Translate this page into:

Prevalence of Depression in Breast Cancer Patients and its Association with their Quality of Life: A Cross-sectional Observational Study

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death among women worldwide. In India, the incidence rate of breast cancer is found to be 25.8/10,000 females. The statistics for Kerala, India, is 30.5 in urban areas and 19.8 in rural areas. Cancer and treatment-related symptoms are major stressors in patients with breast cancer undergoing treatment for the disease. Depression is a prevalent psychological symptom perceived by breast cancer patients, and it also impacts the quality of life (QOL) in these patients. We aimed to assess the prevalence of depression and its association with QOL of patients with breast cancer undergoing treatment for breast cancer.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional study enrolled 270 patients diagnosed with breast cancer (>18 years) and undergoing active treatment in a tertiary care center in Kerala, India. Depression was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition Research guidelines. We measured the QOL and its domains using the WHOQOL-BREF.

Results:

The average age of women in research was 53.56 years. Of the 270 patients, 21.5% had depression. Among patients with depression, 22% had moderately severe to severe depression. Patients with depression experienced overall a poor QOL. Twenty-two patients reported their overall QOL was “poor” and 34 patients reported to be dissatisfied with their health. There was an association between depression and domains of QOL. Patients with depression had lower scores in all domains when compared to those without depression.

Conclusion:

Depression and poor QOL is common among breast cancer patients.

Keywords

Breast cancer

depression

quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide and the leading cause of cancer death in women, with roughly 1.4 million new breast cancer cases and 458,000 deaths in 2008.[1] It is considered as a terrifying disease due to a high mortality rate, its impact on self-image and sexual relationship.[2] The different modalities for treatment of primary breast cancer include surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and hormonal therapy, all four of which can be used alone or as combination.[3] Surgery is the primary treatment for breast cancer, whereas chemotherapy and radiotherapy are adjuvant therapies commonly used after primary treatment to inhibit metastasis and enhance long-term survival rates.[4]

The number of women who survive breast cancer has significantly increased in recent years due to the advances in detection and treatment. However, the aggressiveness of the treatment exposes the patients to various treatment side-effects. In fact, cancer and treatment-related symptoms can be major stressors in a patient with breast cancer who is undergoing treatment for the disease.[5] Therefore, addressing the impact of breast cancer and its treatment on long-term outcomes is an important issue.[6]

Studies have shown that nearly a third to a half of female breast cancer patients are likely to experience psychological distress.[7] Among women with breast cancer, the prevalence of depression ranges from 1.5% to 50%, depending on the sample, and particularly the definition of depression and method of assessment.[89]

Quality of life (QOL) has been used as a primary outcome measure in recent years. It is a complex multidimensional assessment of the physical, psychological, and social well-being of individuals.[10]

The adverse effects of breast cancer or treatment-related symptoms and types of treatment have been associated with different domains of QOL.[11] High levels of depression in breast cancer can also influence coping with cancer and QOL adversely.[12]

Even after an effective treatment of the physical disease, such psychological distress may persist and accompany the patient for a long period, which has a negative impact on the patient's QOL.[1314] In most oncology settings, the treatment focuses only on the physical symptoms whereas the psychological distress is often overlooked.

Understanding these common psychiatric disorders and associated psychosocial factors found in breast cancer patients can help to plan for effective treatment of these patients and may result in more treatment success. In this study, we aimed to study the prevalence of depression in patients with breast cancer who are undergoing treatment and its association with their QOL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Aims and objectives

To study the prevalence of depression among breast cancer patients undergoing treatment and to correlate its association with their QOL.

Study design and sample

This cross-sectional, observational study was done in a tertiary care hospital in Kerala, with a comprehensive cancer care unit including pain and palliative care and psycho-oncology units. This study was conducted from August 2014 to August 2016. The study population included patients aged above 18 years who were diagnosed with breast cancer and are undergoing surgery or chemotherapy or radiotherapy or a combination of therapies. Patients with a family history of mood disorder or other psychiatric disorder were included in this study.

Patients with current psychiatric disorders or cognitive deficits and with hearing or visual impairments were excluded from the study. The sample size was calculated with a prevalence of 22% reported by Hassan et al. in a study conducted among Malaysian breast cancer patients.[15] The sample size was estimated to be 270 with 95% confidence and 20% allowable error. The patients were recruited through convenience sampling.

Research outcomes

-

To determine the presence of depression among adult breast cancer patients

-

To determine whether the presence of depression is associated with their overall QOL, overall satisfaction with health and different domains of QOL.

A total of 300 patients were selected, out of which 11 did not give consent and 19 were excluded due to missing data.

Data collection and measurements

After obtaining informed consent, a semi-structured pro forma was used for recording the sociodemographic and clinical details.

Depression was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) which is a self-administered 9-item depression scale derived from the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. The PHQ-9 [Annexure 1] is used to screen for depression over a period of 2 weeks and is also a reliable and valid measure of depression severity. The average sensitivity/specificity for PHQ-9 was found to be 88%/78% in a systematic review of specificity and sensitivity of instruments used to diagnose and grade the severity of depression. The minimum acceptable sensitivity/specificity using the structured interview as the reference was 80%/80% for structured interviews and 80%/70% for case-finding instruments.[16] A validated and published Malayalam version of the PHQ-9 was used in this study which can be downloaded for free from the website for PHQ screeners.

Patients with a score above 5 on PHQ-9 were interviewed by a postgraduate resident and a consultant psychiatrist using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition Research guidelines to diagnose depression.

The WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire was used to assess the QOL among all the patients. It contains a total of 26 items. A time frame of 2 weeks is indicated in the assessment. The WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire [Annexure 2] was used to assess the QOL among all the patients. It is possible to derive four domain scores. The four domain scores denote an individual's perception of QOL in each particular domain. The four domains are physical, psychological, social relationship, and environmental. Domain scores are scaled in a positive direction (i.e., higher scores denote higher QOL). The mean score of items within each domain is used to calculate the domain score. Mean scores are then multiplied by 4 to make domain scores comparable with the scores used in the WHOQOL-100. There are also two items that are examined separately: Question 1 asks about an individual's overall perception of QOL and question 2 asks about an individual's overall perception of their health. A validated and published Malayalam version of the WHOQOL-BREF was used in this study[17] after obtaining permission.

Statistical analysis

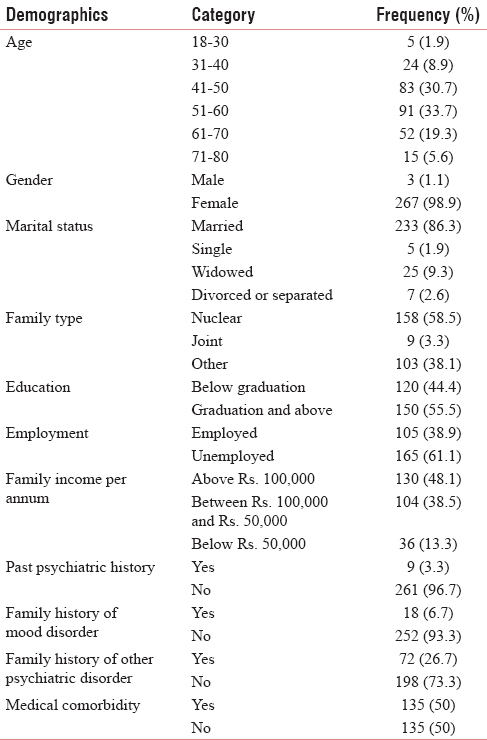

The data obtained was tabulated on Microsoft Excel sheet, and the analysis was done on Social Package for the Social Sciences software version 20 (SPSS Statistics is a software package used for logical batched and non-batched statistical analysis). Frequency tables for sociodemographic details including age, gender, marital status, type of family, education status, employment status, family income per annum, history of depression, family history of mood disorder, medical comorbidity, and depression were generated. The numerical variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables were expressed as frequency. To obtain the association between QOL and depression, Chi-square test was applied. To obtain the mean comparison of different domain scores with depression, independent two-sample t-test was applied. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent printed in Malayalam or English was obtained from the patients before the interview. The study was approved by Dissertation Review Committee of Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences and the Ethics Committee.

RESULTS

A total of 270 breast cancer patients were studied, of which 267 were female, and three were male. The average age was 53.56 (±10.4) years. A large number of patients were married (86.3%) and lived in nuclear families (58.5%). More than half of the patients had a graduate or postgraduate degree (55.5%), were unemployed or retired (61.1%). One hundred and thirty (48.1%) had an annual family income of Rs. 100,000 or above, 104 had an income between Rs. 100,000 and Rs. 50,000 (38.5%), and 36 had an income <Rs. 50,000 (13.3%). Majority of them did not have a history of depression (96.7%) or family history of mood disorder (93.3%). Half of them had medical comorbidity. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the study population.

Out of 270 patients, 58 (21.5%) had depression and 212 (78.5%) did not. Among those with depression, 17 had mild depression (6%), 19 had moderate depression (7%), 12 had moderately severe depression (4%), and ten had severe depression (4%) as shown in Figure 1.

- Distribution of depression.

Depression was higher in the age group 18–40 years and lowest among those above 60 years but the association was not statistically significant.

Depression was higher among the low socioeconomic group than those the high or middle socioeconomic group, but the comparison was not statistically significant.

The average scores (mean ± SD) of physical, psychological, social relationships, and environmental domains in WHOQOL-BREF were 12.30 ± 1.68, 12.81 ± 1.72, 14.17 ± 2.75, and 14.37 ± 2.12, respectively [Table 2].

In response to the question “how would you rate your QOL?,” 22 (8.1%) patients reported that their QOL was “poor,” 58 (21.5%) reported “neither poor nor good.” The proportion of patients who reported their QOL as “poor” was higher in depressed patients than those without depression.

To the question “how satisfied are you with your health?,” 34 (12.6%) reported “dissatisfied” to “very dissatisfied” and 78 (28.9%) reported “neither satisfied not dissatisfied.” Patients reporting their overall satisfaction with their health as “dissatisfied” or “very dissatisfied” were more among the depressed group than the group without depression.

Overall, QOL was significantly worse in patients with depression and comparison of all four domains of QOL with depression was also statistically significant [Table 2].

DISCUSSION

The present study was conducted in tertiary care hospital in Kerala among breast cancer patients undergoing active treatment. The prevalence of depression among this population was found to be 21.5%. Similar prevalence of depression was reported in a Malaysian study among breast cancer patients by Hassan et al. where 22% had depression.[15] In this study, 7% had moderate depression and 8% had moderately severe to severe depression, and 6% had mild depression. In a population-based cohort study of 1400 women diagnosed with stage 0–IV breast cancer in China, 13% fulfilled the criteria for clinical depression at 18 months postdiagnosis as assessed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale.[18] The presence of depression could be related to many reasons. Most women after being diagnosed with breast cancer find it difficult to come to terms with the diagnosis followed by dealing with the uncertainty of the illness and imagining the worst. The results of the present study showed that depression was common among the study population; however, it is often overlooked or goes undiagnosed. Symptoms of breast cancer treatment such as tiredness and pain are also causes for feeling depressed[19] since these symptoms become a hurdle in their day-to-day activities. Making family, work, and financial adjustments in anticipation of treatment and/or periods of being unwell could be also contribute to the distress in these women. Another major concern is their appearance. Breast cancer and its treatment can change the way a woman thinks and feels about her whole body, her femininity, her self-esteem, and the way she behaves. Mastectomy or loss of hair due to chemotherapy and early menopause could be a serious threat to a woman's image of herself. Fertility and libido may also be affected by treatment of breast cancer with chemotherapy or hormonal therapy.[20] One of the major concerns for these women is the response and support from their partners, children, and family member which has a positive influence on their psychological health. The present study revealed that patients with depression experienced poor overall QOL than those without depression. The previous studies based on cross-sectional data have shown that depression is inversely related to QOL among breast cancer patients and survivors.[212223] Chen et al. reported that QOL was significantly and independently associated with depression in their study among Chinese breast cancer patients.[18] Another study among Chinese breast cancer patients also showed that patients with depression experienced overall a poorer level of QOL.[24] In our study, depression was significantly associated with all four domains of QOL.

The group with depression had lower scores in all domains compared to the group without depression implying that the impairment in the physical health, psychological, social, and environmental QOL of breast cancer patients with depression is associated with higher psychological burden. In a study by Yen et al.,[25] QOL of breast cancer patients with malignant tumor was compared to those with benign tumors using the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire and found that in the malignant group, participants with depression had a significantly poorer QOL on physical, psychological, social, and environmental dimensions. Kluthcovsky and Urbanetz assessed the QOL of breast cancer patients using the WHOQOL-BREF and reported that breast cancer patients had poorer QOL in physical, psychological, and social relationships than the comparison group. However, in their study, no difference was found in the environmental domain.[26] So et al., in a similar cross-sectional study using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy for Breast Cancer, reported that depression had a significant effect on all domains of QOL except social/family well-being.[24] A recent review showed that psychological distress not only predicted QOL but also the overall survival rate in breast cancer patients and that counseling, supportive care, and exercise benefit these patients by improving QOL.[27]

Early diagnosis and intervention may be beneficial to these patients. According to a study by Ell et al., 30% of 472 women receiving cancer care had depression, but only 12% of these women were receiving medication, and only 5% reported seeing a counselor.[28]

In Eastern societies, higher stigma attached to mental illness would delay or preclude psychiatric treatment.[29] This will cause cancer patients with depression to be less likely to accept treatment. The goals of planning a psychosocial intervention in the Indian breast cancer context would be to support the patient's ability to cope with the stress of treatment, helping them to tolerate short-term loss for long-term gain, and to assist in symptom management.[3031] Identification of the subset of women at risk is one such way forward, followed by targeted intervention that could be in the form of patient education and counseling.

Limitations

The inherent bias in convenience sampling means that the sample is unlikely to be representative of the population being studied. The selected study sample was undergoing either surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or a combination of treatments. Since it was not a homogenous sample undergoing the same mode of treatment, the influence of a particular treatment modality on depression was not assessed. Tumor staging was not done for the study sample; hence, the effect of cancer stage on depression was not assessed. Those patients with depression would benefit from pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy which was beyond the scope of this study.

CONCLUSION

Findings of this study show that depression which is quite treatable is a common psychiatric morbidity faced by breast cancer patients. As depression is proven to be associated with QOL, it is important to improve the sensitivity of screening for depression and to make psychiatric services available for patients with breast cancer. Hence, prompt intervention including psychosocial programs and a referral to psychiatrist if necessary are warranted.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1893-907.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and psychosocial factors of anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90:2164-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Contemporary Issue in Breast Cancer: A Nursing Perspective (2nd ed). Sudbury: Jones and Bartlett; 2004.

- 2002. National Cancer Institute. Adjuvant Therapy for Breast Cancer: Questions and Answers. Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Therapy/adjuvant-breast

- Physical symptoms/side effects during breast cancer treatment predict posttreatment distress. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34:200-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Why and how to study the fate of cancer survivors: Observations from the clinic and the research laboratory. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2136-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial responses in breast cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2007;23:71-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Instgr. 2004;32:57-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of depression in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review of observational studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:2649-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- The quality of life and self-efficacy of Turkish breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:449-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of quality of life of women with breast cancer. Glob J Health Sci. 2016;8:52792.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depression and anxiety levels in woman under follow-up for breast cancer: Relationship to coping with cancer and quality of life. Med Oncol. 2010;27:108-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer over 4 years: Identifying distinct trajectories of change. Health Psychol. 2004;23:3-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychological distress two years after diagnosis of breast cancer: Frequency and prediction. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;40:209-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anxiety and depression among breast cancer patients in an urban setting in Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:4031-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Which instruments to support diagnosis of depression have sufficient accuracy? A systematic review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69:497-508.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation of WHOQOL-BREF in Malayalam and determinants of quality of life among people with type 2 diabetes in Kerala, India. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2016;28(1 Suppl):62S-9S.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of depression and its related factors among Chinese women with breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:1128-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics and correlates of fatigue after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1689-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of menopausal symptoms among women with a history of breast cancer and attitudes toward estrogen replacement therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2737-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fatigue and depression in disease-free breast cancer survivors: Prevalence, correlates, and association with quality of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:644-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychological morbidity and quality of life in Australian women with early-stage breast cancer: A cross-sectional survey. Med J Aust. 1998;169:192-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between quality of life and mood in long-term survivors of breast cancer treated with mastectomy. Support Care Cancer. 1997;5:241-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anxiety, depression and quality of life among Chinese breast cancer patients during adjuvant therapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14:17-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life, depression, and stress in breast cancer women outpatients receiving active therapy in Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:147-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: A comparative study. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2015;37:119-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is quality of life data predictive of the survival in cancer patients? A rapid and systematic review of the literature. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2009;2:1-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depression, correlates of depression, and receipt of depression care among low-income women with breast or gynecologic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3052-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caregiver responses to symptoms of first-onset psychosis: A comparative study of Chinese-and Euro-Canadian families. Transcult Psychiatry. 2000;37:255-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and their combination on quality of life in depression. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2011;19:277-89.

- [Google Scholar]

- Conditioned emotional distress in women receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:108-14.

- [Google Scholar]

Annexure 1: Patient Health Questionnaire 9. http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/en/english_whoqol.pdf

Annexure 2: WHOQOL BREF. http://www.phqscreeners.com/select-screener/36

WHOQOL-BREF

The following questions ask how you feel about your quality of life, health, or other areas of your life. I will read out each question to you, along with the response options. Please choose the answer that appears most appropriate. If you are unsure about which response to give to a question, the first response you think of is often the best one.

Please keep in mind your standards, hopes, pleasures and concerns. We ask that you think about your life in the last four weeks.