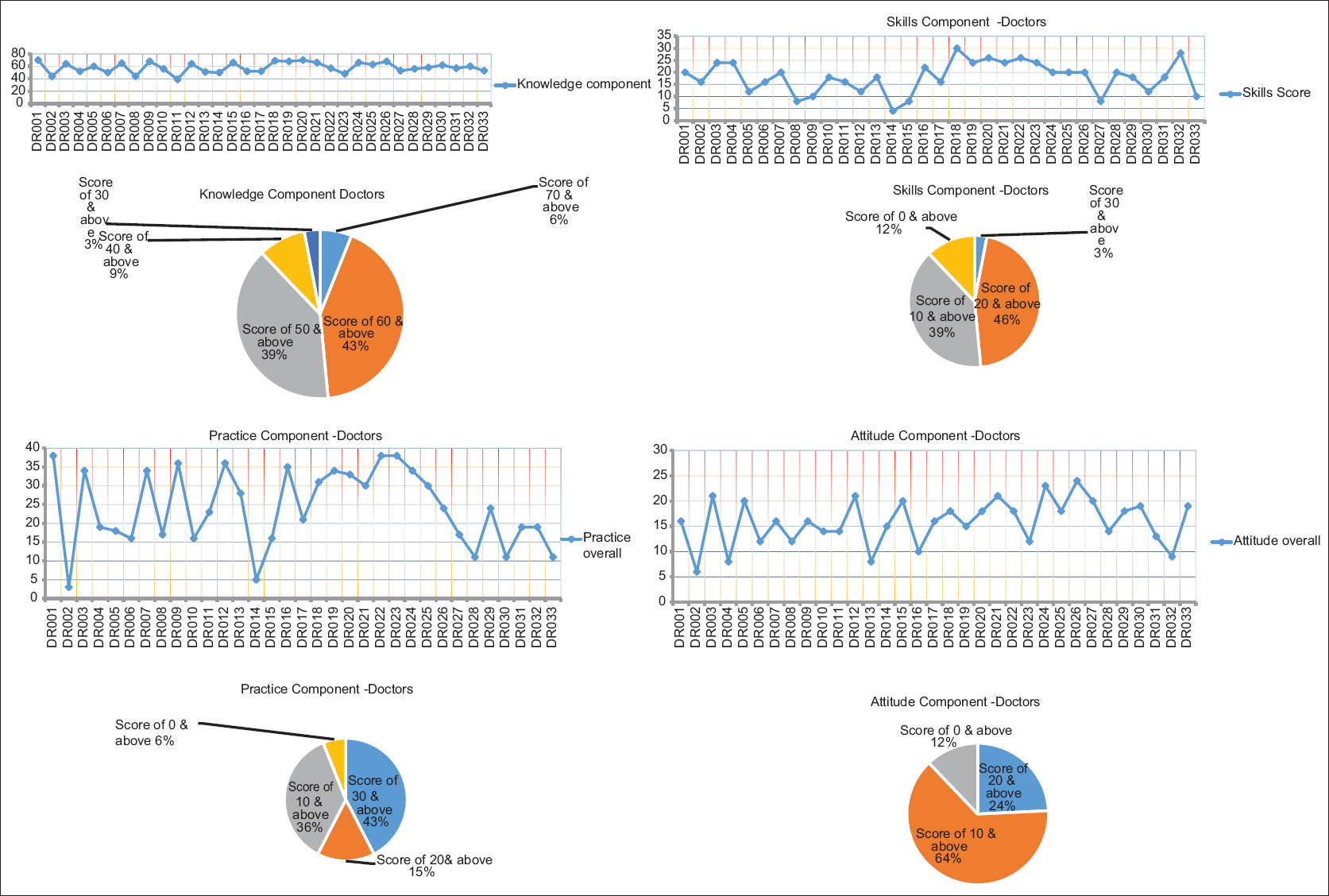

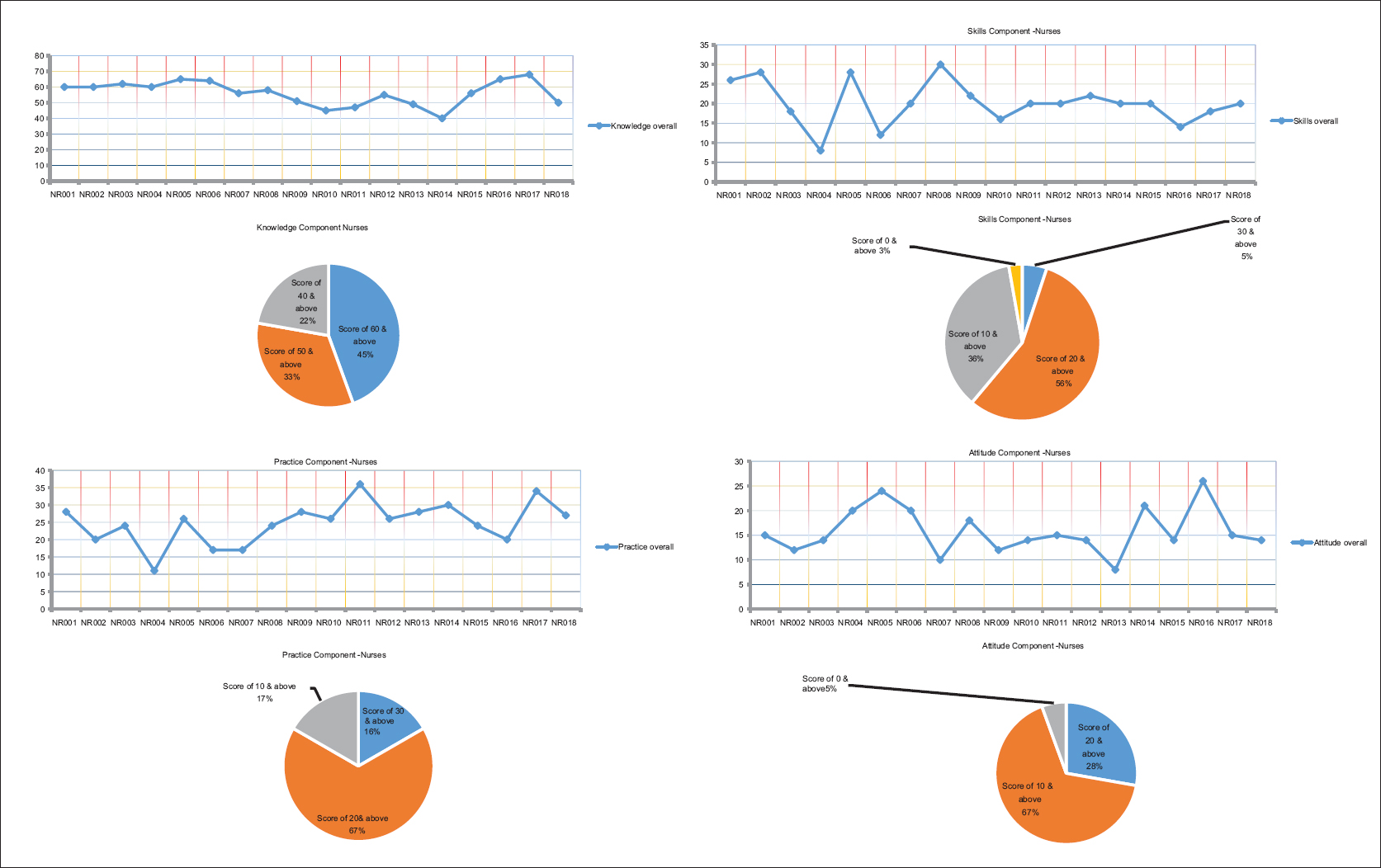

Responses were gathered from a total of 62 (24.03%) participants (out of 258) approached for the study – 17 men and 45 women. 33 were doctors, 18 were nurses, whereas 11 were social workers and counselors (others). 43% of the doctors and 45% of the nurses had shown a good level (good [70%–100%], medium [31%–69%], poor [0%–30%][13]) of knowledge with a score of 70 and above, while 45% of others showed a medium level of knowledge with a score of 50 and above. Despite the good level of knowledge among the health-care workers, a major disparity was noted in the skills domain. It was seen that 46% of doctors and 56% of nurses felt that they have a poor skill set (scores of 20 and above), while it was worse with others with 82% of them falling in the same category. In the domain of prevailing palliative care practices, 43% of the doctors and 55% of the others had a mere score of 30 and above, which was worse in nurses with 67% scoring 20 and above. In the section of attitude toward palliative care, 64% of doctors and 67% of nurses scored a dismal 10 and above with 73% of others to follow the same way. A total of 4 (6.4%) participants opined about using morphine at the first sign of pain, 46 (74.2%) participants opined about using morphine only when other analgesics fail, whereas 12 (19.4%) did not advocate the use of morphine at all [Table 1].

The individual responses were analyzed in further detail. It revealed that 91% of the doctors expressed that public awareness, government policies, increase in palliative care centers, opioid availability, and more training are necessary to make palliative care accessible for all. 73% of them believed palliative care should be started at the time of diagnosis, 18% felt that it should be started during the treatment phase, and 9% felt that it should be started when treatment fails. 73% felt that the training provided to them under CPC project had empowered them with the knowledge to provide palliative care to children. 88% felt that their skills about pain and symptom management have improved after the training. 24% doctors said that their knowledge of pain management has improved extensively while 73% reported a moderate improvement. For symptom management, 49% felt that their knowledge had improved extensively, while it was reported to be moderately improved by 48%. 70% expressed that CPC can improve quality of patient care by networking with all the facilities such as hospices, home care, video conferencing, networking with local physicians, and nongovernmental organizations. In this regard, 55% were aware of the list of supportive services in their area. All of them agreed that communication is the most important aspect of palliative care. As far as prevailing palliative care practices are concerned, 37% shared that all the aspects such as symptoms control, psychological support, spiritual care, support, and knowledge impartation to caretaker are being provided in their setups. 18% shared that their setups have some of the aspects mentioned above, but 33% expressed that palliative care is not provided in their setups. The reasons include administrative barriers, less priority, and staff constraints [Table 1].

83% of the nurses felt that with the training provided to them, they have now the knowledge to provide palliative care to children. Furthermore, 88% felt that their skills about pain and symptom management have improved after the training. In practice, 44% shared that aspects such as symptoms control, psychological support, spiritual care, support, and knowledge impartation to caretaker are provided in their setups, while 33% are not practicing palliative care. All of the others felt that with the training provided to them, they were better equipped to provide palliative care to children. 73% of others believed that a multidisciplinary approach will improve patients' access to palliative care. They felt that better government policies, easy opioid availability, further training and more public awareness are essential for the growth of palliative care. 91% knew of the psychosocial issues involving the child and family and were confident of handling them. 91% were aware of the supportive services in their area and felt that they were adequate. 64% believed that there has been a moderate increase in their knowledge post the training. All of them felt equipped to handle the pressures of pediatric palliative care and 64% were completely confident about their ability post training. Interestingly, 64% of others felt that their pain and other symptom management has moderately increased because of the training received and 82% of them scored themselves high on the skills component of the questionnaire. On the question of different areas of scope for palliative care in their practice, the others were equally divided among the many options – 73% of others interviewed mentioned about some aspects of existing palliative care in their current practice. Only 27% of others said that end-of-life care issues or the imminent death of the child were extensively discussed with the child, whereas 82% discussed these issues extensively with the parents/guardians of the child. An astounding 50% of others stated that education about bereavement in children is not provided to the staff of their organization. 100% of them wanted to work in providing palliative care for children [Table 1 and Figures 1–3].

- Knowledge component - Doctors

- Knowledge component -Nurses

- Knowledge component - Counselors

DISCUSSION

The WHO claims that palliative care has to be a part of the curriculum of basic health professional education.[14] At the start of the CPC project, many gaps were recognized, like myths of palliative care being “End-of-Life Care” or only for cancer. Palliative Care was not included in any of the professional curricula of mainstream medicine courses. Prevailing practice lacked a multidisciplinary and holistic approach and more focus was laid on curative intent by the primary consultant. Many times, planning of care proved to be a challenging task for the health-care providers due to the varied disease trajectories. Serious challenges to the delivery of palliative care were recognized and included lack of resources, poverty, illiteracy, lack of awareness, superstitious beliefs, and lack of knowledge about the diseases. There were strict regulations and myths regarding opioids which served as barriers to providing pain relief.

The project performed well in improving the numerical adequacy of CPC trained health workers, as slightly over 80% (121) of the target 150 health workers had been trained by December 2014 and more than 1000 sensitized against a target of 300. Going beyond the numbers reached, there is also evidence of improvements in health worker knowledge on CPC as a result of the capacity building initiatives. Findings from a follow-up assessment of the skills, attitudes, practices, and knowledge (SPAK) of trained health workers revealed moderate-to-high knowledge levels among trained doctors and nurses. The mean composite knowledge scores were 81%, 78%, and 80% for doctors, nurses, and others, respectively. Although in the absence of a baseline and counterfactual, the findings cannot be conclusively used to suggest training effectiveness, they are indicative of desirable knowledge levels.

Trained health workers' perceptions and judgment of the training confirmed the gain in knowledge as well as the appropriateness of the methods used in the knowledge transfer. Those who received training felt the training was imparted by professionals who understood the subject well and used appropriate methods and techniques to deliver the content. The participants strongly felt that they acquired a significant amount of knowledge, which they illustratively indicated as ranging from three- to six-fold from what they possessed before the training. Using the battery technique, respondents collectively valued their knowledge before training at levels ranging from 10% to 20% while that after training ranged from 60% to 80%.

Advocacies under the CPC project also led to palliative care become a part of the curriculum for MD Pediatrics in Medical schools under the Maharashtra University of Health Sciences, Nashik.[15]

Similarly, a study by Sadhu et al.[16] and another by Giri and Phalke.[17] mentioned clear gaps in palliative care knowledge among undergraduate health-care students. A study by Karkada et al.[18] showed that 79.5% of nursing students had poor knowledge on palliative care. Another study by Prem et al.[19] found that overall level of knowledge about palliative care was poor amongst nurses. One more study by Weber et al.[20] in Germany also found insufficient knowledge about palliative care among final-year medical students. A study by Fadare et al.[21] clearly showed the gaps in the knowledge of health-care workers in the area of palliative care. Another interventional study by Valsangkar et al.[22] among interns revealed that there is a significant increase in the level of knowledge regarding palliative care after training workshop. In that respect, our study corroborates these findings apart from justifying our hypothesis.

Our study has several limitations worth mentioning. Previous research has shown that educational meetings alone or combined with other interventions as used in this study has little effect on changing complex behaviors of health-care practitioners.[8] Hence, we used strategies to increase its effectiveness by ensuring better attendance through mentorship, networking, using mixed interactive and didactic formats, and by focusing on outcomes that are likely to be perceived as serious. We have used a small sample of participants in this study which limits its representativeness to the whole population, but this can be justified as there are few pediatricians practicing palliative care in India. Again, conversion of raw scores into weighted scores might have caused some methodological flaws, but such an approach has been well documented in the literature.[12] In this study, the questionnaire was neither validated nor translated before administration. We tried to minimize this effect by involving experts in the formulation of the questionnaire. We also engaged a trial coordinator who could administer the instrument over the telephone in a language that the participants best understand. No institutional review board approval was taken for this study. Furthermore, the responses reflect self-practice of a handful of health-care personnel which might be very different from the situation on the ground. However, the results were discussed with senior experts in the field to reduce sampling bias.

This one-shot experimental study indicates fair gains toward furthering the cause of CPC by providing suitable training modules to the stakeholders. A more comprehensive research project employing a properly defined “design of experiments” framework needs to be carried out to standardize the training tailored for the participants. It would also be worthwhile to keep track of those participants to understand the effectiveness of knowledge and skills acquired through the training is being implemented and advanced by them. Such a longitudinal study would help designing better strategies for improving CPC practices.

CONCLUSION

The majority felt that the training provided to them under CPC project has empowered them with the knowledge to provide palliative care to children. Participants advocated using morphine only when other analgesics fail and had many constructive opinions for better availability of palliative care to needy children and their families.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We express our gratitude to the Indian Association of Palliative Care and Department for International Development (UK) for funding the project. We would also like to acknowledge the contribution of experts Dr. N. J. Rathod, former Jt. Dir. Of Health Services (Medical), Maharashtra; Ms. Melba Cardoz, Medical Social Worker, Tata Memorial Hospital; and Dr. Vivek Patkar, volunteer at JASCAP whose help has been immense in formulating the questionnaire and working throughout the project. We heartily acknowledge the cooperation and support of Ms. Vandana Punjabi (project coordinator) for her devoted work and all the concerned staff from Pediatric Center of Excellence (PCoE) Sion, MGM Women and Children's Hospital, and Jawhar Cottage Rural Hospital. Finally, we would like to extend our sincere gratitude to all the participants in the study without whom the project would never have been completed.

REFERENCES

- Childhood cancer mortality in India: Direct estimates from a nationally representative survey of childhood deaths. J Glob Oncol. 2016;2:403-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- The death of children: Our failures and possibilities. Paediatr Child Health. 2003;8:337.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effective Factors in Providing Holistic Care: A Qualitative Study. Indian Journal of Palliative Care. 2015;21:214-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Disease trajectories and ACT/RCPCH categories in paediatric palliative care. Palliat Med. 2010;24:796-806.

- [Google Scholar]

- Paediatric palliative care: Theory to practice. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17:S52-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance. (2018) WHO Global Atlas on Palliative Care At the End of Life. [online]. Available from: http://www.thewhpca.org/resources/global-atlas-on-end-of-life-care

- [Google Scholar]

- Specialist pediatric palliative care referral practices in pediatric oncology: A large 5-year retrospective audit. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:266-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Continuing education meetings Bjørndal A, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, O'Brien MA, Wolf F, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009:CD003030.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interpretation of response categories in patient-reported rating scales: a controlled study among people with Parkinson's disease. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2010;8:61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim, A (1992) Questionnaire Design, Interviewing and Attitude Measurement, London, Pinter Pp 303. £1499 paperback, £3950 hardback ISBN 185567 0445 (pb), 185567 0437 (hb) J. Community. Appl. Soc. Psychol.. 1994;4:371-2. doi:10.1002/casp.2450040506

- [Google Scholar]

- Transforming children's palliative care-from ideas to action: Highlights from the first ICPCN conference on children's palliative care. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:415.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictive validity of demographically adjusted normative standards for the HIV dementia scale. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2008;30:83-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimal number of response categories in rating scales: Reliability, validity, discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2000;104:1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Introduction of palliative care into undergraduate medical and nursing education in India: A critical evaluation. 2004. Indian J Palliat Care [serial online]. 10:55-60. Available from: http://www.jpalliativecare.com/text.asp?2004/10/2/55/13886

- [Google Scholar]

- Indian Association of Palliative Care | MUHS Includes Palliative Care in Paediatric Postgraduate Curriculum. Available from: http://palliativecare.in/muhs-includes-palliative-care-in-paediatric-postgraduate-curriculum

- Palliative care awareness among indian undergraduate health care students: A needs-assessment study to determine incorporation of palliative care education in undergraduate medical, nursing and allied health education. Indian J Palliat Care. 2010;16:154-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge regarding palliative care amongst medical and dental postgraduate students of medical university in Western Maharashtra, India. Chrismed J Heal Res. 2014;1:250.

- [Google Scholar]

- Awareness of palliative care among diploma nursing students. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17:20-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of nurses' knowledge about palliative care: A quantitative cross-sectional survey. Indian J Palliat Care. 2012;18:122-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and attitude of final – Year medical students in germany towards palliative care – An interinstitutional questionnaire-based study. BMC Palliat Care. 2011;10:19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare workers knowledge and attitude toward palliative care in an emerging tertiary centre in south-west nigeria. Indian J Palliat Care. 2014;20:1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of knowledge among interns in a medical college regarding palliative care in people living with HIV/AIDS and the impact of a structured intervention. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17:6-10.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix 1: Questionnaire used

Appendix 1.1: Groups of questions

Appendix 1.2: Conversion of raw scores into weighing scores Q1-Q23