Translate this page into:

Assessment of Private Homes as Spaces for the Dying Elderly

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Aim:

This study makes an assessment of end-of-life care of the elderly in private homes in Kolkata, West Bengal, India.

Participants and Methods:

Primary data were collected from private homes which supported elder care through observation and semi-structured interviews with primary family caregivers of the elderly.

Results:

The study finds that the major factors preventing private homes from providing adequate care to the elderly were architecturally inadequate housing conditions, paucity of financial support, and scarcity of skilled caregivers. Besides, considerable neglect and domestic abuse of the elderly was also found in some private homes. In addition, the peripheral location of private homes within public health framework and inadequate state palliative policy, including stringent narcotic regulations, accentuated the problems of home care.

Conclusion:

The study concludes by questioning the rhetoric of private homes as spaces for the dying elderly in Kolkata and suggests remedial measures to improve their capacity to deliver care.

Keywords

Care of the elderly at private homes

continuum of care

end-of-life care of the elderly

palliative care

public health

INTRODUCTION

India presently houses nearly 103.8 million persons who are above 60 years of age, a rise of 27.2 million from the past census record of 2001.[1] Although its end-of-life care (EoLC) situation has persistently received poor ranking in the quality of death index, commissioned by Lien Foundation,[23] it has failed to evoke sufficient academic interest to explore the gaps associated with EoLC settings such as private homes. Policies for the elderly in India such as the National Policy for Older Persons (1999), the National Policy for the Senior Citizens (2011), and the National Policy for the Health Care of the Elderly (2011) have largely overlooked the importance of private homes as dying spaces. Private homes have been looked at from the perspective of aging, rather than dying, and inter-state differences in demographic features – basic EoLC infrastructure, political context, and ideology – which impose special challenges in providing care at private homes to the dying elderly have not received adequate and equal attention. As a result, some states like Kerala have done well, while others have shown no improvement in EoLC delivery.

Kolkata, the metropolitan city of West Bengal in India, has a high share of elderly population. However, the health delivery system of Kolkata is not geared for elder care and is reflective of the poor health infrastructure in the entire state of West Bengal. West Bengal is considered one of the rapidly aging states in India.[4] The expected lifespan of the people in West Bengal is projected to remain higher (at 69 years, in 2006–2010) than the national average. A survey to explore the status of the elderly in West Bengal revealed that 10.6% and 12.7% of the surveyed elderly (N = 1275) in urban and rural areas of West Bengal, respectively, required full/partial assistance in at least one activities of daily living (ADL) domain and indicated the growing incidence of loss of ability for ADL at higher age. The survey also showed low functionality in instrumental ADL (IADL).[5] The elderly in West Bengal suffered from higher locomotor disability and psychological stress compared to the other six states in the study.[6] In another large-scale survey,[7] it was found that, in West Bengal, nearly two-thirds and one-third of the sample population of 1173 people above 50 years of age reported requiring assistance in ADL and IADL, respectively, thereby making the state rank highest in disability as compared to five other Indian states that were surveyed. The survey further revealed that West Bengal has the highest burden of acute morbidities among the elderly (26%), and nearly two-thirds of the respondents in the survey (66%) reported suffering from chronic ailments.[5] Notwithstanding such high prevalence of morbidities, utilization of hospital facilities is considerably low among the elderly in West Bengal. It was estimated that 4.3% of their respondents in West Bengal, aged above 50 years, did not receive any treatment when needed, thereby showing a fairly high unmet need for health care.[7] Although the exact reason for not seeking hospital care could not be ascertained from either of the above-mentioned reports, it might be inferred that apprehension related to high out-of-pocket expenditure made many avoid hospitalization. In state-wise comparison, West Bengal ranks highest in out-of-pocket expenditure on medicine and lowest in investment for long-term care. Poor health insurance coverage of elderly of the State (<1% in forms of public or private insurance schemes) explains the huge financial burden.[7] The State has also made very little progress in palliative and EoLC. It has so far neither evolved a policy on palliation nor implemented the recent amendment to narcotics and drug policy with respect to availability of morphine. None of the government hospitals have yet worked out a palliative program based on private homes. Currently, palliation at private home is provided by few nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), but they appear to be ill-networked and mostly operate with funds from international bodies. Unfortunately, a very meager amount of funding is allocated for palliation at private homes. There is also considerable variation in modes and services of the NGOs with greater need for standardization or at least consumer information on the available choices.

The overall health delivery system of West Bengal has evoked considerable concern over quality issues, resulting in a considerable outmigration for treatment to southern states of India. In a study conducted on 78 secondary hospitals of West Bengal, the State performed poor in the technical efficiency measure with only 26 of them, mostly located near Kolkata, found to be relatively efficient. Unavailability of doctors, underutilization of the services of support staff, and infrastructure deficiencies in handling emergency cases were identified as the greatest obstacles. These factors cumulatively make secondary hospitals situated in the rural districts operate as mere transit points for emergency cases before they are rushed to specialized hospitals in Kolkata.[8]

The above features provide a strong justification for assessing private homes as settings for supporting long trajectory of dying, associated with old age. While private homes can emerge as congenial care setting for those who are aging and dying, little is known of their capacity to meet this challenge when placed within a relatively ill-functioning health system. In the absence of good health delivery system, it is pertinent to ask: how do private homes figure as spaces for the dying elderly in Kolkata?

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Design

This study uses an exploratory research design to elicit qualitative information about conduciveness of private homes for EoLC of the elderly.

The focus of this paper is not to assess the efficacy of the care delivered, but to concentrate on the context in which it is delivered.

Locale of the study

The study was conducted in Kolkata and its outskirts. Kolkata has a large number of public and private hospitals, but only few hospitals such as Calcutta National Medical College and Hospital, Tata Medical Centre, Kolkata, and Saroj Gupta Cancer Centre and Research Institute have recently initiated palliative care on a very small scale. These are all hospital-based initiatives and are not home based. Private homes in Kolkata are served by few NGOs such as Eastern India Palliative Care, Kosish - the Hospice-Kolkata Chapter, Kolkata Palliative Care Initiative, Tribeca Care, and Arunima Hospice. Collectively, some of these organizations provide free services to approximately only 15/25 patients per month. The palliative care services at private homes by the NGOs are highly fragmented in nature: with an NGO providing physician support, another providing ambulatory/volunteer support and yet another providing logistic/nursing support. In other words, private homes are not supported by comprehensive long-term care services.

Sampling

The contact information of the private homes supporting elderly patients was collected from the NGOs after obtaining ethics committee approval from the NGOs. Family members were contacted over telephone to seek verbal consent for data collection, followed by a written consent during home visit. Out of 276 private homes contacted, only 17 consented for providing access. However, in the final count, only 13 were retained because during the home visit the family caregivers were found to be sick, demented, having symptom management crisis, or refused to provide written informed consent.

Data collection and analysis

The fieldwork was completed in a year starting from October 2014. Data were obtained through observation and semi-structured interview with the family caregiver. The semi-structured interview was developed for eliciting information in a conversational and flexible style as per the convenience of the family caregiver, who shared her/his perceptions on varied topics ranging from housing conditions, caregiving experiences, care relationships, and experiences of receiving palliative care. Information obtained from the family caregiver was further validated by referring to their clinical histories kept with the NGOs. Each private home was visited 4–7 times for data collection. After completion of each home visit, the audio-taped responses were transcribed. The responses were grouped thematically under broad headings and analyzed through content analysis techniques.

RESULTS

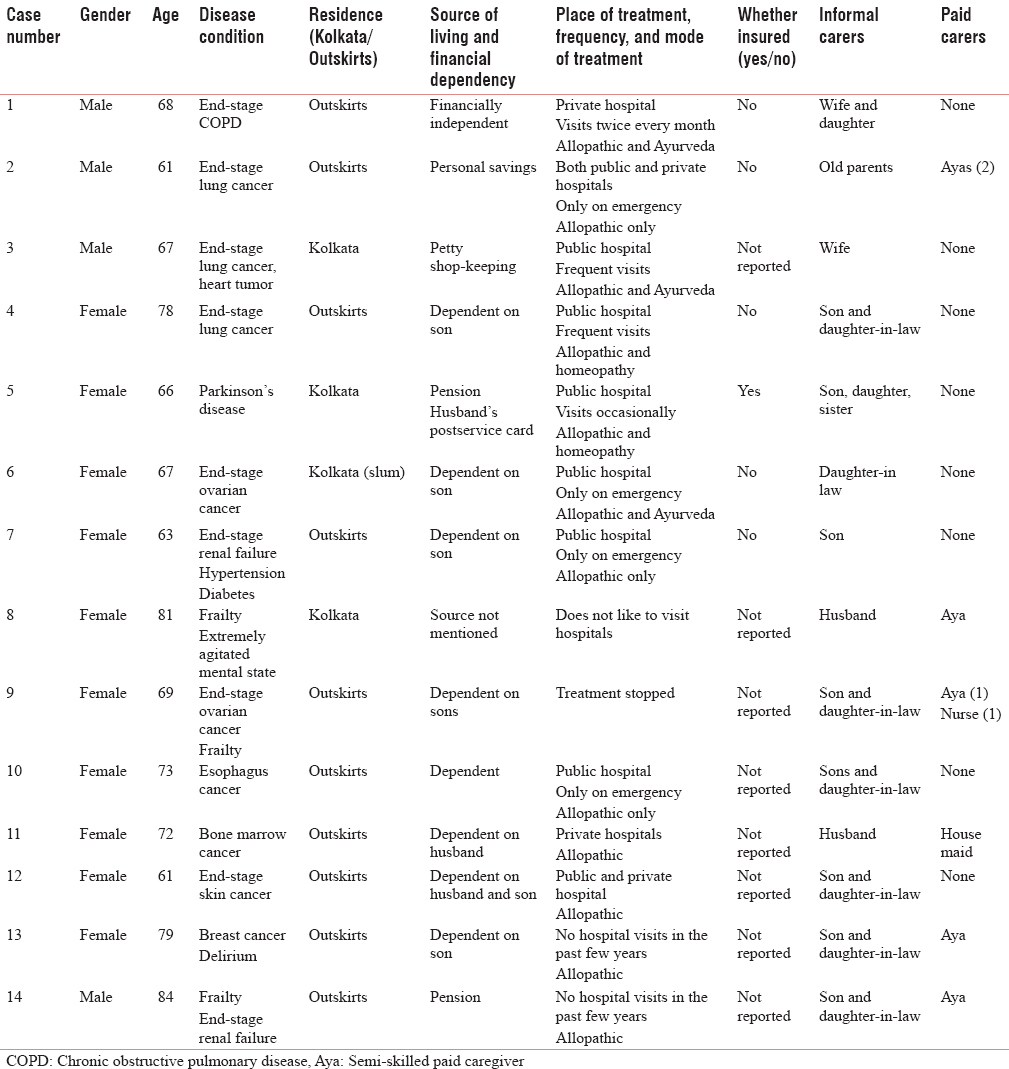

Among the 13 private homes, 14 elderly patients were investigated in the study. Five private homes supported the elderly suffering from noncancer chronic diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), renal failure, and dementia, while the rest of the private homes supported elderly suffering from cancer. All the private homes belonged to poor income groups with annual income ranging from Rs. 100,000 to Rs. 500,000. Only one private home had elderly covered by health insurance, while the medical expenses of the elderly in other private homes were paid through personal savings or pension of the elderly or by their spouse and/or children. Six private homes took support for few hours/week from paid caregivers – nurses or semi-skilled maids (ayas) – to provide care/assistance for the family caregiver in providing care to the elderly. The Demographic characteristics and the care received by the Elderly is presented in Table 1.

The findings also highlighted the following major features of private homes supporting elderly in Kolkata.

“Physically inadequate” housing conditions of the private homes

In response to the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing (2002), many countries have promoted elderly care at private homes through home modifications, preferential housing facilities to allow co-habitation with children, and have introduced many assistive technologies for the elderly.[9] These recommendations, though presented under the “Active Ageing” framework, have also worked to the advantage of the dying elderly and their carers. In contrast to these provisions, the idea of elderly care at private homes in Kolkata appears somewhat challenging given the architecturally constrained situations. The housing conditions of the private homes in Kolkata were found to be physically inadequate to provide support to the dying elderly. Three private homes were found to be extremely impoverished, dark, poorly ventilated, and with crammed spaces. Twelve private homes were found to have inadequate living space, water, energy, ventilation, and sanitation facilities. Seven private homes had roofs leaking in the rooms where the elderly stayed.

Few cases have been described below as an illustration:

A 73-year-old female elderly with esophagus cancer (case 10), with meager family income, stayed with her husband, two sons, one daughter-in-law, and two grandchildren in a very small private home, with no separate rooms. It was no better than a sheltered place with tin roof and unplastered brick walls. Some spaces were demarcated by old clothes, sarees, torn bedspreads, bamboo sticks, and asbestos sheets to ensure some privacy to the residents. The patient stayed in an empty space outside the house, under the sun for the entire day and was taken inside the home during night or rain. The private home was located in a wetland (nonresidential area) and therefore was secluded as there were no neighbors and no means of transportation.

There was another case where a 78-year-old female elderly with end-stage lung cancer (case 4) rented out one of the rooms (among two rooms) in their asbestos-roofed house to fetch money for treatment. Her husband, a construction labor, had constructed the house, all by himself. Her two sons – both carpenters – and their families occupied other rooms. The patient stayed in a small corner of the house and her husband came home only at night and slept in the kitchen.

In still another case, a 68-year-old male patient with end-stage COPD (case 1) was virtually trapped in the top floor of the house. His doctor recommended an elevator to help him go to the ground floor, but installing one was not feasible.

Care in private homes is deeply gendered

Many scholars in Western settings have considered home care to be deeply gendered with the bulk of care work done by women – mostly daughters and daughters-in-law.[101112] Indian studies have also highlighted this feature.[1314151617] This is also confirmed in the present study where women are the primary caregivers for the dying elderly in private homes. With most of the patients bedridden and others having episodic pain or other symptoms, a huge care workload at private homes fell upon the women, mostly daughters-in law. The surveyed private homes could hardly afford paid caregivers such as nurses (1/13) or even semi-skilled maids (5/13). Some family members reported difficulty in getting a nurse or semi-skilled maids; many lacked the competence and aptitude to care for the dying elderly at private homes.

Private homes can be abusive

Dying for the elderly at private homes is not merely gendered, it is often undignified. In one private home, a 61-year-old male patient with end-stage lung cancer (case 2) lived with his elderly parents, while his wife stayed in a different location with the children due to conflict with her in-laws. The patient's father wanted his daughter-in-law to come back to their home to take care of her husband and had requested the NGO team to persuade his daughter-in-law to return. However, the patient's mother became hysterical on hearing this and promised to take care of her son all by herself. It thus seems that, entrenched within conflicting mother-in law and daughter-in-law relationships, dying can be extremely stressful.

Care at private homes under such conditions may also degenerate to outright abuse as follows: Dr. X, an 84-year-old physician, suffering from renal problems and other comorbidities (case 14), and his 79-year-old wife, suffering from breast cancer and dementia (case 13), were found to be strapped to their beds with cords (both hands and legs were tied) in separate rooms. He was in depression while she was in a state of delirium. Both of them were in abject neglect and poor nursing. During the home visit, the old lady was found in her soiled diaper and was completely undressed (just covered with a bedspread) and had bed sores, despite having a paid semi-skilled maid, aya, to look after her.

The daughter-in-law, who was the principal family carer, admitted that the burden of continuous caregiving for two seriously sick persons was proving to be challenging, exhaustive, at times depressing, and stressful. She was frustrated because of unfamiliarity with caring tasks. She said that she strapped the elderly to the bed to prevent falls.

The above case, besides highlighting the lack of dignity of the dying at private home, also shows caregivers’ stress–a feature found in many other studies as well.[1819]

Burden and challenges of caregiving at private homes

The burden of caregiving at private home was accentuated by poor access to information, counseling, and lack of supportive services. A “strange” case of total confusion and chaos was found by the researcher during home visit, who was unaccompanied by the NGO on that day.

The case pertains to a middle-class educated family in Kolkata looking after their mother – a 63-year-old lady with renal complications, hypertension, and diabetes (case 7). She had undergone dialysis and has been undergoing treatment for the past 4 years at different hospitals, throughout India. Recently, she had settled in a small rented apartment in Kolkata with her son, who was pursuing his doctoral studies at the same place. Of late, she had been getting frequent infections and had been admitted to the hospital several times in Kolkata, each time for 3–4 weeks.

While speaking to the family member over the phone to seek verbal consent, the researcher heard someone crying with pain in the background. On inquiry, the patient's son confirmed that his mother was in intense pain. He was very confused and was reluctant to contact any doctor, since their previous appointments with the doctors had not yielded positive outcomes.

After a long deliberation, the son decided to leave Kolkata altogether and proceed to Chennai for treatment. However, he allowed the researcher to visit their home for data collection, and during the home visit, he sought help from the researcher to find a paid caregiver, who could accompany and stay with his mother in Chennai. He had to return to Kolkata after admitting her and thence, proceed to Germany for his studies. During the home visit, the patient was found to be crying in pain and had not taken any medical support. Instead, she expressed total disgust with medical facilities in Kolkata and preferred to bear pain rather than undergoing any treatment, whatsoever. After the home visit, the patient's son dropped the researcher to the bus stand. On the way, the researcher met a carpenter known to her (case 4's younger son). The patient's son told the researcher to inquire if the carpenter could send his wife/daughter/neighbor to accompany his mother to Chennai and stay with her during her treatment and suggested a fee of Rs. 10,000 each month for caregiving.

Now, it so happened that the carpenter earned only Rs. 9000/month and was willing to accompany the patient to Chennai for the extra thousand, provided the railway fare was paid by the family. To this, the son agreed and asked him to get ready for the departure. The researcher insisted that the carpenter was not well known to her and obviously lacked training and skills to look after a critical patient. She also warned that the idea of hiring him appeared rather risky. However, the son continued to proceed with his plan…

Home care sans palliation

The burden of private home is aggravated by lack of a systematic palliative program. Unlike many countries abroad which are supported by State-supported palliative network,[20] private homes in Kolkata exist within an uncoordinated, fragmented health delivery system. There is little provision for respite care or alternative structures when care at private homes becomes burdensome. In the study, the patients came to know about home visits at private homes from the NGO kiosks at three major locations in the city and therefore it is uncertain as to how many missed this information. The possibility of the exclusion of large percentage of the elderly is quite likely. Moreover, these home visits have several logistic limitations, distance being one of them. Home services could be availed by private homes which are located in/outskirts of Kolkata. Simultaneously, care at private home was also affected by poor discharge procedures at hospitals. Three of the patients who were very old and bore multiple morbidities were insensitively discharged with no supportive arrangements. This reflects a poor quality of EoLC management as well as a lack of continuum of care. All the private homes had patients in pain and anxiety. Confusion and turmoil prevailed, and there was clearly a need for the psychological and spiritual support.

DISCUSSION

Centering private homes for EoLC requires some important provisions which seem to be absent in Kolkata. The burden of both acute and chronic morbidity among the dying elderly in the sampled private homes suggests the need for relocating homes in a continuum of care with hospitals on one hand, and other long-term arrangements on the other hand. The study reveals that providing EoLC at private homes is difficult and challenging for many family carers and results in significant stress and burden. Some carers even seemed lost and helpless in the absence of adequate information and skills to deal with dying patients; there is clearly a need to strengthen private home care with more trained workforce and nursing services. While most countries abroad supporting home care have considered carers as an important resource, currently, none of the programs run by the State address their needs adequately.

Home care was also found to be deeply gendered and marked by conflict between elderly patients and their caregivers, possibly accentuated by the latter's limited capacity to deal with health crisis at the end of life. The study, though sparse, shows that life's endings within private homes may often take place amidst conflicting, abusive relationships. This issue needs a special attention given the fact that the reported level of elderly abuse in West Bengal is considered to be higher than that of other states.[9] There is thus a need for institutional support of the dying elderly in the form of old-age homes or other long-term structures which could provide more choices to such vulnerable elderly.

The study shows that, although many private homes supported elderly suffering from cancer, most were receiving palliation at the end stage—a feature which goes against the current practices of good care management. Thus, it appears that care provision at private homes has not been worked out through proper identification and need assessment. Most of the family caregivers have elicited help in an erratic manner. If identifying service providers is difficult, reaching those in needs is equally problematic for NGOs. In short, home-based palliation needs to be supported through proper organizational strategies and such NGOs also need support and nurturance by the State.

Home-based palliation is also impeded by stringent rules centering on the availability of morphine and other narcotic drugs in West Bengal. All the cancer patients covered in the study reported to be in pain. The study also reports frequent and emergency hospitalization among the sample households without any dedicated or familiar doctor on contact, except in one case. To reduce emergency hospitalization, these private homes need to be linked through a public health network; hospital discharge planning too needs to take cognizance of private home's capacity to address the needs of the dying. Currently, a few old-age homes and new retirement settlements have emerged between home and acute care settings, but it is not clear how effective they are as spaces for the dying.

Finally, the study raises critical concern about private home's potential for EoLC for the urban poor. Most of the private homes supporting elderly in the sample had no insurance or financial and social support. EoLC in such homes needs to be supported through a proper service mix, involving both health and social services. The State has around 33% of the total elderly population below poverty line[21] and this suggests that many of them might need social security for the carers if home care is encouraged. It may be mentioned that major social security schemes for the elderly in West Bengal have been introduced fairly recently. In 2008, the Community Based Primary Health Care Services for urban population covering groups both below and above poverty line was commissioned. Many Central government schemes such as the National Programme for Health Care of the Elderly and medical mobile programs have not yet been fully operational with broad population coverage. Some schemes involving equal sharing by the Centre and the State governments such as the Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme provide a measly Rs. 400/- for people in the age group of 60–79 years and Rs. 1000 for people aged 80 years and above.

CONCLUSION

The study, though not representative, brings out a few limitations of private homes as settings for EoLC of the elderly. Structurally, private homes in the study are too fragmented and architecturally constrained. Caregivers are burdened, and there is a huge care deficit, particularly for home-based palliation. Given the fact that Kolkata and the entire state of West Bengal have a huge elderly population with poor health profile and a health delivery system which is inadequate, it is difficult for private homes to assure good quality of dying. The study suggests the need for more state provisions for home modifications, developing EoLC as part of a good public health framework, and locating private homes in a continuum of care with adequate palliative and social support.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by the Ministry of Human Resource Development.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The present research would not have been possible without the support of Radhika Singh, Dr. Abhijit Dam from Kosish - the Hospice, Dr. Sanghamitra Bora and all the team members of Eastern India Palliative Care. All of them had substantially helped in the data collection procedure. The 1st author would like to thank each of them individually.

REFERENCES

- 2013. CensusIndia.gov.in. Census of India - Presentation on Age Data. Government of India. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/

- 2015. The Economist Intelligence Unit. Lien Foundation: Quality of Death Index: Ranking Palliative Care Across the World 2015. Available from: https://www.eiuperspectives.economist.com/sites/default/files/2015%20EIU%20Quality%20of%20Death%20Index%20Oct%2029%20FINAL.pdf

- 2010. Economic Intelligence Unit. Lien Foundation: The Quality of Death: Ranking End-of-Life Care Across the World 2010. Available from: http://www.graphics.eiu.com/upload/eb/qualityofdeath.pdf

- 2013. SRS Statistics. Estimates of Fertility Rate. Government of India. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/SRS_Reports_2013.html

- 2012. Report on the Status of Elderly in Select States of India, 2011. United Nations Population Fund. Available from: http://www.isec.ac.in/AgeingReport_28Nov2012_LowRes-1.pdf

- 2014. The Status of Elderly in West Bengal, 2011. United Nations Population Fund. Available from: http://www.countryoffice.unfpa.org/india/drive/Book_BKPAI_WestBengal_20thFeb2014 lowres.pdf

- 2013. Study on Ageing and Adult Health-Wave 1: India National Report. World Health Organisation. Available from: http://www.C:/Users/Suhita/Downloads/SAGEIndiaReport%20(2).pdf

- 2014. Analysing Efficiency of Government Hospitals in West Bengal. Available from: http://www.ideasforindia.in/article.aspx?article_id=361

- 2010. HelpAge, India. Report on Elder Abuse in India. Available from: http://www.helpageindia.org/pdf/surveysnreports/elderabuseindia2010.pdf

- Experiences of long-term home care as an informal caregiver to a spouse: Gendered meanings in everyday life for female carers. Int J Older People Nurs. 2013;8:159-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Applying feminist, multicultural, and social justice theory to diverse women who function as caregivers in end-of-life and palliative home care. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7:501-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship quality and elder caregiver burden in India. J Soc Interv Theory Pract. 2012;21:39-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perceived caregiver burden in India: Implications for social. J Women Soc Work. 2009;24:69-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Older persons, and caregiver burden and satisfaction in rural family context. Int J Gerontol. 2007;21:216-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health status and caregivers of elderly rural women. Indian J Gerontol. 2003;17:157-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- On being old and female: Some issues in quality of life of elderly women in India. Indian J Gerontol. 2001;15:333-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Burden among caregivers of mentally-Ill patients: A rural community-based study. Int J Res Dev Health. 2013;1:29-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Burden of caregiver of psychiatric in-patients. Orissa J Psychiatry. 2008;16:37-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global Atlas for Palliative Care at the End of Life. Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance. World Health Organisation. Available from: http://www.who.int/nmh/Global_Atlas_of_Palliative_Care.pdf

- Poverty Target Programs for the Elderly in India with Special Reference to National Old Age Pension Scheme. Chronic Poverty Research Centre Working Paper, 2008-2009. Available from: http://www.chronicpoverty.org/uploads/publication_files/CPR2_Background_Papers_Kumar-Anand.pdf