Translate this page into:

The Attitude of Iranian Nurses About Do Not Resuscitate Orders

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Do not resuscitate (DNR) orders are one of many challenging issues in end of life care. Previous research has not investigated Muslim nurses’ attitudes towards DNR orders.

Aims:

This study aims to investigate the attitude of Iranian nurses towards DNR orders and determine the role of religious sects in forming attitudes.

Materials and Methods:

In this descriptive-comparative study, 306 nurses from five hospitals affiliated to Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (TUOMS) in East Azerbaijan Province and three hospitals in Kurdistan province participated. Data were gathered by a survey design on attitudes on DNR orders. Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) software examining descriptive and inferential statistics.

Results:

Participants showed their willingness to learn more about DNR orders and highlights the importance of respecting patients and their families in DNR orders. In contrast, in many key items participants reported their negative attitude towards DNR orders. There were statistical differences in two items between the attitude of Shiite and Sunni nurses.

Conclusions:

Iranian nurses, regardless of their religious sects, reported negative attitude towards many aspects of DNR orders. It may be possible to change the attitude of Iranian nurses towards DNR through education.

Keywords

Advanced care directive

Do not resuscitate orders

End of life care

Nurses

Palliative Care

Resuscitation

INTRODUCTION

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is defined as the administration of chest compression typically along with artificial respiration, cardiac defibrillation, and intravenous drugs.[1] The successfulness of CPR is dependent on a patients’ medical status and the prognosis of underlying problems and comorbidities.[2] Previous studies report that between 7.6 and 21.7% of patients are discharged from hospital after CPR attempts.[3]

Half a century ago do not resuscitate (DNR) orders were introduced into medical literature.[1] DNR may be defined as not to initiate CPR as the times of cardiac or respiratory arrest.[4] The DNR order is normally only used when the patient's prognosis is very poor.[1] Globally, DNR orders are commonplace in many Western countries’ contemporary clinical practice.[15] However, this practice is not yet fully understood or implemented in many other countries.[14] DNR orders may raise strong emotions in the non-western society.[1]

Despite many similarities, there are also many differences between Western region and Asian-Pacific on the provision of end of life care.[6] Culture and religion are two important factors in the perception of society about end of life issues.[7] Many studies in Western countries have demonstrated that, despite some differences, many health professionals in United States,[8] Finland,[9] Sweden, and Germany[10] hold positive attitudes toward DNR orders. In contrast, other studies report that many critical care nurses in the United States have misconceptions about DNR orders.[4]

Few studies have investigated the attitude of Muslim healthcare providers towards DNR orders. These studies reported that there are differences between the attitude of healthcare providers in Turkey[11] and Saudi Arabia[12] toward DNR and many of healthcare providers in Singapore have many misconceptions about DNR orders.[13] All previous studies that investigated the attitude of Muslim healthcare providers about DNR orders were conducted in the Sunni population[111213] and the attitude of Shiite healthcare providers were not investigated. There are many differences between the two main sects of Islam, Shiite and Sunni, but they have many similarities about the death and care of patients who die.[14] But, it is necessary to assess Shiite healthcare providers. This study aims of to investigate the attitudes of Iranian nurses regarding DNR orders and determine the role of religious sects in such attitudes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This descriptive-comparative study was conducted between June and December 2012. Five hospitals affiliated to Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (TUOMS) in East Azerbaijan Province (EAP) and three hospitals in Kurdistan province (KP) that are affiliated to Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences (KUMS) were selected as the study setting.

Nurses in the eight selected hospitals who had at least 6 month clinical experience and providing direct patient care formed the study sample. The numbers of nurses in five hospitals affiliated to TUOMS who met the inclusion criteria were 410 nurses and the numbers of nurses in KUMS’ affiliated hospitals were 420 nurses. All of the nurses in TUOMS affiliated hospitals were Shiite Muslim with Azeri cultural background and all of nurses in KUMS affiliated hospitals were Sunni Muslim with Kurdish cultural background. According to pilot study the sample size of 320 nurses was determined. Then according to the number of nurses in each hospital the number of samples determined for each hospital. Then the sample was obtained from each hospital by simple sampling method. Finally, the data of 306 nurses were collected.

The instrument used has two parts. The first part is a researcher's prepared checklist that assessed demographic and profession related characteristics of participants. The second part is a questionnaire designed by Dunn (2000) used to assess attitudes towards DNR.[15] This questionnaire consisted of 25 items based on 5 point-Likert scale from completely disagree (score 1) to completely agree (score 5).

For use in this study, the English form of the questionnaire was translated and back translated by two independent English translators. Then the content validity of the questionnaire was determined by 12 academic staff from TUOMS and some minor changes made according to their comments. Then, the reliability of translated questionnaire was determined by Cronbach's alpha after pilot study on 25 nurses (0.82).

The study was approved by Regional Ethics Committee prior to data collection. A list of all nurses who met the inclusion criteria of the study was obtained from the nursing office of each hospital. Then, the researchers contacted each nurse and provided a brief description of the study and invited them to participate in the study. At that time, informed consent was obtained. The questionnaire was provided to all nurses after short study overview. Some nurses answered the questionnaire during their shift and others took the questionnaire and returned during next shift. A total of 320 questionnaires were distributed and 306 were collected.

Data analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software (version 13, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The demographic and profession-related characteristics of nurses were analyzed using descriptive statistics including frequency, percent, mean, and standard deviation (SD). Independent sample t-test was used for comparison the attitudes of nurses from TUOMS and KUMS.

RESULTS

Analyzing the demographic and profession-related characteristics of participants showed that most of participants were female (77%), married (60%), educated at baccalaureate of science level (94%), and worked in hospitals affiliated to KUMS (61%). Nurses identified that their current clinical practice area was an intensive care unit (34%), medical wards (25%), surgical wards (22%), and emergency departments (19%). The mean age of nurses was 31 years (SD = 6 years) and the mean duration of work experience was 7 years (SD = 6 years).

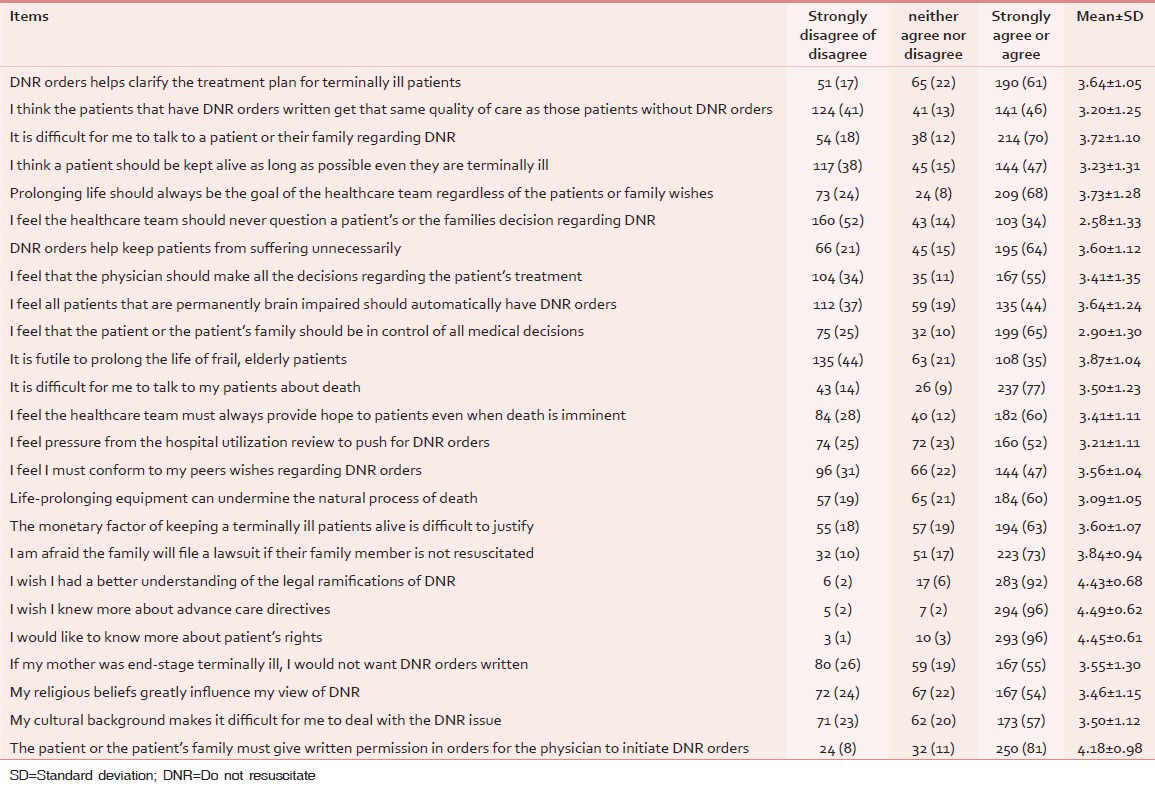

The response to each item of attitudes toward DNR questionnaire is reported in Table 1. As demonstrated in this table, for some items nurses had a positive attitude towards DNR orders, including their tendency and willingness to learn more about DNR orders; considering the autonomy of patients, caregivers, and their family members in DNR decision making; and the role of healthcare providers in questioning of patients, caregivers, or their family members about DNR orders. In contrast, in many other key items, participants reported their negative attitudes towards DNR orders. Participants reported they are not willing to talk to patients, caregivers, or their families about DNR orders; prolonging life regardless wishes of patients or their families and inspiring hope to terminally patients are the duty of healthcare providers; DNR orders do not prevent unnecessary suffering; physicians should make all decisions about DNR orders; and DNR orders may cause legal problems for them.

The attitude of nurses in TUOMS and KUMS hospitals was compared. This analysis showed that only in two items the attitude of nurses related to these universities was different. In one item, nurses affiliated to TUOMS hospitals reported more positive attitude toward this idea that healthcare team should never question a patient's or the families decision regarding DNR (P = 0.04). In another item, nurses in KUMS reported that, in comparison to nurses in TUOMS, they must conform to their peers wishes towards DNR orders (P = 0.01).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first investigating the attitude of Iranian nurses toward DNR orders and examined the role of religious sects in the forming of attitudes. The results demonstrate that, in spite of positive attitudes on some items, Iranian nurses have a negative attitude toward DNR orders in many key items of attitude on DNR questionnaire.

In an extensive review of literature, there are only a few studies that have investigated the viewpoints of Muslim healthcare professionals about DNR orders. In one study Al-Mobeireek (2000) reported that only 16% of Saudi physicians suggested DNR for previously healthy elders.[12] In another study, Iyilikci et al., (2004) reported that 66% of Turkish anesthesiologists had initiated oral or written DNR orders.[11] In another study conducted in Singapore, Varon et al., (2004) identified that healthcare providers have many misconceptions about DNR orders.[13] These studies highlight that the practice of DNR varies amongst Muslim healthcare providers in different countries.

There were no previous studies identified that investigated the viewpoint of Iranian healthcare providers toward DNR orders. It should be noted that in some studies the attitude of Iranian nurses[1617] and medical students[18] towards euthanasia was investigated. In two studies Moghadas et al., (2010)[16] and Rastegari-Najafabadi (2010)[17] reported that half of Iranian nurses agreed with euthanasia. In another studies the half of Iranian medical students reported their positive attitude toward euthanasia.[18] It is interesting to compare the results of these studies with the results of the current study. According to all Islamic sects, all types of euthanasia and assisted suicide are forbidden.[19] In contrast, the DNR orders is not contradictory with basic Islamic rules.[14]

Islam holds life as holy[14] and recognizes that death is a predictable part of human life.[20] Muslims believe that death does not happen apart from by God's authorization.[21] Thus, treatments does not have to be provided if it merely prolongs the final stage of terminal illness.[20] Withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in such instances may seem as allowing death to take in its natural course.[21]

So, the negative attitude of Iranian nurses about DNR orders is not justified by considering religious issues. It should be noted that most positive attitude of participants is about their wish to learn more about different aspects of DNR orders. In contrast, many of the participants reported that their religious beliefs greatly influence their view of DNR. So, it is possible that one important reason for negative attitude of participants about DNR orders may be lack of knowledge about DNR orders. Similarly, previous studies showed that Iranian healthcare providers have limited information about many ethical dilemmas.[22]

Another important finding of this study is that in only two items of attitude on DNR questionnaire there was a statistical difference between Shiite and Sunni nurses. Although, there are many differences between different Muslim's schools of thoughts, but they are united regarding their views on death and dying.[14] Similarly, this study found that there was no difference among attitude of nurses from two important sects of Islam, Shiite and Sunni, regarding DNR orders.

The results of this study have implications for practice. Results showed that Iranian nurses have negative attitude toward many key aspects of DNR orders. This means that Iranian healthcare providers are one of barriers to legalized DNR orders. Also, more than half of participants were Sunni nurses and it shows that this problem may exist in other Sunni populations. In addition, this study shows that Iranian nurses are willing to learn more about different aspects of DNR orders and analyzing their responses to many items showed their misconception about DNR orders. So, it is important to provide appropriate continuing education programs about DNR or other ethical challenges for nurses and adding such courses in educational curriculums of Baccalaureate nursing students. According to the result, it is possible that the attitude of Iranian nurses about DNR orders changed by such education.

The results of this study have some limitations. Firstly, even though this study was conducted in two provinces of Iran it did not cover all parts of Iran. Secondly, only the attitude of nurses about the DNR orders investigated and their knowledge was not assessed. Thirdly, the practice of oral DNR decision not investigated in Iranian healthcare system. Therefore, it was recommended that in any future studies the knowledge of Iranian healthcare professionals about DNR orders and the practice of DNR orders should be investigated.

CONCLUSION

The results showed that Iranian nurses have negative attitudes towards DNR in many key items of attitudes of DNR questionnaire. There was no difference between attitude of nurses from two main sects of Islam, Shiite and Sunni, towards DNR orders. This study highlights that educating healthcare providers about DNR laws and religious aspects of DNR in Islam may change the attitudes of healthcare providers toward DNR orders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study is a result of a MS thesis submitted to Nursing and Midwifery faculty of TUOMS. The research deputy of TUOMS and Hematology and Oncology Research Center affiliated to TUOMS supported this project financially. Authors would like to appreciate all nurses who accepted to participate in present study.

Source of Support: This research conducted by financial support of research deputy of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and Hematology and Oncology Research Center affiliated to Tabriz University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and do-not-resuscitate orders: A guide for clinicians. Am J Med. 2010;123:4-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The “do not resuscitate” order; clinical and ethical rationale and implications. Med Law. 2000;19:623-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- In-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: Prearrest morbidity and outcome. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:845-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- EURELD Consortium. Do-not-resuscitate decisions in six European countries. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1686-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- What is the meaning of palliative care in the Asia-Pacific region? Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2010;6:197-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cultural and religious aspects of palliative care. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2011;1:154-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nurses’ attitudes toward do-not-resuscitate orders. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1998;19:538-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- To resuscitate or not: A dilemma in terminal cancer care. Resuscitation. 2001;49:289-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Decisions and attitudes of nurses caring for severely ill elderly patients: A culture-comparing study. Pflege. 1999;12:244-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Practices of anaesthesiologists with regard to withholding and withdrawal of life support from the critically ill in Turkey. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004;48:457-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physicians’ attitudes towards ‘do-not-resuscitate’orders for the elderly: A survey in Saudi Arabia. Arch Gerontol Geriat. 2000;30:151-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation preferences among health professionals in Singapore. Crit Care Shock. 2004;7:219-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- The terminally ill Muslim: Death and dying from the Muslim perspective. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2001;18:251-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes of medical personnel toward do-not-resuscitate orders. In: MS Dissertation. Long Beach: Department of Social Work, California State University; 2000.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intensive care unit of nurses’ attitudes toward euthanasia. Iranian J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2012;5:80-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nurses’ attitudes Tehran of Medical University hospitals towards euthanasia. Iranian J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2010;3:37-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes of interns Tehran University of medical sciences towards euthanasia. Iranian J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2009;3:43-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- An Islamic medical and legal prospective of do not resuscitate order in critical care medicine. Internet J Health. 2008;7:12-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- End of life ethical Issues and Islamic views. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;6:5-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer ethics from the Islamic point of view. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;6:17-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes of iranian interns and residents towards euthanasia. World Appl Sci J. 2010;8:486-9.

- [Google Scholar]