Translate this page into:

Providing Palliative Care in Rural Nepal: Perceptions of Mid-Level Health Workers

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

Nepal is beginning to develop palliative care services across the country. Most people live in rural areas, where the Mid-Level Health Workers (MHWs) are the major service providers. Their views on providing palliative care are most important in determining how the service is organized and developed.

Aim:

This study aims to ascertain the perceptions of MHWs about palliative care in their local community, to inform service development.

Methods:

A qualitative descriptive design, using focus group discussions, was used to collect data from a rural district of Makwanpur, 1 of the 75 districts of Nepal. Twenty-eight MHWs participated in four focus group discussions. The data were analyzed using content analysis.

Result:

Four themes emerged from the discussion: (i) suffering of patients and families inflicted by life-threatening illness, (ii) helplessness and frustration felt when caring for such patients, (iii) sociocultural issues at the end of life, and (iv) improving care for patients with palliative care needs.

Conclusion:

MHWs practicing in rural areas reported the suffering of patients inflicted with life-limiting illness and their family due to poverty, poor access, lack of resources, social discrimination, and lack of knowledge and skills of the health workers. While there are clear frustrations with the limited resources, there is a willingness to learn among the health workers and provide care in the community.

Keywords

Mid-level health worker

palliative care

rural

INTRODUCTION

Nepal is a developing country beginning to provide palliative care services, but with most initiatives limited to the capital city, Kathmandu. There are many who live in rural area who could benefit from the service but lack access.[1] Developing accessible and affordable palliative care programs for rural Nepal are a compelling medical, social, and moral obligation.

Most health services in rural Nepal is delivered by >8,000 MHWs known as Health Assistant or Auxiliary Health Workers in Government services across the country.[2] Thus, to develop palliative care services in rural Nepal, the MHWs play a major role.

No research has been conducted to find the perceptions of MHWs in providing palliative care in rural community in Nepal. Thus, the aim of this study is to ascertain the perceptions of MHWs in relation to palliative care and the care of dying in their local community to help inform the development of palliative care services.

METHODS

A qualitative descriptive design using focus group discussion was used to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the perceptions of MHWs working in rural areas of Nepal about the care of the patients with life-threatening illness. This study was conducted in the district of Makwanpur which was selected as this represented a typical district with difficult topography in a hilly terrain but within a reasonable distance of about 6 h drive from Kathmandu.

Sample

MHWs in Makwanpur were recruited using a purposive approach. From the list obtained from District Health Office of Makwanpur, letters were sent to 35 of 71 MHWs from which 28 participants took part in four discussion group. The rest were excluded from invitation because they had not completed a year in a rural area or worked in a health facility far from the proposed centered to hold discussions. There were 12 females and 16 male participants. The work experience varied from 1 year to 38 years (average 13.5 years). Nine of them had worked in districts other than Makwanpur in the past. The total number of districts the participants had worked altogether was 20, out of the 75 districts in Nepal.

Data collection and analysis

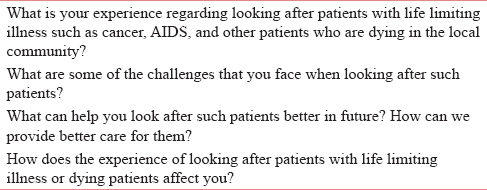

A semi-structured questionnaire to guide the discussion was developed [Table 1]. The discussion was conducted by the first and second authors in four different health facilities in Makwanpur. The guiding questions were put forward to the group, and free flow of discussion was allowed, without interference from the facilitators except using some probing questions such as “can you explain further?” or “is there anything anyone would like to add?” or “can you give an example?.” Each discussion lasted approximately 60–90 min. As no new information was forthcoming, it was considered that data saturation has been reached after four group discussions.

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim into Nepalese by a neutral person and checked by the first author for any omissions or mistakes which were corrected. Data analysis using thematic content analysis [3] included reading and re-reading the text several times followed by open coding, forming categories, and compilation of emerging themes. The process was performed manually. The transcribed text was read by the second and third authors. The discussion was held to agree the result collated by first author and themes were then agreed on by all authors.

Member checking was performed by discussing the results of the study with six participants who had taken part in the group discussion.

Ethical consideration

There were no serious risks of harm or inconvenience. Ethical approval was obtained from Ethics committee of Ulster University and Nepal Health Research Council. Written informed consent was obtained.

RESULT

Four major themes are identified from the data.

Suffering of patients and families

The participants painted a picture of the extreme suffering of patients and families in rural Nepal when inflicted by diseases like cancer.

One MHW talked of a patient seeking euthanasia. “Patient feels that to live in such condition is a punishment. Life is extremely difficult, pain so severe that patient asks for medicine to end his life. Even I considered that this man will not live long, treatment is futile. Maybe euthanasia is an option?”

Another participant described his experience “I have seen patient shouting and crying in agony continuously, like the noise made by cattle. This hurts the family who think that it will be easier if death were to come earlier.”

They described how a malignant wound becomes infested with maggots and the difficulty for the family to cope with the situation. Poor economic condition of the families in rural area makes matters worse. Many cannot afford the expensive treatment and simply languish in the village.

Poverty has many other effects on overall care. Family members are unable to stay at home and care for the patient as no work means no money for food. Patients feel that they are burden to the family. Sometimes, the family also feels the same, especially when the disease becomes prolonged and protracted.

The thought of leaving behind young children increases the sociopsychological suffering of patients as they worry about their future. “I have seen both the father and mother die of HIV leaving behind their children with no one to support them.”

The MHWs described how the pain, anxiety about family and finances caused depression, not only in the patient but also in family members. Difficulty in accessing health care, due to difficult terrain and distances from the health posts made life even more difficult. They pointed out that even if they could get to the health-care facility, it was of little help as there was no medicine to control pain. They were aware that their own knowledge and skills in looking after patients with life-threatening illness was inadequate and lamented that if a doctor had been posted in the community, many patients would have symptom relief.

Helplessness and frustration felt by the mid-level health workers

Many of the MHWs voiced their helplessness and frustration in providing adequate care.

One participant described his experience “when patient is in extreme pain, the family becomes desperate. It breaks our heart to see such a situation. We feel it is our duty, so we console the family. We administer whatever analgesic we have. It is difficult to ask the family to pay for the medicine as they have already spent a lot. Many times, we give from our own pocket. How much can we give? We only go to see them in pain. I have been in such situations many times.”

Another member of the group shared his experience, “I have been looking after a lady who has not been able to eat anything. I have been giving her intravenous fluid on a regular basis. Her son asks me how can we continue to pay for this? I have been changing her catheter from time to time, this I pay from my own pocket.”

This illustrates not only their frustration but also their compassion and the wish to help patients even when there is hardly any facilities and supplies.

Another MHW also pointed out the lack of resources in the health center and admitted his lack of knowledge in this matter. “Villagers think we are great doctors, But we have no means to relieve their pain. This is very painful for me. We must admit without being ashamed that we lack proper knowledge and skills to look after such patients. We must build up our knowledge.”

If there are instances where they are looked on as great doctors, there are also times when the people in the community do not place much faith in them, which can be a source of frustration for MHWs. There were multiple references to the risk of being blamed if the patient were to die from their intervention. “There is a risk that if something were to happen to the patient, we could be blamed of negligence. The State has not assured us of our security.”

Many of the participants mentioned how looking after dying patients made them sad and the need for support for themselves to maintain their own wellbeing. One described her experience, “we were looking after a young patient. We did his dressings. He used to call us by our names. We became very close. He died so young. Oh, my God! I became very depressed. I felt I needed psychological support.”

They were aware of their own limitations and their vulnerability and the need to have support in such circumstances.

Sociocultural issues at the end of life

The health workers talked of the sociocultural issues that existed in the community which sometimes made life even more difficult for the patients.

They talked about how families made sure that the true diagnosis, especially of cancer, was not discussed with the patients. Discussion about prognosis was only done with the family. Many of the MHWs supported this practice of not letting the patient know about nearing death, citing the need to keep hope alive. “We know he has not long to live. His family also knows. But our moral does not allow us to tell the patient he is dying soon. He has a right to live. If he comes to know about his impending death, he might have heart attack. He might just die like that. So, we should tell him that treatment is going on, it will be all right.”

There were other MHWs who thought the patient should be told indirectly.“We should ask, “Is there anybody (any relative or friend) you want to see or is there any wish you must complete” He will take hint from this that things are not okay.”

They found it hard to talk to patients about dying. “I had a patient suffering from advanced cancer. No treatment was given. The doctors at the hospital had not explained his condition well to patient or family. The patient hoped to live. I just could not get the courage to tell him or his family that he was dying.”

They recognized their own limitations in managing hard conversations. “It is not like talking about infection. It is matter of death. How can we tell him he has not long to live? I just cannot do that but again we have to tell him.”

They also pointed out the discrimination faced by patients suffering from HIV and sometimes even cancer. One participant said, “talking about HIV, there is social neglect; society feel that the patient has acquired this through their own wrong doings and therefore it is right that they suffer.”

At times, even cancer is thought to be a communicable disease and people tend to stay away from such patients. “Many people consider cancer to be the Great Disease (Maharog) and stay away.”

“Many patients hide their disease from the family and present in advanced stage because of fear of being shunned by the community.”

Another MHW pointed out that patients tend to hide their disease because of fear of hospitals. Women will not want to be examined by male doctors. He discussed “my mother had breast lump. I convinced her to go to hospital for a check-up. She declined to go back for follow up.”

One MHW mentioned how pressure from neighbors and society forces the family to take patients to higher centers or tertiary hospitals in the cities even when cure is not possible.

Returning to their own land at the end of life seems to be very important to the people living in rural area.

“Most people like to come back to village to die. To be where one belongs seems to be important to many people.”

“People like to be among their loved ones at the last moment of life.”

The MHWs seemed to understand the local sociocultural context well and how these issues affected the life of the patients and their families.

Improving care at the community level

The participants were clear on how the care could be improved at the community level.

“We advise patients and families the best we can, but we could do it better if we had the training on how to communicate with such patients. We would like to learn the technique to deal with difficult situations.”

They emphasized on the need for training to be skill based and not only theoretical. “It is important to include practical training. We can then see what is reality. Learning is better when you see for yourself.”

“Training one health worker from health post will not solve the problem. It is important to educate all health workers; only then will it lead to behavioural change.”

One of them pointed out that required medicines should be made available after the training. “Only training is not enough; required medicines need to be made available. Otherwise we will still be in the same situation.”

Many MHWs seemed comfortable to use morphine if this was made available and if they were trained to use it within given guidelines. They were clear that at present they do not have the authority to prescribe morphine, but if they are given legal authorization, they were of the opinion they could use it.

“We are not allowed to prescribe Morphine at present but if the government gives the authority, we can use it.”

Some of them were hesitant to use morphine. “Using morphine could be risky. We have not used it before and moreover, it is not available.”

One MHW mentioned the need to include the care of patients with chronic illness. Apart from training health professionals working in the community, they voiced the need to educate the public to improve the care and change social behavior.

“Educating the public is important. They can also help look after such patients, at least do simple things, and can be good support in the community.”

“If public awareness program can be conducted in the community, this will help change social behaviour. People will seek help earlier and disease can be diagnosed in early stage.”

Many MHWs said that if there were care centers in the community; this will help in the care of patients with life-threatening illness especially for families who cannot afford not to go to work.

The need to improve their knowledge and skills was one of their main concerns along with the need to ensure essential medicine and supplies. They admitted their own lack of skills to handle difficult situations. Their emphasis on training for health workers was encouraging.

DISCUSSION

The above findings provide insight into the suffering of people living in rural area when inflicted by life-threatening illness and the difficulty faced by the health workers who look after them in a resource-constrained setting, compounded by poor access and poverty.

The first theme depicts the need for palliative care in rural Nepal where, at present, there seems to be little help for those suffering in pain and people, especially the poor, have no choice but to languish in the village. The suffering is heartbreaking for the family but also for the healthcare workers who witness them suffer but find themselves helpless to provide the much-needed care.

The helplessness felt by the health workers stands out clearly in this study. They want to help the patients and family but the lack of resources, particularly essential medicines for pain control, leaves them frustrated. This is similar to the experience of clinical officers in Uganda, who are akin to MHWs in Nepal, where they felt helpless to help the patient due to very similar reasons.[4]

The MHWs readily accepted their own lack of knowledge and skill to face such situations. They were ready to learn and improve their knowledge. Despite all the limitations, their desire to help the patients and family is clear and many times go beyond the call of their duty to provide care.

This study highlights the culture of not talking with the patient about death and dying. Such discussions are only held with the family members. This is in keeping with other studies in Nepal where most families will not allow the patient to be told.[5] Similar culture prevails in many other countries such as the United Arab Emirates,[6] Lebanon,[7] Japan,[8] Portugal,[9] Taiwan,[10] and Italy.[11] The findings in this study show that most Mid-level health workers (MHW) feel that it may not be appropriate to let a dying patient know that the end is near and most feel that it is important to keep hope alive. This mirrors the Nepalese cultural mindset where the families feel the need to protect their loved ones. This is not unique to healthcare professionals in Nepal, but similar feeling is seen in other countries like China.[12]

The MHWs raised the issue of social discrimination toward patients suffering from HIV. A study by Family Health International showed that in Nepal many consider HIV to result from immoral behavior, which was also described by one MHW in this study, leading to discrimination occurring within the family and in the wider community resulting in social isolation and huge emotional trauma.[13] This is not only a phenomenon unique to Nepal but also seen in many other countries such as the UK,[14] Tanzania, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Thailand,[15] Ghana,[16] and Nicaragua.[17]

Stigma and discrimination are not limited to HIV. Stigma attached to cancer continues to be a problem across the globe and negatively affects the efforts to increase cancer awareness.[18] This study also confirms that cancer-related stigma and discrimination results in further unnecessary suffering for patients in rural Nepal. It can be one of the reasons why many patients avoid seeking health care early resulting in a delay in diagnosis and poor prognosis.

Another factor for delay in seeking health care is fear of hospitals and especially for females, the fear of having to be examined by doctors of opposite sex. Elliot-Schmidt and Strong discuss that the response of rural people to illness or disability is related to productivity and will postpone seeking help until functionality is compromised to a state they can neither longer be productive nor do they like traveling to distant centers where they are likely to be misunderstood.[19] This difficulty seems to hold true in case of rural Nepal.

The desire to die in their own land with cultural ties amidst their loved ones seems to be important to rural people in Nepal. This is echoed by rural people in many other countries around the world such as Kenya,[20] Korea,[21] Scotland,[22] Australia,[23] Canada,[24] Sub-Saharan African countries,[25] China,[26] and Taiwan.[27] This is one compelling reason to develop palliative care in the local community.

Most MHWs were aware that Morphine is used for severe pain and its potential for abuse. They, however, felt they could use it if there was legal authorization from the Government and they had training and clear guidelines on how to use it. This is in contrast to the reluctance to use morphine by physicians mainly as a result of misconception held by the health professionals about addiction, adverse effect, and tolerance.[282930] Developing palliative care specialist MHW with training and legal authorization to use drugs like morphine is a modality that could pave the way to take palliative care to those living in the rural community. Such a model has been used successfully in Uganda where the law was changed in 2004 to allow specialist palliative care nurses and a cadre of health workers called Clinical Officers trained in palliative care to be able to prescribe morphine.[31]

The participants were clear on the need of training to improve their skills in looking after patients at the end of life, particularly skills in communication. They found talking about death and dying hard. They felt that patients with nonmalignant chronic illness also required similar care and through all the discussions, they shared experiences of such patients' suffering.

There were few limitations in this study. The first author did all the data analysis. Performing independent analysis by two or more authors tends to reduce bias; however, member checking with six of the twenty-eight participants who had taken part in the focus group discussion provide trustworthiness to the study. Another limitation was that the participants were all working in one district of Nepal when the discussion was held and may not represent the view of health workers in other rural parts of Nepal. Inviting health workers from different parts of Nepal would have been costly and was not considered due to lack of funds. This problem was overcome using purposive sampling method, inviting participants with variable years of experience with the view that those with many years of experience would have worked in many different districts of Nepal, thus bringing views and experience from all over Nepal. The participants had worked in 20 districts altogether bringing experience from various part of Nepal.

This study has several implications for the development of palliative care in Nepal. It clearly identifies the need to develop palliative care in rural Nepal. Although this study does not quantify the need, it brings forth the pain and suffering of patients with life-threatening illness. The wish of patients to be at home with their family at the end of life emphasizes the need to develop palliative care service at their doorsteps. It also highlights the gap in the knowledge and skills of the MHW in looking after patients at the end of life and identifies areas in which training should focus such as pain control and communication skills. A more quantified needs analysis in rural areas of the country may help to estimate the need of palliative care services and burden of problem.

CONCLUSION

This study provides the views of MHW with experience of serving patients with life-threatening illness in a rural community. It depicts the pain and suffering of patients and their family due to lack of medical support compounded by poverty, difficult access and at times, social discrimination. The health workers face many challenges in caring for the patients not only due to lack of resources but also lack of their own knowledge and skills in treating complex symptoms and having a difficult discussion about death and dying. There is, however, a willingness to learn and improve the care for such patients in the community through training and system improvement.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Palliative care development: The Nepal model. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:573-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health Services, Ministry of Health, Government of Nepal. Annual Report 2015-2016. Available from: http://www.dohs.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/DoHS_Annual_Report_2072_73pdf

- A method of analysing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Educ Today. 1991;11:461-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of a modular HIV/AIDS palliative care education programme in rural Uganda. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2008;14:560-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Informing patients about cancer in Nepal: What do people prefer? Palliat Med. 2006;20:471-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Should doctors inform terminally ill patients? The opinions of nationals and doctors in the United Arab Emirates. J Med Ethics. 1997;23:101-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Truth telling in the case of a pessimistic diagnosis in Japan. Lancet. 1999;354:1263.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis disclosure in a Portuguese oncological centre. Palliat Med. 2001;15:35-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer diagnosis and prognosis in Taiwan: Patient preferences versus experiences. Psychooncology. 2004;13:1-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evolution of truth-telling attitudes and practices in Italy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2004;52:165-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chinese oncology nurses' experience on caring for dying patients who are on their final days: A qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:288-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2004. Stigma and Discrimination in Nepal: Community Attitudes and the Forms and Consequences Persons Living with HIV/AIDS. Available from: http://www.un.org.np/sites/default/files/report/tid_188/stigma%20and%20discrimination.pdf

- HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: Accounts of HIV-positive Caribbean people in the United Kingdom. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:790-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acomparison of HIV/AIDS-related stigma in four countries: Negative attitudes and perceived acts of discrimination towards people living with HIV/AIDS. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:2279-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Measuring HIV- and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination in Nicaragua: Results from a community-based study. AIDS Educ Prev. 2013;25:164-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- The concept of well-being in a rural setting: Understanding health and illness. Aust J Rural Health. 1997;5:59-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- A good death in rural Kenya? Listening to Meru patients and their families talk about care needs at the end of life. J Palliat Care. 2003;19:159-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors influencing preferences for place of terminal care and of death among cancer patients and their families in Korea. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:565-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- What influences decisions around the place of care for terminally ill cancer patients? Int J Palliat Nurs. 2005;11:541-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- 'I don't want to be in that big city; this is my country here': Research findings on aboriginal peoples' preference to die at home. Aust J Rural Health. 2007;15:264-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- La belle mort en milieu rural: A report of an ethnographic study of the good death for Quebec rural francophones. J Palliat Care. 2010;26:159-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- End of life care in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. BMC Palliat Care. 2011;10:6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The preference of place of death and its predictors among terminally ill patients with cancer and their caregivers in China. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;32:835-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient preferences versus family physicians' perceptions regarding the place of end-of-life care and death: A nationwide study in Taiwan. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:625-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physician attitudes and beliefs about use of morphine for cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1992;7:141-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment and knowledge in palliative care in second year family medicine residents. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;14:265-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Barriers to effective cancer pain management: A review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18:358-68.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uganda: Delivering analgesia in rural Africa: Opioid availability and nurse prescribing. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:547-51.

- [Google Scholar]