Translate this page into:

Continuing Professional Development for Volunteers Working in Palliative Care in a Tertiary Care Cancer Institute in India: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study of Educational Needs

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Context:

Training programs for volunteers prior to their working in palliative care are well-established in India. However, few studies report on continuing professional development programs for this group.

Aims:

To conduct a preliminary assessment of educational needs of volunteers working in palliative care for developing a structured formal continuing professional development program for this group.

Settings and Design:

Cross-sectional observational study conducted in the Department of Palliative Medicine of a tertiary care cancer institute in India.

Materials and Methods:

Participant volunteers completed a questionnaire, noting previous training, years of experience, and a comprehensive list of topics for inclusion in this program, rated in order of importance according to them.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Descriptive statistics for overall data and Chi-square tests for categorical variables for group comparisons were applied using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 18.

Results:

Fourteen out of 17 volunteers completed the questionnaire, seven having 5–10-years experience in working in palliative care. A need for continuing professional development program was felt by all participants. Communication skills, more for children and elderly specific issues were given highest priority. Spiritual-existential aspects and self-care were rated lower in importance than psychological, physical, and social aspects in palliative care. More experienced volunteers (>5 years of experience) felt the need for self-care as a topic in the program than those with less (<5-years experience) (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

Understanding palliative care volunteers’ educational needs is essential for developing a structured formal continuing professional development program and should include self-care as a significant component.

Keywords

Continuing professional development

Educational needs

Palliative care

Volunteers

INTRODUCTION

People with serious and probably life-limiting medical illnesses like cancer require empathy as well as competence from their healthcare providers. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines give algorithms on distress management and palliative care.[12] The 2009 National Consensus Project on Quality Palliative Care emphasises the importance of psychological, social, and spiritual care and support for patients with advanced cancer and their families.[3] The Institute of Medicine report on Cancer Care for the Whole Patient addresses the preparation of existing taskforce for this crucial service in psycho-oncology.[4] To this end, specific educational programs have been developed, chief among these being Education for Physicians in End of life Care (EPEC), End of life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC), Dissemination of End-of-Life Education to Cancer Centers (DELEtCC), and Survivorship for Quality Cancer Care.[56789] Otis-Green et al., (2009) have conducted the Advocacy in Clinical Excellence (ACE) project, a transdisciplinary program for psychologists, social workers, and spiritual care professionals.

The role of voluntary sector in oncology and palliative care is very important.[10] Volunteers not only play a role in fundraising and advocacy but also are involved in direct patient care activities all over the world, especially in the US and Europe.[11] The altruistic role of volunteers adds an emotional dimension to formal medical caregiving.[12] They give their time to the patients and their families, adding comfort at the emotional level. The roles of volunteers in specialist care are distinct and variable ranging from professional to advocacy.[13] A survey of volunteers in specialist adult palliative care services reported that they worked in day care (90%) and bereavement services (79%) mainly.[14] It was reported that volunteers participated in a range of activities like serving meals, greeting visitors to the hospice/palliative care units, giving emotional support to patients and their families, sharing in the hobbies, running errands, driving patients to hospital appointments, and sitting by the patients in the final hour. This survey also reported that certain services were entirely volunteer-led, for example, complementary/alternative therapies, professional beauty/hairdressing, and faith-based care. In a study conducted by Godfrey et al., on Prevention of Delirium (POD) program, volunteers participated in this process, engaging mainly in re-orientation of the patients, which decreased incidence of Delirium.[15]

While this is true of adult services, the situation in pediatric palliative care services is different.[16] Another study found that 68% of volunteers were involved in counselling and volunteers in 42% of organizations belonged to mental health profession.[14] In a randomized controlled trial, senior volunteers were useful in delivering a reminiscence and creative activity intervention.[17] The role of the volunteers trained in palliative care has extended to general hospitals too.[12] Volunteers found work in this setting a positive and satisfying experience, although there were different challenges and uncertainties. The contribution of volunteers in palliative care in India has been reported.[18] Volunteers, thus, significantly contribute to patient care by providing a wide range of services across a range of settings, in different countries of the world, in palliative care and beyond.

In order that volunteers are able to fulfil their varied and sensitive roles, orientation and training modules related to different aspects of their work are essential. A recent comparative study on volunteers in palliative care across seven European countries has looked at education and training of this workforce.[19] Training programs for volunteers both in oncology and palliative care are mostly orientated around communication skills[20] and organized mainly prior to them beginning their work in the field of palliative care. Training programs for volunteers in palliative care in India too follow this pattern.[21] Continuing professional development is a mandate for all healthcare workers to keep abreast of recent advances and updates. Volunteers working in palliative care have to deal with suffering, death and dying, and are involved in general and bereavement counselling. Hence, they should also undergo continuing professional development programs. There are many training programs and manuals for volunteers in palliative care in India but studies in the area of continuing professional development programs for this group of healthcare staff are lacking.

The purpose of this paper is to conduct a preliminary assessment of educational needs of volunteers in palliative care in order to set up a structured formal comprehensive continuing educational program for this group. The aims are 1) to determine the domains, sub domains, and their order of importance to be included in the program, 2) to assess the learning methods preferred and suggestions made, and 3) to look for any group differences in volunteers based on type of qualification and number of years of volunteering experience.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Population and setting

The target population is the group of volunteers working in the Department of Palliative Medicine in a tertiary care oncology institute in India. These volunteers, having undergone training program in communication skills and psychosocial issues conducted by the palliative care department, work as counsellors in the clinic. Their role entails focus on communication skills, exploring psychosocial and spiritual issues, and providing emotional support to patients and their caregivers attending the clinic.

Those volunteers who agreed to participate in the study and were literate in English were included. There were no specific exclusion criteria.

Interventions

A questionnaire was specially prepared for this purpose to note the type of qualification, number of years of volunteering experience in palliative care, need for a continuing education program, topics and subtopics for inclusion (covering communication skills, physical, psychological, social, and spiritual-existential aspects of palliative care, self-care, learning methods preferred, and suggestions, if any). Participants completed this questionnaire. The study design is an observational cross sectional survey.

Outcomes and measures

-

Primary outcome measure: Comprehensive list of topics and subtopics for inclusion in this program.

-

Secondary outcome measures: a) Group differences in volunteers based on years of training experience and type of previous training, b) learning methods preferred rated in order of importance, and c) noting suggestions made by the participants.

Statistical considerations

Descriptive statistics for overall data and Chi-square tests for categorical variables for group comparisons were applied using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 18.

RESULTS

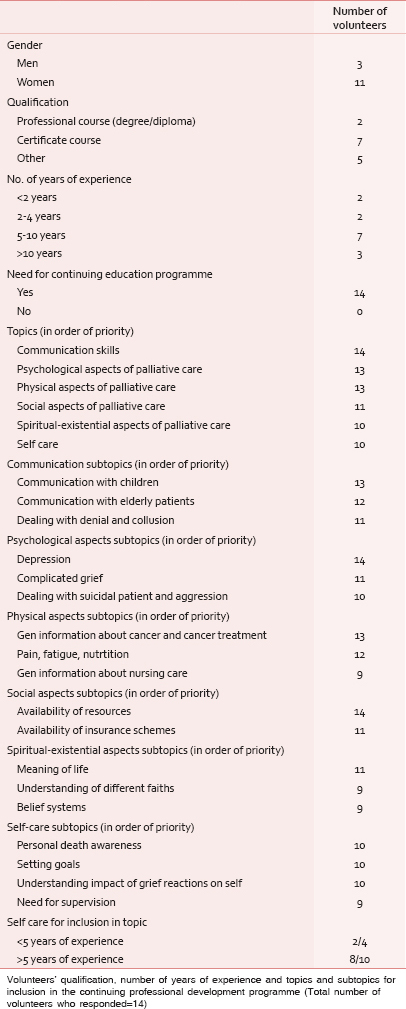

Fourteen out of 17 volunteers participated, the response rate being 82.3%. Eleven of 14 respondents were women (79%). Two respondents had a professional degree or diploma qualification in social sciences and seven had certification training in counselling in palliative care. Seven volunteers had 5–10 years and three had more than 10-years experience in voluntary work in palliative care. All volunteers agreed that there was a need for continuing education program [Table 1]. Topics in order of priority were (1) communication skills, (2) psychological aspects, (3) physical aspects, and (4) social aspects of palliative care. Spiritual-existential aspects and self-care were given 5th and 6th place in rating, respectively.

In communication, important issues in order of priority given were dealing with children, working with elderly, and addressing denial and collusion. The subdomains in physical aspects were general information about cancer and treatments, pain, fatigue, nutrition, and general nursing care in that order. Depression and complicated grief were felt of higher priority than dealing with aggression and suicidal ideation under the domain psychological aspects. The subtopics included in social aspects were availability of resourcesfirst and insurance schemes second.

Spiritual-existential aspects included meaning of life as 1st in priority, followed by understanding of different faiths and belief systems. Self-care subtopics were rated from higher to lower rank as personal death awareness, goal setting, impact of grief on self, and need for supervision.

The learning methods preferred were lectures, case studies, and group discussions, in that order. Other methods like journaling, self-reflection exercises, and homework assignments were rated lower. Suggestions were made about timing for the program, use of role plays, dealing with feelings of over involvement, and information about medications and medical notes.

Volunteers with more than 5 years of experience felt the need for self-care for inclusion as a topic in the program than those with less than 5 years of experience (P = 0.046). There were no group differences found in volunteers’ educational needs depending on type of qualification.

DISCUSSION

The response rate was 82.3%, which was higher than in a previous study.[20] Seventy-eight percent of respondents were females, slightly higher than 66% in ACE project.[22] The number of volunteers with a professional degree or diploma qualification was small in our study, which is just a representation of volunteers who work in the clinic. Half of them had 5–10-years experience. In the ACE project, the average years of experience was 11 but that study was targeted at professionals in psychology, social work and spiritual care.[22] Understandably, communication skills training, being a highly valued part of any educational program in oncology and palliative care, was given highest priority by our study participants, even though the focus here was on continuing professional development, rather than basic training needs. The topics in later order of importance were psychological, physical, and social aspects.

Spiritual concerns of patients, especially at the end of life, need to be understood.[23] Recognition of one's own spirituality is essential for working with palliative care patients and hence, meaning of life and belief systems are important. This has a role in preventing physicians’ stress and burnout.[2425] However, spiritual-existential aspects of palliative care were rated lower in importance by our study participants. A probable explanation maybe that volunteers’ sense of spirituality and meaning in life are already quite well-ingrained, considering the nature of their work, purpose, and sense of altruism. The other possibility could be that the participants considered their spiritual-existential beliefs as personal and preferred to work through these at an individual level, without having to be part of the course curriculum. As our country is a secular state, an understanding of different faiths is essential for a greater relatedness with patients and their caregivers, This subtopic, therefore expectedly, was given 2nd priority in this domain.

Self-care is the buffer, which stands between a satisfactory and productive work experience and compassion fatigue with burnout in oncology workers, and especially in palliative care.[26] Self-awareness is an integral component of self-care and can be enhanced by strategies as Balint groups, meditation, and reflective writing practice.[26] Self-care, though along with spiritual-existential aspects found important for inclusion by 71% of respondents, was rated 5th or 6th in priority list. In the components of self-care as a domain, the need for supervision was rated lowest in the sub domains. Interestingly, volunteers with more than 5-years experience found self care as an important topic for inclusion than those with less than 5-years experience. Self-care was an integral component in the ACE project.[22] Previous literature on training programs for palliative care volunteers in India has not noted about self-care or found an association with years of experience.[27] Self-care cannot be overemphasised and needs to be included in any training program, especially one directed at continuing professional development for volunteers in palliative care. Staff support group sessions aimed at self-care can be regularly incorporated in weekly palliative care team meetings and self care practices should be actively encouraged.

Dealing with children and elderly require special skills and competence and therefore, given higher priority than dealing with denial or collusion, in the communications subdomains. The latter are handled quite often by the volunteers in our clinical work and hence, probably given last preference. As volunteers are working in an oncology setting, it is understandable that general information about cancer and treatments, symptom management, and nursing care are prioritised in that order, respectively. This is reflected in Otis-Green et al.,'s project of excellence in pain and symptom management by social workers, which was very successful.[28]

The domain of social aspects in palliative care needs to be understood in our country context. The absence of a uniform healthcare system increases financial burden in caring for patients with life-limiting illnesses and consequently causes strain on the caregivers. Hence, knowledge about availability of resources and information about different types of health insurance schemes of benefit for patients belonging to varied socio-economic status attending the hospital are very important.

Though volunteers are adept in understanding and acknowledging emotions and empathy, identifying and working with clinical depression and complicated grief are challenging issues, which come to forefront once they start active patient-care-related activities after basic training. These topics, being integral components in psychosocial issues[2021] are, therefore, rated higher in priority needs in psychological aspects domain.

Learning methods preferred by volunteers reflected adult learning styles espoused in education.[29] Some of the suggestions made related to learning more about psychological and self-care issues regarding feelings of over-involvement. These concerns can be taken up in detail in structured continuing professional development programs, which we are advocating.

The study had limitations of having a small number of participants and being hospital palliative care clinic based.

The implications are that based on the baseline information on participant needs and priority, the content of the curriculum has to be devised with use of appropriate teaching strategies. The continuing professional development program needs to be implemented with evaluation measures for process and outcome at multiple time points in what is planned as a rolling course, with incorporation of feedback and suggestions in the subsequent programs.

CONCLUSION

This study identifies the need felt by all volunteers working in palliative care for continuing professional development programs to update their knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Self-care needs to be an integral component of such programs as the group may underestimate the crucial role of self-care assessment and practice. Evidence-based continuing professional development programs are essential for this group for sustaining a caring and competent workforce in palliative care and excellence in delivery of palliative care in India.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge the contribution of the volunteers who participated in this study.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Distress management. Clinical practice guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2003;1:344-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network). Palliative care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:1284-309.

- [Google Scholar]

- The National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care Clinical Practice Guidelines Domain 8: Ethical and legal aspects of care. HEC Forum. 2010;22:117-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- IOM. Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs. [Internet] 2008. Psycho-Oncology. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/pon.1478

- [Google Scholar]

- Professional education in end-of-lofe care: A US perspective. J R Soc Med. 2001;94:472-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oncology End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium training programme: Improving palliative care in cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:801-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- End-of-life nursing education consortium: 5 years of educating graduate nursing faculty in excellent palliative care. J Prof Nurs. 2008;24:352-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Disseminating end-of-life education to cancer centers: Overview of program and of evaluation. J Cancer Educ. 2007;22:140-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparing professional staff to care for cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:98-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- A narrative literature review of the contribution of volunteers in end-of-life care services. Palliat Med. 2013;27:428-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Volunteers trained in palliative care at the hospital: An original and dynamic resource. Palliat Support Care 2014:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding the role of the volunteer in specialist palliative care: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13:3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Volunteers in specialist palliative care: A survey of adult services in the United Kingdom. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:568-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Developing and implementing an integrated delirium prevention system of care: A theory driven, participatory research study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:341.

- [Google Scholar]

- Paediatric palliative care: A review of needs, obstacles and the future. J Nurs Manag. 2015;23:4-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Can senior volunteers deliver reminiscence and creative activity interventions? Results of the legacy intervention family enactment randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48:590-601.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of pain and palliative care services on patients. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17:24-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Volunteers in Palliative Care - A comparison of seven European countries: A descriptive study. Pain Pract 2014

- [Google Scholar]

- Italian consensus on a curriculum for volunteer training in oncology. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;12:39-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Training community volunteers and professionals in psychosocial aspects of palliative care. Indian J Palliat Care. 2005;11:53-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- An overview of the ACE Project-advocating for clinical excellence: Transdisciplinary palliative care education. J Cancer Educ. 2009;24:120-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. Gerontologist. 2002;42:24-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mid-career burnout in generalist and specialist physicians. JAMA. 2002;288:1447-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Professional education in Psycho-social oncology. In: Holland JC, Breitbart WS, Jacobsen PB, Lederberg MS, Loscalzo MJ, McCorkle, eds. Psycho-oncology (2nd ed). New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. p. :610-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Self-care of physicians caring for patients at the end of life: “Being connected. a key to my survival”. JAMA. 2009;301:1155-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psycho-oncology in India: Emerging trends from Kerala. Indian J Palliat Care. 2006;12:34-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Promoting excellence in pain management and palliative care for social workers. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2008;4:120-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Learning Styles and Learning Spaces: Enhancing Experiential Learning in Higher Education. Acad Manag Learn Educ. 2005;4:193-212.

- [Google Scholar]